About the authors:

People who stutter (PWS) typically expend a great deal of energy concealing their stuttering and avoid talking about their stuttering with others. This tendency to hide from stuttering creates a negative cycle of communication-related fears feeding more self-defeating avoidance behaviors and tense physical secondary behaviors.

Since we know that trying to avoid and conceal stuttering only fuels the problem, we attempt to reverse this process by encouraging PWS to be more open about their stuttering. This involves letting true, raw stuttering out, playing with different ways of stuttering voluntarily, educating strangers, friends, and family about stuttering, and self-disclosing stuttering in many different situations. We encourage our clients to communicate openly with their friends and family about their feelings and thoughts related to stuttering, and how they can be supportive. Clients are also encouraged to discuss aspects of their speech therapy, such as voluntary stuttering, desensitization, and self-advertising.

Many of our clients report that no one ever spoke about stuttering while they were growing up. Further, many claim that they are sure their friends know that they stutter even though they likewise have never discussed stuttering with them. Some people who travel to attend our intensive therapy programs tell us that they lied to friends and family about the reason for coming to New York. In our experience, those who are reluctant to speak about stuttering with others say they worry that it will be too uncomfortable to talk about it, that they fear what the other person might say, or worry that the other person will be dismissive or disinterested.

By completing activities such as the ones listed below, PWS experience that most people are in fact interested and supportive and that no one is nearly as bothered by stuttering as is the individual doing the stuttering! Our goal as clinicians is to help PWS modify the relationship they have with their stuttering. Many of the activities are designed to be fun and even competitive. As they complete the activities, PWS begin to shift their view of stuttering as awful and shameful to seeing it as a speech characteristic that while challenging, is nonetheless something they can accept and explore.

These are some of the specific activities we use at the American Institute for Stuttering. We engage in these activities in individual therapy, group therapy, and intensive programs. Many of these activities can be adapted for use with children.

Friends and Family Survey

“As part of my speech therapy I am working on talking more openly about my stuttering. Would you please answer these questions?”

- What do you think causes stuttering?

- What kinds of things do you think helps stuttering?

- What questions have you had about my stuttering or about stuttering in general?

- (We have clients write their own question here)

As part of the survey, the PWS has the chance to educate others, reinforcing what he or she is doing in therapy. We find that this activity sparks great conversations among family members and several of our clients have learned that they have other relatives who stutter that they didn’t know about!

Surveys with Strangers

“Hi, I’m ______________. I’m a person who stutters working on my speech. Would you mind taking a moment to answer a few questions about stuttering?”

- What do you think causes stuttering?

- What do you think a person who stutters could do to improve?

- Have you ever known anyone personally who stutters?

- (We have clients write their own question here)

Survey Experiment

“Do you know anyone personally who is a person who stutters?”

We have each member of a group predict what percentage of the general population personally will say they know a person who stutters. We then take a group of people out to collect as much data as they can and then see whose prediction comes closest.

Friends and Family Day

At the conclusion of our group intensive programs and sporadically throughout the year, we have group sessions where PWS are asked to invite friends and family members to our Clinic. The clients make speeches where they share about their personal journeys. We provide a “Stuttering 101” with basic information about stuttering and how loved ones can be supportive. We invite the visitors to write questions anonymously and we answer them as a group, sparking helpful discussions.

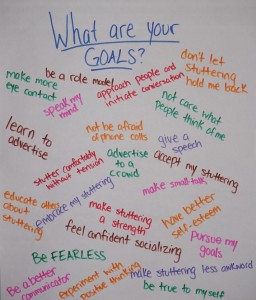

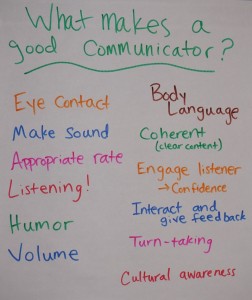

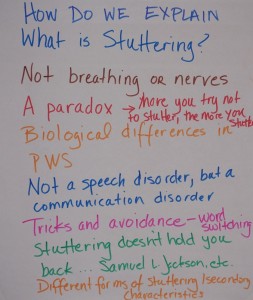

Throughout the intensive program, we work as a group creating posters that we then display on the walls. Examples include: visual depiction of stuttering iceberg, personal views on defining stuttering, ways to explain what stuttering is to others, personal goals for therapy, and aspects of effective communication. These written artifacts provide a great way for us to educate the clients’ friends and families about the specifics of their therapy, and gain more insight into the challenges of stuttering.

Here are some examples from recent groups (click on image to enlarge):

Education in the Park

“Hello, we are handing out some free information about stuttering.”

We create a postcard with a small list of interesting facts about stuttering and some Do’s and Don’ts for Listeners. We take groups out to parks to distribute the postcards.

Classroom Presentations for Children

“I’m going to say some statements about stuttering. For each one, raise your hand if you think it’s true.”

This provides a great way for CWS to self-disclose and become more comfortable about stuttering in school. We first work on creating the fact list in a session with the child. During the presentation, we hand out finger traps to educate the class about stuttering, show a short film, and the child leads the True/False activity.

Advertising phone calls and advertising in stores

“Hello, I have a question. I stutter so I may need a little extra time to speak.”

These activities have a strong desensitization effect; we find it helpful to have clients do a fairly large number of these in a row to experience the diminishment of anxious physical reactions.

