About the Authors:

|

|

|

|

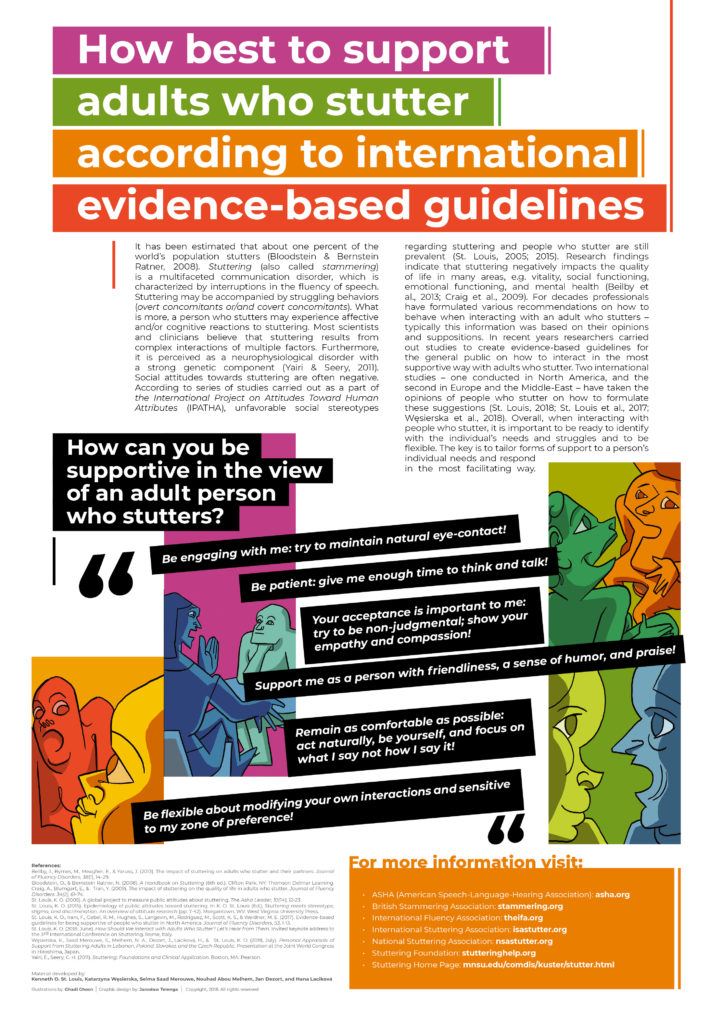

Our paper, describes the results of a multi-country survey of what adults who stutter have experienced and want to experience in the way of support by family, friends, colleagues, and others who do not stutter. The results are illustrated on a poster, could be translated from English into other languages, and offers convenient and broad dissemination. It encapsulates the common principles of interacting with people who stutter in the best way. This closely aligns with the theme of the conference, “Growth Through Speaking,” in that it educates the non-stuttering majority regarding how they might best interact with a stuttering individual. To this extent, the person who stutters will feel more comfortable with his or her stuttering.

Human beings are not able to survive in isolation; people are social creatures. The abilities to communicate, interact and participate are essential skills for humans. As we mature, we perform various social roles and discover our potential. We develop through communication. It stands to reason that communication as a fundamental human right and should be respected. Furthermore, all people, and no less people with disabilities, should have the right to freely communicate. The Universal Declaration of Communication Rights which was signed by almost 12,000 people proclaims: people with communication disabilities should have access to the support they need to realise their full potential (International Communication Project, 2014; Mulcair, Pietranton & Williams, 2018). This year’s theme of the International Stuttering Awareness Day (ISAD) online conference: Growth Through Speaking is an excellent extension of this idea. Indeed, Marcus Tullius Cicero, Roman statesman, orator and philosopher once said: We are born poets, we become orators. Similarly, Ralph Waldo Emerson asserted that all great speakers were bad speakers at first. Becoming a good speaker is a process and this is done primarily by practicing interpersonal communication in everyday life situations and by participating in interactions with others. As the readers of papers in this conference clearly recognize, some people who stutter seem incapable of interacting easily with others. Due to listeners’ uninformed or negative reactions, people who stutter cannot fully enjoy every day interpersonal communication activities, which can be overly challenging or even painful.

