About the Author: Vinnie studied film and sociology in Brussels and Ghent. He writes about cinema and social issues. As a PWS himself, he started cataloguing films depicting PWS in film school. Recently, he started giving presentations and workshops on the subject. Calling for awareness considering the complex relation between cinema and public perception. About the Author: Vinnie studied film and sociology in Brussels and Ghent. He writes about cinema and social issues. As a PWS himself, he started cataloguing films depicting PWS in film school. Recently, he started giving presentations and workshops on the subject. Calling for awareness considering the complex relation between cinema and public perception. |

L: You talk so smooth… you have an answer for everything.

B: Whatcha want me to do. Learn how to do stutter?

-Dialogue from Casablanca (1942)

It is to be noted that this essay will discuss plot points from various movies. The movies discussed are found in the reference-list at the bottom.

Introduction: representation as empowerment

What we see on the screen is not reality. Cinema is a representation of reality, carefully constructed by a team of filmmakers, making it ‘larger than life’. Many instances exist where the world from the screen hopped over to the real world. Venice, in the minds of the public, has been nothing but shiny canals and gondoliers since Top Hat (1935). Ever since Jaws (1975), sharks terrify people. You never saw a Dinosaur, but if you want to imagine a living one, you will probably use Jurassic Park (1993) as a reference.

Many aspects of them cinema have since become part of the collective unconscious. Movies defined how we looked at romance and relationships. They helped us to visualise how war looks like. Most importantly they confronted us with people that may have traits we have never seen before. To tell a story, filmmakers must make sure that the story they tell is legible to the audience. They use cinematography to convey tone and emotion. However, making contents legible transgresses form and easily moves into the realm of content. Hence, popular entertainment often adds to the creation and spread of stereotypes. Film both takes from public perception and adds to it, creating a self-reinforcing loop. Essentially, film is a barometer of thoughts of the public. Most of the screenwriters and directors that use stuttering characters are not People Who Stutter (PWS) themselves. Not all of them take the time to explore such a complex condition. Yet, their way of presenting can make an illusion seem real in the minds of audiences. Portrayed consistently, as shy and offbeat, audiences might expect PWS to act similarly in real life. As Zaller (1992) demonstrates, individuals rarely have a pre-decided opinion on a subject. Rather, they sample individual considerations from the information they consume to form an opinion-on-the-spot. If a person has never met a PWS before, he is very likely to subconsciously fall back on the information that he knows. For example a certain scene in a movie where the PWS was handled in a certain way. As we will see, many films use stuttering to signal a flaw in character that is central to the plot.

This essay will discuss a sample of films to show underlying trends of cinematic representation of stuttering. By speaking up and attacking misconceptions, the public perception, as disseminated in films, could improve. A realistic view of PWS in cinema would allow PWS to see themselves more realistically. While it is of course never a bad idea to laugh with ourselves, a general call to awareness to avoid non-realistic portrayals and the spread of misinformation through cinema would help in informing the public about stuttering. Based on Cristobal’s (2009) notion of transfluency, where stuttering is considered an outing of human diversity rather than a deficit, it is important to chance public perception when it is inaccurate.

The sound of silence

Stuttering is more than the repetition or interruption of speech. It also involves facial expression and hidden feelings or thoughts. How fitting it is that the first stuttering character in cinema is Harold in Girl Shy (1924), a silent film. In this story, a shy writer tries to form relationships with women, while writing a book about forming relationships with women. Throughout the film, he is confronted with a variety of speech-related problematic situations. He fails to persuade his publisher, he misses a train when he tries to buy a ticket, and he does not want to dance afraid of someone mocking his speech.

Harold tries to order a ticket while the train is passing by.

A redeeming trait is the suggestion that Harold is more than his stutter. As we will see, many films use stuttering to signal a flaw in character. There is an interesting parallel between Harold’s current predicaments, the failure to connect to people, and the book that he is writing, about connection and interaction. It is suggested that Harold knows perfectly well how to interact in theory. However, his stutter messes up the moment. Albeit that the stutter is sometimes used as a gimmick (for example, Harold’s stutters are accompanied by a shaky violin), the overall portrayal is realistic.

