About the Author: Sanjeeva Murthy has a doctorate in Materials science and is currently a faculty member at Rutgers University. He is interested in speech disorders because he is a stutterer, and knows how a speech handicap can affect a person. He was born in India, and came to the United states as a student at the age of 22 in 1972. Everyone who knew him in India remembers him as someone who stutters. His stuttering almost disappeared the instant he landed in the U.S., perhaps because no one in the U.S. knew him, but it reappeared without warning on many occasions. He began to think about this intermittent stuttering and “normal” speech, and published a technical paper in 1980 describing his ideas in terms of a systems model (Integrated Analysis of Stuttering Using a Simple Conceptual Model. Folia phoniat, 1980. 32: p. 285-297). This ISAD article is based on ideas that are in that paper. |

Abstract

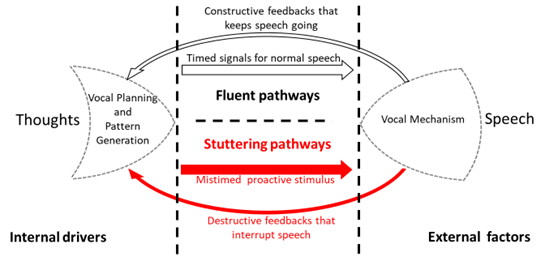

Stuttering is a hidden disability that requires a unique set of resources to manage in public. Classrooms being the biggest challenge for stutterers, awareness of stuttering and personalized support in schools would help stutters to be comfortable in their manner of speech and with the response of their listeners. To facilitate teachers and peers see and hear stuttering, I give a glimpse of what goes on inside a stutterer’s head using a simple schematic model. Stuttering is thought to be due to subtle differences in neural pathways to and from the vocal mechanism. The model emphasizes the role of the listeners and the environment that cause mis-timed proactive signals and trigger unwarranted feedback in the stutterer’s neural network that processes speech. Stutterers can achieve a semblance of fluency by circumventing some of these pathways using distraction to substitute anticipatory thoughts about stuttering. But this practice is unreliable. More robust remedies take advantage of the neuroplasticity by progressively substituting: (1) impaired feedback pathways with fluency-promoting feedback, and (2) proactive stimuli with constructive forward control. Psychological factors that contribute to stuttering can also manifest as personality traits that need to be addressed by the community around the stutterer.

Keywords: Stuttering. Anticipatory struggle. Feedback. Proactive stimulus. Neuroplasticity.

- Introduction

If a person is disfigured, blind or crippled, the disability is obvious and people’s response is predictable. The problem with stuttering is that it is hidden. Typical responses it elicits when it becomes visible make a stutterer shameful and embarrassed. It is not unusual that when a stutterer begins to speak, and the words don’t come out right, the positive impression that a new acquaintance or audience had about the stutterer quickly devolves into discomfort, tolerance, and even pity. Such occurrences repeated throughout a stutterer’s life determine his sociability, adversely affect relationships, scar the person, and determine his identity. Only other stutterers can fully appreciate its effect on one’s personality.

I used to think that my experiences as a stutterer were unique. By reading about other stutterers, I gradually realized that my experiences are not fundamentally different from those of other stutterers, just of a different shade. Yet, publicizing individual experiences would make stuttering visible to the public, benefitting stutterers, with each experience is in fact a case history for clinicians. My experience begins in childhood, being frustrated and angry at being not able to say my name, and to ask or answer a question in the class. Later, I felt helpless when I made people uncomfortable by my stuttering. I was always fearful of the consequences of stuttering. I consider myself now a borderline stutterer in which speech impediments strike without notice. Even at this late age in my 70’s, it is distressing not to be able to express one’s thoughts properly. Residuals of my life-long stuttering are obvious only to those who knew me till I was twentyish. Others think that I have an abnormal speech pattern because my speech is monotonous and labored, sounds unnatural with wrong intonations, is choppy with abrupt stops and starts. Occasionally, I show the classic stuttering characteristics such as part-word repetition, silent blocks and sound prolongation. Often, others in the room repeat exactly what I just said in a smooth, rhythmic and effortless delivery, and are more effective. With some level of controlled fluency that hides my stuttering, my speech is now tolerable. But I feel like an impostor, a stutterer masquerading as a fluent speaker.