Research results reported from the International Project on Attitude Toward Human Attributes (IPATHA) show that negative social stereotypes are still very common among the public with regards to stuttering and to individuals who stutter (St. Louis, 2015). Public stereotypic beliefs have social consequences leading to internalization for the people who are stereotyped. Scientists have referred to this process in people who stutter as “self-stigma,” or negative beliefs, presumably derived from one’s family and society (Boyle & Blood, 2015). Behavioral components of attitude are also important. An overt pattern of behavior, or even the intention to act, can result in negative actions against a person or a group. These often take such forms as avoiding the person or group, aggression, or discrimination. What is interesting, people who stutter can be stigmatized not only by non-educated community members, but also by professionals. Ways that professionals stigmatize individuals who stutter include paternalism (“I know what is best for you.”), dependency (“You can’t live without me.”), marginalization (“I know parent training is important, but to be honest, it is just easier to work with kids myself.”), scapegoating (“It is your fault.”), or other forms of professional stigmatization (Downs, 2011).

Nevertheless, it has been the specialists, mainly speech-language pathologists, who have sought to educate the general public about how best to interact with people who stutter. Most professionals have long been convinced that most negative stereotyping, stigma and discrimination result from ignorance. Caring speech-language pathologists, especially those who were themselves people who stutter, have sought optimal approaches to educate family members, classmates, teachers, and general public about how to interact with people who stutter. As a result, numerous lists of DOs and DON’Ts for supporting children and adults who stutter have evolved. The rationale to create these lists was to help the non-stuttering majority be or become more educated, supportive, and helpful. The various lists and guidelines have been copied, translated, and widely disseminated; yet, their validity has not been supported with evidence.

To address this limitation, we sought to subject the advice typically given regarding interacting with people who stutter to evidence-based practice. One of the principles of evidence-based practice is to take into account clients’ needs, perspectives, beliefs, opinions, values, and goals in treatment (ASHA 2004; Kully & Langevin, 2005). St. Louis and colleagues surveyed people who stutter from the United States and Canada using a new instrument, the Personal Appraisal of Support for Stuttering–Adults inventory (PASS–Ad) with the purpose of developing evidence-based guidelines for the general public (St. Louis et al., 2017). The survey asked adults who stuttered to rate numerous of behaviors and beliefs according to how supportive they thought those would be for them. Additionally, the respondents were asked to rate those people in their lives who had, for them, been the most supportive. One year later, a replication study was conducted in Europe and the Middle East in order to extend the North American findings to samples of adults who stutter from four countries: Lebanon, Poland, Slovakia and the Czech Republic (St. Louis et al., 2019).

Overall, a significant majority of the respondents from both studies agreed with typical DOs and DON’Ts for interacting with people who stutter. The following conclusion, which was created as a summary of DOs and DON’Ts by St. Louis et al. (2017) characterized both studies:

When first interacting with a person who stutters in Western* societies, be engaging, patient, accepting, friendly, and as comfortable as possible, all the while being a good listener. After getting to know the person, learn more about stuttering and be flexible about modifying your interactions according the person’s personal preferences for being supported, realizing that sometimes a particular action, such as trying to guess and fill in a word being stuttered, though generally not advised, is sometimes desired. After considerable interaction, you may gently inquire if you should ask questions about the stuttering, offer advice or referrals, or otherwise comment on the stuttering, but be ready to respect the stuttering person’s wishes. (St. Louis et al., 2017, p. 10; 2019, p. 183).

*The term “Western” was substituted for “North American” after the replication (St. Louis et al., 2019).

As indicated, the primary purpose of these investigations was to develop evidence-based guidelines for interacting supportively with people who stutter by their communication partners. It was meant to revisit the traditional DOs and DON’Ts for interacting that have been widely publicized over the years from the perspective of people who stutter themselves. While collecting data for the second study, the European and Middle Eastern research team came up with the idea of creating an awareness poster that would summarize the main findings of the research in a graphical form.

The original version of the poster was created in English based on the collaborative work of the entire research team, consisting of the following people: Nouhad Abou Melhem (Lebanon), Jan Dezort (the Czech Republic), Hana Laciková (Slovakia), Selma Saad Merouwe (Lebanon), Katarzyna Węsierska (Poland), and Ken St. Louis (USA).