After Harold’s character develops a relation with a girl, his fluency increases. If the relation starts going south, the fluency decreases. While this is realistic, the association between ‘love’ and ‘stuttering’ can be problematic. This advances the idea that PWS speak the way they do as associated with sexual frustration or general dissatisfaction. The increase in fluency is possible due to increased comfort but, in the minds of the audience, this can lead to some problematic associations. While Girl Shy is a noteworthy and nuanced film for its time, the overall thoughts that the film creates about stuttering do need some context.

Nina G (2019) joked that, a few decades ago, the closest thing to a role model for PWS was Porky Pig. Take, for example, The Case of the Stuttering Pig (1937). Porky Pig’s primary stuttering traits are severely exaggerated. Warner Bros stated that, in their cartoons, they wanted to give each of their characters a recognizable trait. Porky Pig’s happened to be stuttering. The studio hired Joe Dougherty, who stuttered, to voice Porky. However, Joe could not control his stutter, which lead to lengthened recording sessions. Warner Bros eventually fired Joe and replaced him. Mel used the stuttering to maximal comedic potential. In interviews, Mel stated that he did not really intend Porky’s voice as a stutter, but rather than the repetitive grunting of pigs. Due to upheaval considering Porky, Warner Bros donated 12.000 dollars to the National Stuttering Project (NSP) in San Francisco and made a series of public service announcements denouncing bullies.

Nina G (2019) joked that, a few decades ago, the closest thing to a role model for PWS was Porky Pig. Take, for example, The Case of the Stuttering Pig (1937). Porky Pig’s primary stuttering traits are severely exaggerated. Warner Bros stated that, in their cartoons, they wanted to give each of their characters a recognizable trait. Porky Pig’s happened to be stuttering. The studio hired Joe Dougherty, who stuttered, to voice Porky. However, Joe could not control his stutter, which lead to lengthened recording sessions. Warner Bros eventually fired Joe and replaced him. Mel used the stuttering to maximal comedic potential. In interviews, Mel stated that he did not really intend Porky’s voice as a stutter, but rather than the repetitive grunting of pigs. Due to upheaval considering Porky, Warner Bros donated 12.000 dollars to the National Stuttering Project (NSP) in San Francisco and made a series of public service announcements denouncing bullies.

With the coming of sound, the most well-known aspect of stuttering could now be used: interrupted speech. In the ‘70s, we start to notice different recurring ways of showing stuttering.

Stuttering as abnormal

Since fluency is more common than non-fluency, human communication has traditionally been dominated by the view of ableism (St. Pierre, 2012). Fluent speech is a ‘normal ability’. All deviance needs to be ‘corrected’ to conform to the norm.

In The Cowboys (1972) a young stuttering boy called Bob sees someone drowning. Panicking, he tries to call for Andersen, but has a severe block that almost leads to the death of the victim. Bob is then verbally abused and blamed for the possible death. He should quit stuttering or go away. Bob starts swearing at Andersen and loses his stutter in the progress. Bob ceases to not stutter. This idea, that a stutter is something to ‘snap out of’, is hurtful and unrealistic. It sees the stutter as a serious flaw to be rectified.