Perception of the stutterers by the community and in the workplace can be normalized by educating the audience. This can be most effectively addressed in a school setting where a stutterer is often most seen and heard. More importantly, a stutterer experiences the most intense distress in classrooms. Awareness of stuttering in the community of teachers and peers may help a stutterer to cope better by stuttering without embarrassment, and even overcome it. While I was a child, my parents tried without success to treat my stuttering using faith healers and talismans. Growing up, I assumed that stuttering was a handicap that I just have to live with. As an adult, I realized that I could change how I speak by understanding stuttering. I describe my experiences here by weaving them into a schematic model.

- A systems model for stuttering

A model can be useful to explain stuttering to the public. Suppose a motor, such as the one in household air-handling systems, is instructed by a controller to open an air pathway. If the motor fails to respond, the control system senses this failure and resends the instruction. The motor is now caught between its inability to open because of the mechanical fault and the unceasing inputs from the controller to open. This tug-o-war between the expected outcome and the existing state resembles stuttering [1]. Following this analogy, speech can be thought of as being initiated by a hypothetical pattern generator in the brain that prepares a sequence of instructions for the vocal cords (left-third section in Figure 1), The right-third section represents the external factors including listeners that affect speech. The middle-third section represents the pathways that pass signals between the language processor and the vocal cord. Feedback loops are central to such models [2-7].

Figure 1. A schematic of the fluent (top half, open arrows) and stuttered (bottom half, filled arrows) speeches. Treatments are aimed at migration from one set of pathways to the other by taking advantage of neural plasticity.

2.1 Stuttering as impaired signaling pathways: We think faster than we speak. Stutterers, unlike fluent speakers, appear not able to manage this mismatch in speed. For me, words do not come out the way I see them. I have to consciously exert myself to hear my own words. [8]. A failure such as not being able to get word out, which does not perturb a fluent speaker in the least, causes destructive feedback that results in silence and pauses in a stutterer. This can be represented as an impairment of an unconscious feedback that modulates the speech, from the top open backward arrow in fluent speakers to the bottom filled backward arrow in stutterers. The impaired signal pathways are thought to be activated by anxiety. But I do not remember experiencing any moments of anxiety in my pre-teens while I stuttered away, including participating in debates, without considering how others would react to my stuttering. Only in my teens, I began to feel anxious about speaking and shied away from speaking. I devised ways to reduce my anxiety level to overcome stuttering. I began to substitute problem words to mask my handicap. In the words of Johnson [9], I just bumbled along, using techniques that seemed to work at that moment.

The filled forward arrow in Figure 1 represents the development of learned secondary behaviors in confirmed stutterers that exacerbate stuttering. This includes fear of certain words and situation, escape and avoidance, efforts to conceal the handicap by using starters, explaining the word, and by substitutions (circumlocution) that lead to bad syntax; sometimes what I said would be the exactly opposite of what I meant to say. The two stuttering pathways at the bottom of the figure represent the conflict during stuttering between urge to speak and not to speak [10, 11], the opposing forces in a tug-o-war [12], disagreement between the director and the actor in a play. My stuttering began to diminish once I realized that pathways that cause blockages and unconscious mental inhibition to affect fluency can be overcome.

My stuttering disappeared almost completely when I came to the U.S. when I was 21, where no one knew the old stuttering Me. But during my first visit to India after 4 years, I was taken aback to hear myself stutter as badly as before while talking to my family members and old friends as though mis-wired pathways remained waiting to be triggered by old memories. Even now, I stutter without being aware of it every time I talk to my old acquaintances and relatives who know me as a stutterer.

2.2 Proactive stimulus and failure to launch. Stuttering almost always occurs at the first syllable. This can be associated with an erroneously timed speech activation signal caused by a mismatch between the prediction and action. Ms. Lara Trump famously identified this when she mocked Mr. Joe Biden in the 2020 U.S. presidential race by saying “Joe, can you get it out? … Let’s get the words out, Joe.” [13]. When I was 10, I had to give my name to a teacher during registration in a school where they didn’t have my records. Because I couldn’t utter the first syllable my name, which used to be M.N. Sanjeeva Murthy, has become N. Sanjeeva Murthy. To avoid the difficulty with the opening syllable, I often used lead-ins, i.e., utter an unnecessary word prior to and in the same breath as the feared word.