The illustrations added to the poster were created by the Lebanese artist Ghadi Ghosn. These illustrations of people who stutter captured in interactions with the other man could be perceived as quite harsh. Conversely, the poster team of creators agreed that the artist probably chose this way of expression to dramatize how stuttering can put a man in a difficult position during the process of communicating. The graphic design was prepared by the Polish graphic designer Jarosław Telenga. To date, the poster has been translated into Arabic, Czech, French, Polish, and Slovak. All language versions of the poster are available in open access on the website of the International Conference on Logopedics: Fluency Disorders: Theory and Practice: www.konferencja-zpm.edu.pl

The social model of disability has become increasingly widespread in recent years (Simpson, Everard, 2015). It promotes changing the perceptions and approaches of people struggling with different forms of disability. Whereas the medical model of disability projects that a disabled person must be cured rather than care for, the social model focuses on necessary social adjustments. According to the social model, among the key actions should be changing social attitudes towards disability and the disabled individual, especially providing appropriate social support. The social model requires society to disseminate knowledge about disability, increase understanding, nurture an accepting environment, and make appropriate accommodations for disabled individuals. The focus for applying the social model in the case of people who stutter should begin with removing barriers so that they can fully realize their potential, and indeed, to allow them to live their lives well, rather than to merely fix or repair them, as the medical model practices. Therefore, the perception of what leads to success in stuttering therapy and what its goals should be are reformulated. It was widely believed in the past that obtaining fluency was the most important manifestation of success in stuttering treatment. However, this point of view has been changing recently. More professionals have advocated that people who stutter should obtain the best possible communication skills and competencies for success in the different roles they’re expected to play in their daily lives. An interesting interview on this subject was granted by eight interviewees in an article entitled: Success in stuttering therapy – what is it and how to achieve it – opinions of ‘double’ experts (Blanchet et al., in press). These individuals were recognized as ‘double experts’ because of their everyday personal experiences with stuttering, while at the same time being professionally or socially engaged in outreach activities to support people who stutter. In the opinions of these double experts, the most vital sign of success in stuttering therapy is a person’s improved quality of life. This means, of course, that improving fluency can be one of the goals of therapy; however, also very important is to strengthen the process of change by building self-acceptance and by acknowledging a client’s readiness to face challenges. It is essential that individuals with stuttering be able to fulfill their goals, fully perform in daily life and actively participate in various forms of social activities. Only unrestricted communication can give such opportunities. What is more, for s person who stutters to be able to grow through speaking, some social changes must be addressed. No doubt, it is necessary to modify the unfavorable conditions currently present in society as much as we can. Some actions must be taken by both the stuttering community and specialists. A poster that disseminates evidence-based findings on improving appropriate interactions with people who stutter can be a helpful tool. It can be used to achieve significant changes in cultural competence during interactions with individuals who stutter in different social settings. The poster creators believe that summarizing the results of these multinational studies into one poster is a good example of utilizing evidence-based practice in stuttering advocacy and intervention. It can be used not only by professionals but also by people who stutter or self-help leaders so that they can spread the knowledge about how those who stutter would like to be treated when participating in daily life situations. In a few words and graphics, it can educate the public about the appropriate reactions and interactions with someone who stutters and about the fact that it is never too late to be supportive. We believe that this poster is one more way that people who stutter can apply this year’s ISAD theme, Growth Through Speaking.

The poster is copyrighted; however, the authors would be delighted to make it available in other languages. We welcome anyone wishing to translate the poster to another language to please arrange it with Katarzyna Wesierska beforehand. Please email her at: katarzyna.wesierska@us.edu.pl.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to thank their colleagues – all members of both research teams and all people involved in the poster creation.

References:

- ASHA (2004). Evidence-based practice in communication disorders: An Introduction [Technical Report], www.asha.org/policy.

- Blanchet, P., Boroń, A., Chmielewski G., Everard, R., Haase, T., Gładosz, Z., Jankowska-Szafarska, L., Ravid, B., St. Louis, K.O., & Węsierska, K. [in press]. Sukces w terapii jąkania – czym jest i jak go osiągnąć – opinie “podwójnych” ekspertów [Success in stuttering therapy – what is it and how to achieve it – opinions of ‘double’ experts]. In: K. Węsierska & M. Witkowski, (eds.), Zaburzenia płyności mowy – teoria i praktyka, tom 2 [Fluency Disorders: Theory and Practice, vol. 2]. Katowice, Poland: University of Silesia Publishing House.

- Boyle, M.P., & Blood, G.W. (2015). Stigma and stuttering. Conceptualizations, applications, and coping. In: K. O. St. Louis, (ed.), Stuttering meets stereotype, stigma, and discrimination. An overview of attitudes research, 43-70. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.