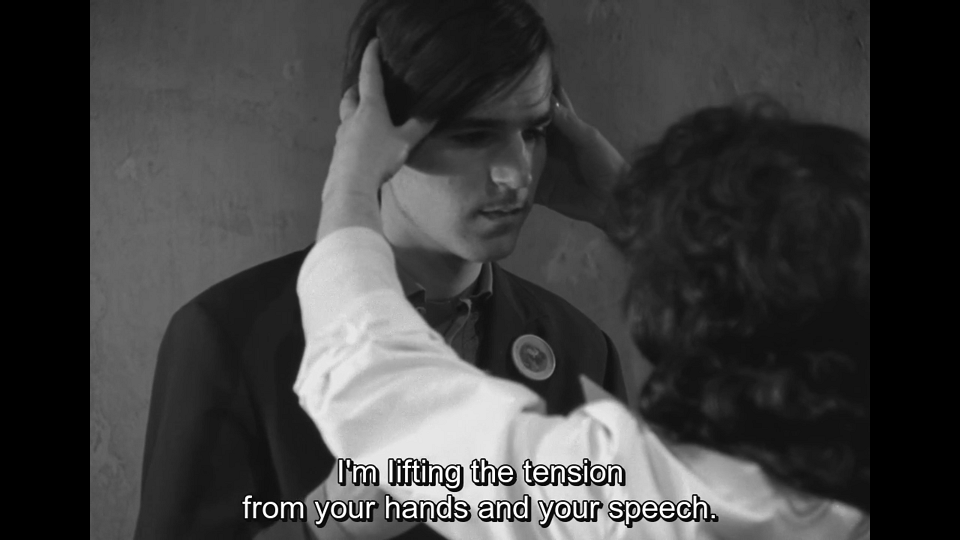

This idea of ‘stuttering to be rectified’ is commonplace. In One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), Billy is an inmate in a mental asylum. While the stutter is not the primary reason for his incarceration, his ‘problematic’ traits, like heavy nervousness and anxiety, are continuously associated with it. After having intercourse, his stutter vanishes, only to come back after nurse Ratchet scolds him and reminds him of his ‘mother’. Stuttering becomes associated with trauma. Once the trauma leaves, the stuttering leaves. Billy, unable to cope, finally commits suicide. In The Mirror (1975), Yuri Zhari is ‘cured’ from his stutter after hypnosis. A therapist asks Yuri to move all his tension to his hands. By removing the tension, the stutter also vanishes.

Yuri Zhari loses his stutter after hypnosis

Stating that stuttering needs to be rectified advances the idea that there is something inherently wrong with this manner of speech. Examples of this are widespread and notably related to ‘perceived innocence.’ For example in Harry Potter and The Philosopher’s Stone (2001). At the big finale, Professor Quirrell reveals that he only stuttered because no one would suspect ‘poor, stuttering professor Quirrell.’ Next to the sly Snape, the audience is tricked into believing that Snape is the villain, while using stuttering as a ploy to mislead the audience.

Who would suspect him?

In My Cousin Vinny (1992), stuttering is linked to ‘incompetence’. During several court case-scenes, a stuttering lawyer severely blocks, spits on members of the jury, and generally makes a fool of himself. At this point in the film, the stutter does not serve a purpose, apart from laughing at the lawyer’s incompetence and the surfacing doubts of the accused, who realises he will never get off with a stuttering lawyer. It is interesting that, when the lawyer starts his plea, he stutters less. He appears confident, only to lose it when unable to answer difficult questions, after which the stuttering resurfaces.

Pain and humour

Comedy and drama are inevitably interlinked. Every great comedy has the slightest hint of sadness. Stuttering is then used in different registers: sometimes for a laugh, sometimes for a cry, most often a combination. While there is no shortage of stuttering characters used as comic relief, this is not as commonplace as one would think. In Life of Brian (1979), the stutter creates frustration with other characters, only to reveal that the stutterer did not stutter at all.

The most interesting example is A Fish Called Wanda (1988). Michael Palin, whose father stutters and also created ‘The Michael Palin Centre For Stammering Children’, plays Ken Pile. Early in the film, he is confronted with Otto West, a severe bully who mocks Ken. Observe Otto’s reaction to Ken’s stutter. It is an example of what is commonly referred to as ‘The Face’: people being taken aback by a stutter. Nevertheless, a fish called Wanda is actually an interesting film concerning stuttering. While Otto does bully Ken, by for example finishing sentences or imitation, it is revealed that he uses the defects of others to mask his own.