Proactive stimulus from the brain, based on anticipated action of the vocal cord can explain this inability to start. An imposed rhythm, as it occurs during singing, can replace this stimulus and thus help some stutterers by preventing them from getting ahead of themselves. I was made aware of my lack of sense of timing while I was navigating a friend through busy Philadelphia streets before GPS era when my friend who was driving said, “you know Sanjeeva, you give me directions for the next turn and the one after it even before I am finished with this turn. It confuses me. Can you wait till I make the turn before you tell me what to do next?” I realized that is precisely what happens to me while speaking. It is as though the brain is pushing through a syllable through the vocal cord that is still executing the prior instruction. This is similar to the stuttering of the motor in the air-handling system discussed earlier.

- Mitigation of stuttering

Distraction, in essence, blocks the impaired pathways in Figure 1. Distraction can be brought about by thought substitution that relies on the left prefrontal cortex, or by direct suppression on the right. Chewing is most likely one of the earliest techniques devised to achieve distraction [14]. When I was about 7, I was asked to put a pebble in my mouth while speaking. This did not help; my stuttering got worse to such a degree I could not even say my name. In one stretch extending over months, I could not answer roll-call in my classes. One day during this period, I happened to crush my left thumb by a hammer, and was treated with iodine tincture. The next day, I happened to be smelling the iodine on my thumb when my name was called. To my and everybody’s surprise, I answered the roll call. This way, I discovered distraction as a means to avoid stuttering. Since my difficulty was always in starting a sentence, and because it got harder the more I thought, I tried not to think of the first syllable by distracting myself. I do not stutter in new situations such as speaking to a stranger at a bus stop, or in a critical situation such as angrily arguing with a landlord. Based on such experiences, I began to experiment by imagining or play-acting different scenarios, using a different tone, even pretending to be talking to child.

Distraction and forgetting being a stutterer can be expedient for achieving fluency, but is not reliable. The pathways in the middle-third of the diagram in Figure 1 suggest that fluency can be achieved by taking advantage of the neural plasticity [15]. Hypnosis probably works for the same reason [16]. As stutterers grow older, they learn to bypass the impaired pathways, every person finding a unique way to rewire the brain. Borrowing from the computer terminology, this is the equivalent of installing a new software to fix a problem, while issues with hardware (vocalization) and operating system (code preparation in neural networks) over which a stutterer has little control remain. Because of neural plasticity, stutter can be mitigated by speech therapist in children and by self-help in adults.

- Personality traits

Stuttering has conditioned my personality. It is also possible that my characteristic traits might have contributed to stuttering. It appears to me that a stutterer has a tendency to miss timing cues. This could be deep rooted in the brain, and be of genetic origin [17]. Thus, the behavior related to proactive stimulus or premature feedback could manifest in other activities as well, such as untypical haste, inability to wait for their turn to speak and restlessness. I have been faulted for not planning or looking ahead, not being in the moment, and not focused. A stutterer’s tug-o-war between whether to go ahead with a word or hold back is itself a sign of indecisiveness. While growing up, I was aware that people around me thought I behaved differently. Only in my 50’s I realized that my behavior has some characteristics of attention deficit disorders.

- Conclusions

Knowing that stuttering is often associated with anticipation, anxiety and avoidance, parents, teachers and peers can play an important role in helping a stutterer manage their stuttering. Stuttering can be thought of as mis-wired circuitry with malfunctioning pathways in the form of proactive stimulus and the speech-interrupting feedback. Distracting and making the stutterer forget that he is a stutterer can bypass these pathways, resulting in pretense of normal speech. Stuttering can be minimized by speaking slowly, reducing tension by proper breathing, maintaining proper eye contact to prevent avoidance, and by proper preparation to the point of rehearsing every sentence before it is uttered. Recognizing neural plasticity and acting on it provides a long-lasting solution. Many achieve fluency as they grow older; some for no obvious reasons, others because of conscious effort, or because of successful treatments. Treatments of stuttering need to be aimed at examining the personality traits and not just disorder in speech.

References

- Harrison, J.C., Redefining Stuttering: What the struggle to speak is really all about. 2011.