- Downs, D. (2011). How audiologists and speech-language pathologists can foster and combat stigma in people with communication disorders. In: R.J. Fourie (ed.), Therapeutic Process for communication disorders. A guide for clinicians and students, pp. 105-122. Hove, UK: Psychology Press.

- International Communication Project. (2014). Universal declaration of communication rights. Retrieved from: https://internationalcommunicationproject.com/profile/communication-basic-human-right/

- Kully, D., & Langevin, M. (2005). Evidence-based practice in fluency disorders. The ASHA Leader, October, 18, (23), 10–11.

- Mulcair, G., Pietranton, A.A., & Williams, C. (2018). The International Communication Project: Raising global awareness of communication as a human right. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 34-38.

- Simpson, S., & Everard., R. (2015, July). Stammering and the social model of disability: Implications for therapy. Paper presented to the International Fluency Association 8th World Congress on Fluency Disorders, Lisbon, Portugal.

- Louis, K. O. (2015). Epidemiology of Public Attitudes Toward Stuttering. In: K. O. St. Louis, (ed.), Stuttering meets stereotype, stigma, and discrimination. An overview of attitudes research, pp. 7-42. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.

- Louis, K. O., Irani, F., Gabel, R. M., Hughes, S., Langevin, M., Rodriguez, M., Scott, K. S., & Weidner, M. E. (2017). Evidence-based guidelines for being supportive of people who stutter in North America. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 53, 1-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jfludis.2017.05.002

- Louis, K.O., Węsierska, K, Saad Merouwe, S., Abou Melhem, N., Dezort, J., & Laciková, H., (2019). How should we interact with adults who stutter? Let’s hear from them. In: D. Tomaiuoli (Ed.), Proceedings of the 3nd International Conference on Stuttering, pp. 172-183. Trento: Erickson.

![]()

Katarzyna Węsierska is an assistant professor at the University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland and the founder and a speech-language therapist at the Logopedic Centre in Katowice. In her research and clinical practice, she focuses mainly on fluency disorders. She coordinates a self-help group for people who stutter and/or clutter at the University of Silesia. She is accredited by the Michael Palin Centre for Stammering in London to train Polish SLTs to use the Palin Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for Children. She cooperates with international organizations and researchers from different countries to disseminate knowledge and change social attitudes towards fluency disorders. Dr. Węsierska co-organizes the International Conference of Logopedics entitled Fluency Disorders: Theory and Practice at the University of Silesia. At the 11th Oxford Dysfluency Conference (2017, Oxford, UK) she was awarded the David Rowley Award for International Initiatives in Stuttering.

Katarzyna Węsierska is an assistant professor at the University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland and the founder and a speech-language therapist at the Logopedic Centre in Katowice. In her research and clinical practice, she focuses mainly on fluency disorders. She coordinates a self-help group for people who stutter and/or clutter at the University of Silesia. She is accredited by the Michael Palin Centre for Stammering in London to train Polish SLTs to use the Palin Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for Children. She cooperates with international organizations and researchers from different countries to disseminate knowledge and change social attitudes towards fluency disorders. Dr. Węsierska co-organizes the International Conference of Logopedics entitled Fluency Disorders: Theory and Practice at the University of Silesia. At the 11th Oxford Dysfluency Conference (2017, Oxford, UK) she was awarded the David Rowley Award for International Initiatives in Stuttering. Kenneth St. Louis is a professor emeritus of speech-language pathology in the Department of Communication Sciences & Disorders at West Virginia University. St. Louis has taught and treated fluency disorders, as well as a number of other communication disorders, for more than 40 years. His research has culminated in more than 150 publications and 300 presentations. He is an ASHA Fellow and was awarded the Deso Weiss Award for Excellence in Cluttering, WVU’s Benedum Distinguished Scholar Award, WVU’s Heebink Award for Outstanding Service to the State, and the International Fluency Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award. He founded the International Project of Attitudes Toward Human Attributes and has collaborated with numerous colleagues internationally on measuring public attitudes toward stuttering and other human attributes. Other current research and clinical interests include stories of stuttering, group therapy for stuttering, and the definition and symptomatology of cluttering.

Kenneth St. Louis is a professor emeritus of speech-language pathology in the Department of Communication Sciences & Disorders at West Virginia University. St. Louis has taught and treated fluency disorders, as well as a number of other communication disorders, for more than 40 years. His research has culminated in more than 150 publications and 300 presentations. He is an ASHA Fellow and was awarded the Deso Weiss Award for Excellence in Cluttering, WVU’s Benedum Distinguished Scholar Award, WVU’s Heebink Award for Outstanding Service to the State, and the International Fluency Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award. He founded the International Project of Attitudes Toward Human Attributes and has collaborated with numerous colleagues internationally on measuring public attitudes toward stuttering and other human attributes. Other current research and clinical interests include stories of stuttering, group therapy for stuttering, and the definition and symptomatology of cluttering.