The Face: stills from A Fish Called Wanda (left) and My Cousin Vinny (right)

Conclusion: the advent of positivity

While the international stuttering community advocates for awareness and a more positive view of stuttering, cinema is not always on board with that ideal. Different examples of (problematic) portrayals have been shown, which show stuttering characters to be untrustworthy, incompetent or annoying. While cinema is not reality, these stereotypes can spread and hurt PWS. Luckily, in the last decade we have seen some examples of positive portrayal.

Most films use stuttering to signal a flaw in character, but some exceptions use it to signal strength. In The Waterboy (1999) a shy, isolated boy uses his frustrations, originating from interrupted speech, to strengthen himself on the football field. By finding confidence and growing as a person, he becomes the star of the film. Similarly, in The King’s Speech (2010), we see King George VI struggling with his speech, only to transcend it. David Seidler, the screenwriter, stuttered. It was not a story about a character to whom the stuttering was added in for plot reasons, but a story about someone whose stutter has been with him his whole life. Someone who would prefer the real war of the day above his own personal one. When George watches Hitler’s speech, his daughter asks: ‘Dad, what does he say?’ To which George replies: ‘I don’t know, but he says it rather well.’ A fitting argument for the case that good speakers do not necessarily make good people. Confronted with such a well-spoken rival, George does not only manage to become a voice of the nation, but also a ‘symbol of nation resistance.’

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019) showed protagonist Rick Dalton with a slight stutter. There is no reason or hidden agenda for Rick having a stutter. It is just a natural part of him. In the same way that stuttering is a natural part of us.

Citations

Baudry, J., & Williams, A. (1974). Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus. Film Quarterly, 28(2), 39-47. doi:10.2307/1211632

Hargreaves, A., & McKinney, M. (2013). French cinema and post-colonial minorities. In Post-colonial cultures in France (pp. 75-99). Routledge.

Hall, S. (2001). Encoding/decoding. Media and cultural studies: Keyworks, 2.

Martiniello, M. (2015). Immigrants, ethnicized minorities and the arts: a relatively neglected research area. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 38(8), 1229-1235.

Nina G. (2019). Stutterer Interrupted: the comedian who almost didn’t happen. She writes press.

Zaller, J. R. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge university press.

Znaniecki, F. (1934). The method of sociology. New York: Farrar & Rinehart.

Cristobal, L. (2009, August 15). Towards a Notion of Transfluency. Retrieved from https://www.mnsu.edu/comdis/isad12/papers/loriente12.html

Films mentioned

Columbus C. (2001) Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone [Motion Picture]. United Kingdom: Warner Bros.

Crichton C. (1988) A Fish Called Wanda [Motion Picture]. United Kingdom: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Forman M. (1975) One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest [Motion Picture]. United States: Fantasy Films.

Hooper T. (2010) The King’s Speech [Motion Picture]. United Kingdom: See-Saw Films.

Jones T. (1979) Monty Python’s Life of Brian [Motion Picture]. United Kingdom: Python (Monty) Pictures.

Lynn J. (1992) My Cousin Vinny [Motion Picture]. United States: 20th Century Fox.

Newmeyer F. (1924) Girl Shy [Motion picture]. United States: The Harold Lloyd Corporation.

Rydell M. (1972) The Cowboys [Motion Picture]. United States: Warner Bros.

Sandrich, M. (1935) Top Hat [Motion picture]. United States: RKO.

Spielberg, S. (1975) Jaws [Motion picture]. United States: Universal.

Spielberg, S. (1993) Jurassic Park [Motion picture]. United States: Universal.

Tarantino Q. (2019) Once Upon A Time in … Hollywood [Motion Picture]. United States: Bona Film Group.

Tarkovsky A. (1975) Zerkalo [Motion Picture]. Soviet Union: Mosfilm.

Tashlin F. (1937) The Case of The Stuttering Pig [Cartoon]. United States: Warner Bros.