- Murthy, N.S., Integrated Analysis of Stuttering Using a Simple Conceptual Model. Folia phoniat, 1980. 32: p. 285-297.

- Civier, O., D. Bullock, L. Max, and F.H. Guenther, Computational modeling of stuttering caused by impairments in a basal ganglia thalamo-cortical circuit involved in syllable selection and initiation. Brain and language, 2013. 126(3): p. 263-278.

- Levelt, W.J.M., Producing spoken language: A blueprint of the speaker. InC. M. Brown & P. Hagoort (Eds.), The neurocognition of language (pp. 83–122). 1999, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Craig-McQuaide, A., H. Akram, L. Zrinzo, and E. Tripoliti, A review of brain circuitries involved in stuttering. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 2014. 8: p. 884.

- Hesse, T., Stuttering as a result of a misallocation of attention during speech. A theory. 2018. p. http://www.stuttering-theory.eu/AAT-2018e.pdf.

- Levelt, W.J.M., The ability to speak: From intentions to spoken words. European Review, 1995. 3(1): p. 13-23.

- Brown, S., R.J. Ingham, J.C. Ingham, A.R. Laird, and P.T. Fox, Stuttered and fluent speech production: an ALE meta‐analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Human brain mapping, 2005. 25(1): p. 105-117.

- Williams, D., Wendell Johnson and Charles Van Riper: A Remembrance of Them and Their Era. National Council on Stuttering 1999.

- Sheehan, J.G., Theory and treatment of stuttering as an approach-avoidance conflict. The Journal of Psychology, 1953. 36(1): p. 27-49.

- Sheehan, J.G. Conflict theory of stunering in J. Eiserson. in Stuttering: A Symposium. 1958.

- Harrison, J.C., Understanding the Speech Block. 2012. p. https://www.mnsu.edu/comdis/kuster/Infostuttering/Harrison/block.html.

- Sullenberger III, C.B., Like Joe Biden, I Once Stuttered, Too. I Dare You to Mock Me., in New York Times. 2020: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/18/opinion/sully-biden-stutter-lara-trump.html.

- Mohr, E., Chewing Therapy in Stuttering, in The Chewing Approach in Speech and Voice Therapy. 1951, Karger Publishers. p. 19-38.

- Guitar, B., Stuttering: An integrated approach to its nature and treatment. 2013: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Lovett, L.G., Stuttering and Anxiety Self Cures. 2016: Peace Love & Reason LLC.

17. Frigerio‐Domingues, C. and D. Drayna, Genetic contributions to stuttering: the current evidence. Molecular genetics & genomic medicine, 2017. 5(2): p. 95-102.

![]()

Hello, I wanted to thank you for your article. What I really liked about it is that you thoughtfully explained the mechanisms of stuttering while weaving your personal story. I think you have a gift for explaining complexities in an easy to understand manner. I’m really impressed that you were able to share nuanced parts of your journey, with such personal anecdotes. Thank you for enlightening me as I’m a CSUF student in a Fluency Disorders class hoping to learn and understand about the experiences of People who Stutter. Thank you.

@mary_lynn22: I appreciate you taking the time to say nice words about my article. In fact, I had in mind people like you when I began the article, and I am happy that it resonated with you. My intention was to tell students and clinicians dealing with speech disorders what goes on inside a stutterer so that you can help us and others cope with stuttering and other speech disorders. The current emphasis on communication through visual mediums and voice-activated phone messaging and other devices put so much burden on people who stutter. Thank you for reading my article.

So nice of you to take the time to answer. I’m happy that I was your target audience and found your article. Just now you mentioned the burden on the stutterer vis a vis communication through visual mediums. I think you may be speaking of Zoom, or something similar? You also mention voice activated phone messaging. I think part of my understanding as a future clinician is to consider these media and every aspect of a PWS’ life because honestly I hadn’t thought of that aspect. So once again, thank you for the enlightenement.

Yes. I was speaking of problems faced by stutterers during video conferencing. In the absence of body language, it is difficult to inject your self into the converstation because you can’t get words out at the right time. When you do, it is often too late. With voice-driven menus that banks, airlines and everybody else is now using, I often here the response “Sorry, I didn’t get that” when you are trying to get the word out.