Welcome to our article. I hope you find it useful.

Hi Kasia and Kenneth

Thank you for this very informative paper, and for the poster. The research you did is fascinating.

I am curious about the finding that “trying to guess and fill in a word being stuttered, though generally not advised, is sometimes desired.”. Can you give more information on what kind of data you gathered that supports this? I am not arguing that the statement is incorrect, but simply curious about how the statement was formed.

Before I learned about stuttering and that is it OK to stutter, there were a number of times when someone completed a word or sentence for me when I was stuck in block. I remember feeling both grateful for the help, and also hopelessness and shame. it was a fairly difficult emotional state to be in. I am wondering whether the data you gathered is correlated somehow to the place the PWS is in on the Journey to a place of Acceptance of their stutter.

Thanks a lot for making your research available to us. Thanks, also, for the detailed description of the social model of disability and it’s application to stuttering. It’s very helpful.

Hanan

Dear Hanan,

Thanks for the kind words and the question. The questionnaire asked respondents to rate each item as to how supportive it would be if a nonstuttering person acted in various ways. 1 = NOT SUPPORTIVE AT ALL; 5 = VERY SUPPORTIVE. You can see on this item, there was some difference. The Lebanese stutterers on average were “NEITHER SUPPORT OR LACK OF SUPPORT,” i.e., about 3 on the 1-5 scale. The other samples were in the “NOT SUPPORTIVE” range.

USA Lebanon Poland Slovakia Czech R. All

Try finish my stut wds 1.99 3.04 1.79 1.98 2.13 2.14

But all ratings were used. Here is the USA and the other 4-country data for this item in terms of percentages of respondents that used them:

1 2 3 4 5 ? n/a Omit Total

45% 29% 10% 9% 5% 1% 0% 1% 100%

50% 15% 12% 15% 8% 2% 0% 0% 100%

I agree that this might be an item that changes based on where an individual who stutters is on his/her journey toward acceptance.

I hope this clarifies.

Ken

Very interesting and useful article. Well done to all involved.

Thanks, Joseph! Kasia and Selma were primarily responsible.

Thank you for your kind words. I have an update about our poster. Thanks to efforts of Bornwell Katebe and Ernest Tembo the poster content has just been translated into the Bemba language (which is a language spoken in Zambia, Africa). The Bemba version of the poster will appear soon. In the same time, professor Norimune Kawai and his team from Japan are working on Japanese version of it.

Katarzyna & Kenneth (& Team)

My compliments to you all! The hard work that went into this is obvious. As a visual person, I appreciate how you have taken important pieces and translated it into a poster. I find it an inviting conversation piece between a person who stutters (pws) and their chosen communication partner. It invites the PWS to clarify their own personal preferences. (Recognizing this can change given their situation, feelings, etc.)

Thank you!

Erma Hanson

You’re welcome, Erma. This is just the kind of feedback we were hoping to get.

Ken

Katarzyna and Kenneth,

What a fantastic study! I really appreciate the evidence based practice aspect of this. While there is value in anecdotal and case study based information, the “do and don’t” lists based on this are not what we need to present to the family and friends and even others in the environs of a person who stutters. These posters are such a valuable resource to incorporate into practice with not only adults, but also children, in clinical settings as well as schools (preschool through college). As other commenters have mentioned, the personal preference of the person who stutters, which you specify on the poster, is the crucial component in support.

Thank you.

Regards,

Tabitha Syme

You are correct, Tabitha. One size does not fit all, as much as many of us would wish.

Thanks for the kind words. We agree that our Dos and Don’ts should be driven by what the recipients of those actions believe are supportive.

Hi Kasia and Kenneth,

Thank you for sharing your insightful article. The poster is a valuable resource that will be added to my “tool box” for future use. I am a graduate student currently taking a Stuttering evaluation and therapy course! After my peers and I discussed your paper, we wondered:

Is there a certain personality type/trait of people who stutter that is more commonly associated with wanting their conversational partners to try to guess/fill in a word being stuttered?

What is the best method to use when approaching a professional exhibiting unintentional or accidental stigmatization?