![]()

Super interesting and well written. I learned a lot. Also, nice picture Vinnie 😉

Never thought about stuttering being depicted in silent films! I’ll definitely check out Girl Shy. Thanks for the unintended recommendation 🙂

Wow! This was a fascinating and perceptive read. I vividly remember physically cringing when I saw My Cousin Vinny. I disliked it intensely, because it was using stuttering for a laugh but more so, I worried if that’s how I seemed portrayed by listeners in my own world. That was many years ago, before I began the journey of acceptance.

I honestly could not and did not watch some of the other films you noted, because I was afraid how I’d react and never wanted anyone to see me react in any way, thereby attaching my reaction to seeing and hearing stuttering on the screen, to me.

I went to see The Kings Speech by myself the first of 4 times I saw it, by then to desensitize myself to any reaction I’d have. I cried easily during the film and wasn’t embarrassed because I was alone. Then I was shocked when my mother and sister asked if I would go with to see it – the first time a family member ever connected me to stuttering. I remember sitting there choking on my sobs to contain them and I’d feel my mom and sister glance over at me, as though seeking permission from for them to react.

So this paper made me reflect, think and remember all the built up shame I carried around for so long whenever I was with somebody and we saw stuttering portrayed on screen. Finally, I can watch some things and not feel intense personal embarrassment.

This is truly a magnificent paper: so important to critically analyze the WHY each stuttering character is portrayed as such.

I am waiting for the day stuttering on screen is portrayed by an actor who really stutters and it’s not the main theme of the show, but rather as you note, someone neurodiverse who happens to stutter and just gets on with his life.

Thank you again for this great contribution.

Pam

At the world conference in Iceland there was a presentation by Erik Lamens about the same subject. Erik started a project to review movies with PWS, to see how the stuttering is depicted in the movie. The project put together a list of more than 500 (!) of such movies.

If you would like to review movies with a stuttering PWS, please contact StuttMov@gmail.com.

This article is very insightful and so powerful to read. You are right, unfortunately cinema does perpetuate stereotypes of people who stutter. Movies and media do not normally show the true depth of the stuttering experience, as a result the public is misinformed. I agree with you, the King’s Speech was a great representation. This movie was so well done, the actor playing King George seemed to portray stuttering well. My favorite part of the movie was the King’s final speech; he stuttered proudly. His speech was an excellent representation of their being no cure to stuttering, this is often lost in media. In the end the King was even able to joke about his stuttering, “I had to throw in a few so they knew it was me”.

Vinnie. This is an interesting and well researched presentation. Have learnt a lot from it.

Hi Vinnie. I truly enjoyed reading your piece as it was very informative. While reading your paper, I was quickly looking up clips to the corresponding movies- and I have to say, many of these were not easy to watch. I can understand Pamela’s experience and commend her for sharing. As a PWS and a person who analyzes many of these type of films, have you become somewhat desensitized? How did you react watching some of these movies for first time?

All the best!

Melani

I never really felt overtly emotional while watching these films. Like I said in the introduction, you don’t really watch PWS on screen, you watch someone else’s interpretation of a PWS. So no matter how wrong or ridiculous it is, I never feel affected by them. In a strange, paradoxal way, since I’m a PWS myself, PWS on-screen never feel real. I could probably empathize better with other characters with different traits if I don’t know anything about those traits. Whenever I see a PWS, my brain just flips into analytical mode like ‘oh, they used a PWS for some reason, let’s see what that reason is and how wrong they are.’

Hi Vinnie,

Thank you for sharing this thoughtful analysis! We clearly have a long way to go in terms of diverse (and realistic!) representations of communication and speech in the media. It seems that lack of representation in film has drawn more attention in the past few years. For example, we’ve seen a lot of push-back when white actors accept roles that portray characters of ethnicities and races other than their own.

What do you think about actors who do not stutter playing characters who stutter? When, if at all, is this appropriate?