That must be frustrating. I imagine experiencing numerous things like that throughout the day can be wearing.

Hello, I want to begin by saying I really enjoyed reading your article. I found it incredibly helpful seeing how you connected every area of stuttering with your personal experience and other known examples of stuttering. I am a student at CSUF majoring in communication sciences and disorders in a Fluency Disorders course. We have learned about secondary behaviors, and it was interesting seeing how you learned of them. One that caught my eye was when you were seven years old and realized distracting could make you avoid stuttering. Thank you for sharing your experience and sharing your knowledge!

Thank you for reading my piece. My hope people is that with shared experiences, peoople like you will help people speech disabilities overcome or deal with them.

Thank you for taking the time to answer. If there was one message you would like speech therapists to really understand about stuttering, what would it say?

My one message for a speech therapist treating a stutterer would be: Each stutterer is different. Unlike a pill that treats a whole class of physical ailments, there is no single modality of treatment for stuttering. Understanding the personality is as important as understanding the type of stuttering (not blocks, repetitions, prolongations etc. which are common, but the severity) for treating the stutterer.

Hello, my name is Genesis Melgar. After reading your insightful article, I began to reflect on my life and realized the situations in which I find myself most nervous and anxious are where I stutter most. I didn’t think of myself as a person with a stutter, but after reading this article, I realized I do some of those escape behaviors mentioned in the article. Especially in class. I hardly stuttered as a child, I just spoke extremely fast, and always thought about what to say next-the anticipation would drive me crazy.

However, getting to college, do you think my ‘anxiety’ and the competitive environment I find myself in, have contributed to my stutter? Your response would be greatly appreciated. Thank you for bringing awareness to this important issue that often gets neglected in classrooms.

HI Genesis,

Thank you for finding my article useful. First year of college was also the most stressful for me, and this also saw me stutter more. As I gained confidence with my abilities, and especially when my peers, who were all new to me, accepted me despite my stuttering, my stuttering began to decrease.

I think identifying the problems, which you seem to have done, is the most important step in finding a solution. Speaking fast is a behavior that something you can clearly modify. About “thought of what to say next”, I usually jot down the point I want to make by either jotting down either on a paper pad or make a mental note, before I start speaking. If I think I haven’t thought about how to say it, I usually don’t say it. Most of the things we say are not of any serious consequence.

I believe that you too will be able to speak well once you address the issues that makes you anxious. Living with the attitude that “this too will pass” might reduce the stress and anxiety. For people who speak fluently, speech just happens. For us, it is a performance. And it doesn’t have to be.

@nsmurthy

Thank you so much for your response. I really appreciate the thoughtful advice. I worry excessively about what to say next- but as you said, I should definitely frame precisely what I want to say before I say it.

I’ve tried to put this into practice these past few days, and I can happily say- I spoke at a slow place today at church! Which is another place I get so anxious! Thank you so much for your help! I look forward to reading more of your work.

Greetings Dr. Murthy. I want to likewise thank you for sharing life experiences as someone who stutters and for articulating the research behind stuttering in a way where someone like me, a student, would understand. I’m grateful.

A few elements of your roadmap stood out to me. First, the analogy of an air conditioning unit receiving signals from a controller to turn on was helpful; this, complemented by the model, gave me a visual to build off of.

Second, you mentioned how stress plays a significant role in stuttering, oftentimes at the onset, yet you describe not remembering your pre-teens as being particularly stressful. Do you consider this an anomaly?

Lastly, you talk about distraction as being an unreliable, yet helpful, tool to achieve fluency and then reference neural plasticity as a mode for mitigating a stutter. This concept still remains difficult to grasp for me. Are there any models or even research you’ve seen that would help me gain a better picture of what neural plasticity entails?

Once again, thanks for sharing.

@jmassip: Thank you for your positive comments. As I noted in another post, I was hoping that people like you would read this when I submitted this paper.

About why I didn’t feel stressed until I was in preteens: In my preteens, I was completely oblivious to other people’s feelings or I didn’t really care. Only when I began to pay attention to how others reacted to my speech and behavior, and I tried to be, i.e., speak, like others, that I felt inferior and got stressed out.