Best,

Esther, Katie, Caitlyn, and Erin

Esther, Katie, Caitlyn, and Erin,

Kasia has posted some excellent suggestions from Downs (2011). These are imperatives that even seasoned SLPs must continue to work on. All of us are capable of unintentional stigmatization. For evidence, simply read recent research on racism.

You asked about what personalities characterize stutterers who prefer others to fill in their stuttered words. Our studies did not have a personality component, so we cannot answer the question from our data. That said, it appears that stuttering individuals who are quite severe and who have not been either in therapy or in self help are less likely to reject a preference for others to fill in words for them. With insight that comes from sharing their stories of stuttering with others in safe environments, most adults and children who stutter come to the realization that what they have to say is worth waiting for.

Thanks for your post.

Ken

David Downs in his article (2011) suggested some strategies for professionals to combat stigma in people with communication disorders. Let me quote some of them:

“Combating paternalism

1. Encourage active participation of clients in all clinical areas: interview, evaluation, goal setting, treatment, termination, and follow up.

2. Respect decision-making of client event if you do not always agree with them.” (p. 111).

“Combating marginalization

1. Involve families of clients (that includes dads!) in evaluation, treatment, and follow-up even if it’s easier to do it yourself.

2. Talk to and, especially, listen to clients and their families interdisciplinary meetings.” (p. 114).

“Combating scapegoating

1. Admit you do not know when you do not know.

2. Take responsibility when you make mistakes.

3. Write clinical reports more in active voice.

4. Don’t imply parents of children with communication disorders are the sole determinants of their child’s progress.” (p. 115).

“Combating stereotyping

1. Do not assume simple solutions are sufficient to reduce stereotyping.

2. Use stigma simulations sparingly, if at all.

3. Have dealings with people with disability on an equal basis outside of the professional-client relationship” (p. 116).

Downs, D. (2011). How audiologists and speech-language pathologists can foster and combat stigma in people with communication disorders. In: R.J. Fourie (ed.), Therapeutic Process for communication disorders. A guide for clinicians and students, pp. 105-122. Hove, UK: Psychology Press.

Hi Kasia and Kenneth!

Thanks for sharing this informative paper, I was wondering if you had any specific tips for assessing or treating clients who stutter, I am a second year graduate student in Communication and Science Disorders and have not had much experience with this population.

Thanks !

Great article! I would love to have a copy of your poster. I work in the schools and I feel that this poster should be posted everywhere. Thanks again.

You’re welcome. Whew! A few tips? I’m not sure what I can say in a few words, but relative to our paper, it would be important to consider the implications of our poster in discussing stuttering with a child’s parents or a an adult client’s spouse or friends.

Good luck with your studies.

Ken

Sorry, this reply was meant for tianoamo.

Thanks. To get a poster, contact Katarzyna at the email address listed at the end of the paper.

Ken

Wow, what a great piece and collaborative effort. I think it is so important for people who stutter, professionals in the SLP field and other professionals to join forces and share best practices so that we are not constantly trying to recreate the wheel, but rather improve on it.

Visuals are always important reminders of what is socially acceptable and respectful for “the other 99%” to do when communicating and interacting with people who stutter.

This work reminds me of two documents created by the NSA, specifically for allies. They can be seen here https://westutter.org/wp-content/uploads/ally-2019.pdf

and here https://westutter.org/wp-content/uploads/medical-profesionals.pdf

So much more effort and outreach is needed to educate those who don’t stutter, who occupy the spaces we live, work and play in.

Thank you both for such a collaborative work and the message about the shift that some are seeing from medical model vs. social model.

There is so much to be gained from people with differences, aside from the world not being boring!

Pam

Thank you Pam!

Ken

Dear Kasia and Ken!

What an incredible work! I agree with you that your work fits very well with the topic of ISAD’s 2019 online-conference; Growth Through Speaking. I am so glad that you have collected so much informative and meaningful information, and that you are so willing to share the result with others. Thank you!

We need more data on this topic. Like you, I believe it is really important to collect more data from the perspective of the consumers (PWS in different age groups, parents, teachers, relevant others). I am grateful that you have been able to share and publish so much of the data already, and I am looking forward to follow your exciting research further into the future 🙂

Best wishes, and thank you again!

Hilda

Dear Hilda,

You are very welcome. We believe that the poster is a good way to summarize the information from the research.

We look forward to working with you on the next step of this effort. Perhaps a poster for supporting children especially will be forthcoming.

Kind regards,

Ken