Acting is about adopting a character. So I don’t feel it to be necessary that a PWS-character must be played by a PWS-actor. What is important, however, is research. We need more well-written PWS-characters played by actors who will do the research. Colin Firth in The King’s Speech or Leonardo DiCaprio in Once Upon A Time In … Hollywood are excellent examples of this. Neither of them stutters, yet their portrayal is honest and correct.

I am currently a graduate student studying speech-language pathology. We were given an assignment to evaluate a film and discuss the media’s portrayal of stuttering. I chose to evaluate The King’s Speech (2010). One scene from the film that stood out to me was Prince Albert expressing his concerns before his upcoming inauguration. The political tension was increasing between Germany and WWII was becoming more imminent. He disclosed, “The nation believes I speak for them, but I can’t speak.” I relate this back to the scene you mentioned: “When George watches Hitler’s speech, his daughter asks: ‘Dad, what does he say?’ To which George replies: ‘I don’t know, but he says it rather well.” The film facilitated a historical account of a public figure navigating his life with a fluency disorder. Typically, characters who stutter are portrayed as secondary characters, not the protagonist that is sympathized with and championed for. Films such as The Kings Speech (2011), increase the awareness of fluency disorders and decrease associated stigmas.

While I have seen some of these films, I was surprised to see how many more there were and how often they depicted people who stutter as a point of comedy or incompetence. Do you think that cinema will continue to lessen their depiction of such harsh stereotypes as they have more recently, or do you think that it will continue to be a problem for as long as we have such dramatized media?

It will always be a problem I think. To put it bluntly, some of these issues arise from bad writing with stereotypical characters. Even if we promote a correct and more holistic view of stuttering, some screenwriters and directors will slip through the net and show terrible portrayals of PWS. What worries me is not so much that there are films with such portrayals but that the portrayals showcase an underlying trend. So the ‘problem’ can’t be completely solved, but there is much ground to win here. Ideally, stuttering as a trait signalling incompetence or something else will be less common and more of an exception as stuttering is better understood by society, which will lead to a better understanding in film.

Thank you for this insightful read! I feel strongly about this topic because Hollywood should be more cautious on how they portray PWS in cinema. I feel as if some movies do display negative portrayals on stuttering. However, I should watch the King’s Speech (2011) since it is a top favorite. Before developing a movie based on PWS, directors, screenwriters, actors should thoroughly research and educate themselves on the characteristics (secondary characteristics), and emotional affects stuttering have on an individual. That way, they can have a better understanding an a more accurate portrayal on PWS through movies.

Thank you for such a informative article. It is interesting to learn about the earlier films you mention and even some background information you provided for the casting of these actors who did/did not stutter.

This article lead me to think about the young actor from the recent movie, Stephen King’s It. The role of Bill is played by Jaeden Lieberher. Bill’s stutter seemed fairly natural and a part of his character rather than what defines his character. It was stated that Jaeden spent more time independently researching stuttering and ways to stutter to perfect his role. Was curious if you had seen this film and your thoughts on their portrayal of stuttering. In addition, would you have any suggestions to on how actors should prepare for these types of roles to help accurately portray pws?

I have not yet seen It (shame on me!). But from what I’ve heard of it, it sounds similar to once upon a time in … Hollywood where there is no real ‘reason’ for the stutter. Which is, as I’ve tried to show in this article, the best way to go about things. Stuttering as a simple outing of diversity, not as a cheap joke.

As for research, I don’t believe in a set-in-stone path. There is no such thing as ‘THE PWS’. The last thing I want, is to have some sort of ‘common denominator PWS’-ideal to be constantly represented. So I place my confidence in the skills of actors to place stuttering in a more holistic frame. It influences a character, but it does not define it. Research into stuttering is good, but don’t let it turn into a set script with a series of checkboxes that need ticking off in order to ‘accurately represent stuttering’. It is all much more complex and nuanced than that. That’s why I like subtle acting. No ‘look at me, I’m stuttering!’. But organic, timid, … , as close to life as possible.