About distraction: I feel it is not promoted by speech language therapists because, as I say in the abstract, distraction is not a reliable. But it helps me even now. Malcom Fraser, founder of Stuttering Foundation of America, also talks about distraction as a tool (See 11th edition of his book “self-therapy for the stutterer”).

About plasticity: Biology is amazing. Our body is able to heal our wounds, reconnect severed nerves and fix our fractured bones without any external intervention. Our brain is even more astonishingly adaptable. It is able to find alternate pathways to circumvent problems. This is in fact main-stream research in Neuroscience (see Ref, 5 in my paper; also, see “How Stuttering Develops: The Multifactorial Dynamic Pathways Theory” by Anne Smitha and Christine Webera in Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research (2017). 60:2483–2505). Referring the diagram in the paper, by neural plasticity I mean the ability to switch from stuttering pathways in the bottom half of the scheme to the top half.

Hi Dr. Murthy,

Thank you so much for sharing your article. As a student currently studying stuttering, I find it very valuable to hear a scientific perspective that is also personal. Something that caught my attention was that you seemed to experience spontaneous recovery when you moved to the U.S, but later had your stutter return unexpectedly. You touched on that briefly, attributing it to being in a new environment where no one knew you. Do you think there are other factors that contributed to its sudden termination and regeneration? Thanks!

@rachengonslaves: I appreciate you reading my article. I would not call the absence of stuttering when I came to the U.S. as termination. It temporarily disappeared, but reoccured intermittently. But it was not any where near to be recognized as a stutterer. Three reasons: (1) The new environment (it was 1972; without internet and TV – yes, no TV in India back then, everything was new and strange to me) was a distraction. As I say in the article, I believe distraction can be a powerful but unreliable tool to stop stuttering. (2) Coming to U.S. for graduate work (it was not common in the 1970’s) raised my confidence that contributed to my improved speech. (3) Once I realized I that I was speaking with out stutter for extended periods, it reinforced my belief that I can speak without stuttering. But all this were transitory, and I would stutter at the most inopportune moments.

Sanjeeva

Hi Dr. Murthy,

I wanted to reach out and let you know that I enjoyed your article! I particularly found your personal experiences as someone who stutters to be very insightful, and I thank you for sharing. I am currently enrolled in a fluency disorders course at my university and am intrigued with the information you discussed (paying attention to personality traits in order to determine psychological factors of stuttering, utilizing neuroplasticity, distraction techniques, etc.).

As a student studying to become a Speech Pathologist, how would one implement neuroplasticity on a patient who stutters? What techniques would you recommend they utilize?

Thank you!

@madimatta

Hi Madimatta,

Your question hits the target: taking advantage of neuroplasticity to stop stuttering is the central point of my paper even though I failed to suggest any techniques or recipes. Here it is from someone who is not an expert in neuroscience.

There is ample evidence to show that human brain can rewire itself to go around damaged regions of the brain. I have seen people after brain surgery in which parts of the brain tissue were excised and thus unable to speak or walk, regain these functions by shear practice. If they can do it, I believed that a stutterer can do this too. I told myself that there are alternate pathways from my brain to my vocal mechanism that I can call upon, or that there are negative inputs into speech pathway that I have to block. By consciously doing this, I guess one can exploit neuroplasticity. It is like forming a new habit. At the risk of sounding like a preacher, belief that this can happen and persistent practice, are my suggestions.

Hello Dr. Murthy,

I am currently a graduate student studying Speech-Language Pathology.

I truly enjoyed reading your article and learning about stuttering from your point of view. I think it’s absolutely essential that students learn about the experience of stuttering from PWS in addition to the classroom objectives. I do have a question regarding affect and how it influences fluency. You briefly mentioned in the article that your personality has influenced your stuttering and vice versa. If a 4 year old child is being evaluated for a fluency disorder, how much influence would a sensitive temperament have on said child.

Thank you so much!

@Kayschwartz

Thank you for reading my article. Comments such as yours make me feel that my effort to write that article was worthwhile.

I will preface my answer your question (how much influence would a sensitive temperament have on a child with fluence disorder?) by saying that I am not a child psychologist, and my comments are based on my experience.