Thank you for this informative read! The field of cinema informs its viewers and allows its viewers to form their own conclusions or opinions on the characters. It is important to note how these characters are protrayed when films use stuttering as most viewers may think that PWS will act similarly in real life. Some producers use stuttering to show flaws in the character while others use it to show an overwhelming strength. I thought it was very interesting to learn about early films and the background information about the cast themselves and whether they actually stutter. In my fluency class in graduate school, my class has watched and analyzed films to view the stuttering, how to character is portrayed, and how he or she is treated for stuttering. It is important for producers, writers, and actors be informed and knowledgable about stuttering in order to portray it accurately because it could affect the viewers opinions of PWS.

Hi Vinnie!

This piece was very informative and a great read. I think that cinema and media has a long way to go in portraying accurate representations of PWS. You mention cinema using stuttering in a character to either show flaw or strength, and while showing strength is important I also think it is important formed to incorporate characters who stutter and its just that and not as something to advance the plot in any way. It seems that a lot of the inaccurate portrayals stem from the stereotypes of PWS that permeate popular culture. It is so important that we do better in accurately portraying these characters with better writing and more research.

Hi Vinnie,

This was a very interesting read. I hadn’t considered the negative stereotypes portrayed of PWS in film and how it affects those who deal with it daily. It’s insulting and invalidating to portray those who have a stutter as incompetent or incapacitated, especially for comedic effect. Bringing up Professor Quirell from Harry Potter was extremely interesting to me because I grew up loving those films and books, but to look back on it now, making him have a fake stutter for the reason they did was pretty problematic. One of my favorite films, however, happens to be The Kings Speech and is part of what piqued my interest in speech therapy in the first place, so I am very glad you included it in your conclusion. In what ways would you like to see PWS portrayed on screen and would you prefer actors who have real stutters to portray these characters?

This was a really interesting read. One thing I’d like to know is whether representations of PWS in television is more progressive than their portrayal in movies. Typically television is slightly ahead in terms of positive representation, but I can’t really think of any characters who stutter.

I wonder about that too. There are a lot less stuttering characters in television. That could be because the amount of content in cinema is larger than in television, but you would expect some more variety in recent years. Interesting to think about.

This website has a small list: https://www.mnsu.edu/comdis/kuster/media/tv.html

Hi Vinnie,

This is was a particularly enjoyable read for me. I am someone who takes great interest in film, and though I haven’t seen all of the films mentioned in this essay, I appreciated the particular points you make about each film and the way it portrays its character(s) who stutter and how this portrayal impacts public perception of people who stutter. I think it’s quite important that people who stutter are represented in films to come in ways that are accurate and relatable to people who stutter and give people who do not stutter a better understanding of stuttering as something a person can do that does not make them a bad or unworthy communicator. I’m interested to know what you would think of Stephen King’s It remakes that came out in the past couple of years. Bill is depicted as shy but kind, and he endures quite a bit of bullying because of his stutter. Do you think this is helpful in the sense that it makes a viewer aware of how a person who stutters may be treated, or harmful in the sense that Bill’s main problem in the film besides It himself is that he stutters?

Thanks,

Kate

Hello Vinnie!

This is was very insightful paper. I remember going to a play as a little girl and seeing a character who stutters portrayed as the “funny character” because of the things they said and how they said it. I was also told that the person who played this character was someone who stuttered in real life and they took the role because they felt empowered by making people laugh. Do you think PWS should take these type of roles or does this aide negative stereotypes?

-Leanna

That is a tricky question. If the person himself felt empowered, than that’s his good right. Kudos to him/her for having the guts to step up on stage.

That being said, if the play is merely a mockery of superficial traits that are deemed to be funny just because they are ‘different’, than that is precisely the kind of cheap, poorly written jokes that I find damaging. There are a lot of good jokes to be made using a stutter (look at this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HpqNjLX_hTs&has_verified=1), but simply using the weirdness of a stutter as a cheap platform is not okay in my regard.

Hi Vinnie!

Thank you for your response, I absolutely agree!

-Leanna