There is very little external influence can do to make a child stutter. As I write in the article, the big fat filled red arrow in the middle of the figure in my article represents learned behavior that causes stuttering. But the structural source of the thin feedback arrow at the bottom of my figure, and what you call as sensitive temperament, are present in the child.

I can remember how I felt when I was 4-year-old, which was about when my parents began asking for advice about my stuttering. Why did I stutter as a child? It had to be something WITHIN me. But I was not aware of my personality back then. I was not even aware that stuttering was an issue. It was in my teens that I became aware of my hurriedness and of my borderline ADHD (I did not know it was ADHD back then). Only decades later, I began to think that these tendencies contribute to my stuttering. Would the child you speak of have these tendencies, that can later manifest as destructive feedback loops that interrupts normal speech?

Hi Dr. Murthy,

I am a graduate student studying speech pathology. What are your personal experiences with interruptions and suggestions from others about stuttering? Would you agree that these suggestions are sound? For example “slow down” “take a breath and restart” etc.

Thanks for sharing!

I believe that there is no one cause for stuttering, and there is no single technique that helps stutterers. Taking a deep breath and restarting does work for me, some times. When the problem is getting the first syllable out, slowing down is of no use. I stutter the most when I am stressed and excited, and the least when I am relaxed. When I lecture, I have realized plenty of preparation leads to stutter-free delivery.

Hello Dr. Murthy

I really enjoyed reading your article and learning your point of view! I am currently in a fluency disorder course and we learned that pausing in between your sentences is helpful as well as purposely stuttering. I agree that stuttering can be minimized by speaking slowly and breathing. What are some techniques an SLP can use with working with people who stutter?

Thank you !!!

Michelle Enriquez

Hello Michelle,

Thank you for reading my article. As I said before in these posts, I was hoping that SLP students interested in stuttering treatment would read my paper.

To rephrase my response to @ covarrubiasmaira (10/21/2022), each stutterer is unique. An experienced speech therapists will tailor the treatment by taking into account the severity of the stutterer and the expectations. For many therapists and stutters, the objective is to stutter without embarrassment. That was not for me. I wanted to at least give the appearance that I speak fluently. I knew this was possible because I had seen people who spoke fluently and admitted that they were once terrible stutterers.

In my article I discuss some of the technique that worked for me. Distraction works for me even now. I try not to think of what I want to say. This is possible only if I have carefully prepared what I am going to before a class lecture or a presentation. As a side benefit, the confidence that derives from careful preparation reduces anxiety. Anything that reduced anxiety is most effective. Not being worried about the consequence of your speech is also effective. There are some mechanical steps that has also helped me. One of this is taking a deep breath and pausing to think through what I am going to say, even though a pause might appear to last forever. The other is pacing your speech to an internal metronome, like tapping your fingers.

Unfortunately, many of these all these are psychological tricks that are aimed to rewire the brain. If the stutterer is a child, you may have to ask the child to follow some exercises that indirectly achieves these goals. For an adult, the path I took namely understanding why stuttering occurs and how others have dealt with it will help.

Hi Dr. Murphy,

I enjoyed reading your article, as I am a current speech pathology grad student working with clients who stutter. The way you explained the speech feedback system and how it is impaired in stutterers was very helpful in understanding what goes on at the brain’s level. I have a few questions after reading about your experience. You mentioned that distractions during speech contexts mitigated your stuttering, is this evidence of neuroplasticity taking place? If so, do you think it would be beneficial to foster distraction in therapy, while it might not always occur in natural contexts outside clinic? Thank you in advance for your thoughts!

Hi Laurel,

Thank you for reading my article, and for giving me an opportunity to explain outside the 2000-word limit set by ISAD.

Short answer to your question: Yes, distraction could be construed as a means to take advantage of the neuroplasticity and gradually re-wire the brain. Every time a stutterer avoids stuttering, either by distraction or something else (pausing, slow breathing etc.), I believe that the brain is getting trained to find alternate pathways to avoid stuttering. Artificial Intelligence network are in fact trained this way. Once the brain is trained on these new pathways, then the stuttering pathways, which I show in the bottom half the figure in my article, will be forgotten. In this sense, “distraction therapy” along with other modes of reinforcing behaviors, can succeed. This is what I call neuroplasticity.

As a teenager with very bad stuttering (the sentence, “In one stretch” in my article should begin with the phrase “In my teens” so as not give the impression that I was 7 when I injured my thumb with a hammer), my self-confidence took a hit every time I failed to say “present” or “yes” during roll call. So, my discovery of distraction was a life saver. That day is still etched in my mind. Because on that day, I realized that if I tried, I could one day speak fluently.

Your point that distraction might not always occur in natural contexts is very valid one. Once, my thumb healed within week or so, with no more tincture of iodine to smell, I came up with other tricks that I could use like looking away at something, or pretending to be occupied with some activity, or imagining I was talking to someone else, to reduce my stuttering. Gradually, I realized that I was stuttering less and less. Starting in my 30’s (late 1970’s), when I started reading the stuttering literature, I began to understand this process in terms of re-wiring the brain, or neuroplasticity. I believe that speech therapy in the form training the stutterer to speak slowly, breathing exercises, asking the stutterer to prepare well enough before speaking assignments so as not to feel anxious, and other technique gradually erase the pathways that cause stuttering. Aids such as distraction may not be necessary once the new pathways are established. This will take time.

Some therapists ask a stutterer to accept stuttering and stutter comfortably by teaching different modes of stuttering such as prolongations and fighting through the block. Others encourage the use of devices such auditory feedbacks and electronic devices. But I think there is a segment of stutterer whom neuroplasticity can provide a pathway to fluency. Look at Scully, Biden, and many others that you can find with Google Search (Famous People Who Stutter | Stuttering Foundation: A Nonprofit Organization Helping Those Who Stutter (stutteringhelp.org).

Hi Dr. Murthy,

Thank you for an intriguing insight into your experience as a stutterer and the models that concretely describe this complex communication difference to others. I was most curious about your concept of distraction and your responses in the comments to others about distraction. In working with people who stutter for over 45 years, I have found there to be different forms of distraction: auditory distraction, which suppresses the auditory pathway and enables the speech motor pathway to activate with more coordination (such as with delayed audio feedback, choral reading, etc–what many therapists call “fluency enhancing” techniques and you mention in your response to Laurel,) cognitive distraction (acting, using an accent/different form of speaking so that you are in a different “role”,) and emotional distraction (thinking about something else, increasing screen time, isolating yourself rather than confronting difficult thoughts.) I have found that all forms of distraction do not create durable fluency and increase cognitive load.

Auditory distraction is temporary and needs constant manipulation of the signal to be effective. It also impacts connection with your communication partner and does not portray your authentic self. Cognitive distraction is also not sustainable because it can create more significant cognitive load to maintain, rather than just going ahead and stuttering. Emotional distraction does not allow us to learn to manage difficult thoughts and create emotional flexibility.

You state that speech therapy for children and support groups for adults can be helpful. I will propose that the right kind of speech therapy can be helpful for any age. Therapy that is individualized, client driven and manages all aspects of stuttering; speech motor, cognitive and emotional systems. I will also say that support is crucial at all ages. In my children support groups, when I see a child meet another child who stutters for the first time…it is a magical moment, a realization that they are not alone.

All this said, I am not a person who stutters. In spite of working with stutters in many settings over many years, I still don’t understand the real experience because I don’t experience it. We need people like you to help us understand that experience and I am so grateful for your paper. I also know that communication is a basic human need and sometimes you just need to do whatever you can to get your point across, to send your message, to connect with your listener.

Thank you!

Rita

Hi Rita,

I am truly flattered that an experienced professional like you took the time to read my article and share your knowledge and understanding in the context of what I had written.

I do agree that all forms of distraction do not create durable fluency, and might become a burden for the stutterer. I used, and still use, these as crutches. If the goal is to achieve some semblance of fluency, I believe that we should learn to let go of these crutches. This is why I believe in neuroplasticity.

Therapy at any age is indeed helpful, except for those who have completely overcome this handicap and don’t need it. Embarrassment of stuttering does not diminish with age. In my case, I simply think about the instances that I stuttered most recently, and try to see why it occurred.

Thank you for your comments, and for helping people speak better,

Sanjeeva

Thank you for the ISAD 2022 Team for organizing this exciting on-line conference, and for all the readers who had interesting questions and made constructive comments.

Sanjeeva Murthy