Stuttering Scavenger Hunt

As a fun and challenging activity, we have small groups of clients compete to get as many points as possible in an hour by completing challenges such as educating street vendors, waiters, and salespeople about stuttering, advertising and asking random people questions, and using voluntary stuttering to ask for things they are trying to collect. We have the clients add challenges to the lists that they think will help them in their goal of becoming more fearless about stuttering and talking about stuttering openly.

![]()

These are excellent ideas. Thank you for sharing.

Our pleasure!

Growing up in a small elementary school there was a girl in my third grade classroom who never said anything in the classroom, but always got pulled out to go to speech therapy. When it was her turn to be star student of the week she created her poster and started out her presentation by saying, “I am afraid to give this presentation, because I stutter and do not know if you guys will be able to understand me.” Fourteen years later, I still remember her presentation like it was yesterday. After her star student presentation she started to participate more in the classroom and started to interact with everyone instead of being the quiet girl who sat in the corner. If it was not for her I would have never been told about stuttering going through my education until I got to college and declared a major in Communication Sciences and Disorders. As a future speech-language pathologist who wants to work in an educational setting, preferably elementary school, I really want to keep the activities you introduced in my mind, so that I am able to help the children I work with feel more comfortable about stuttering and informing their peers so that they feel comfortable communicating in the classroom and interacting outside of the classroom with their peers.

While reading about these activities I realized there are so many different ways a school or a community could host a program about stuttering, but in every city I have lived in I have never heard about a stuttering program taking place. Not only would a program about stutter raise awareness about stuttering, but it could also help community members who do not stutter change their view and be more accepting of people who do stutter.

As a graduate student of speech-language pathology, I was very intrigued by your article. The ideas you presented are great tools to educate our communities about stuttering while simultaneously instilling self-confidence in our clients to openly discuss their stuttering.

Your ideas are wonderful and have the potential for many positive outcomes including generating awareness, understanding and support from the general public as well as from family and friends. However, I was interested in hearing how you would prepare the client for the possibility of encountering a negative experience when performing one of these activities; for example, confronting a rude stranger who acts with indifference or impatience. How would you train a client to deal with such a possibility?

Hi Cheryl. We try to use “negative” reactions to our benefit by reframing our value judgment of things like having people walk away or say they don’t have time. We work to dispute thinking of these reactions as BAD- These are not “rejections” (as our clients first label them), the person simply couldn’t do the survey. With a little consideration, clients see that there are so many people doing surveys and the asking for money! in NYC and people often just say NO out of habit, some people are busy with they lunch or work, and others, we discover, don’t speak English. Clients generally tell us that even when interacting with “rude” people, they feel their courage grow and say the fear/anticipation was much greater than the discomfort of the actual interaction.

Hi, Heather and Carl. The ideas for exploring and accepting stuttering speech characteristic seem very helpful. I’ll be sure to implement some of the activities with my students. Sounds like you have a great program in NYC for persons who stutter.

Thanks. Lourdes

Thanks Lourdes!

Hello. I am a first year SLP graduate student. I have observed many people who stutter, and it is interesting to see their level of acceptance. One client in particular had a difficult time accepting her stutter and would become really emotional when talking about spreading the word. These activities would be really helpful to implement during therapy. Another aspect I learned this year is how important it is to educate the client on stuttering in general. I also love the education in the park idea to move the session out of the therapy room and advocate for people who stutter. Thank you for the great ideas!

Hello! I enjoyed reading this paper, and as a first-year SLP graduate student, I will consider these activities throughout my clinical experiences, so thank you for sharing your work! Throughout my studies, I have learned about and believe in the importance of the thoughts and feelings of a PWS for successful treatment. You stated in your paper that the goal as an SLP is to help the PWS change the relationship that he/she has with their stuttering, and that these activities will help to shift their view of stuttering from a negative perspective to a more positive and accepting perspective. My question is what if a PWS completes these activities and receives negative feedback specifically from their family members and friends, rather than from strangers? I know in one of your previous comments, you had explained the ways in which clients handle rude and negative experiences with strangers while performing these activities, but have you ever had any instances in which a family member or friend of a PWS responded negatively to these activities, and if so, how did you help the PWS to see the positive side of this situation? I can imagine that the impact of the views that families and friends of PWS have plays a huge role in the shift in a PWS’s view of his/her stuttering. Also, how do you equip your clients with responding to people’s answers that are false or incorrect. For instance, if a PWS asks someone “what do you think causes stuttering” and “what do you think a PWS could do to improve”, and that person responds with an answer that isn’t necessarily rude, but maybe is more of an absurd, illogical, or irrational answer, do you advise the PWS to inform that person of a more correct answer to that question?

Thank you for your ideas, help, and thoughts!

You bring up an important issue Teresa. For many of our clients, getting a supportive, positive conversation with family members is often very tough. We all know that some people have excessive conflict with family members, and if they stutter, the stuttering can become another point of contention. Every case is different, but sometimes it may indeed be preferable for some people to exclusively survey just select family members while deciding with others to “leave it alone” and choose not to. However, we do find that most of the time, when people have some reluctance to talk to family, thinking they will not be supportive, they come to see that there was more positivity than they anticipated. As for friends, we very rarely find that they react negatively. Of course, their answers to the survey questions, just as with strangers, are often incorrect. At that point, we absolutely encourage the client to educate and set them straight. That is one of the empowering elements of the experience.

Congratulations for the excellent work and thank you for sharing your experience with us. I would like to know from what age do you think these activities can be applied?

Daniela

Many of these are activities that we do with adults, but we often modify them for kids as well. In fact, for ISAD, we’re doing an event for teens and kids where we’re going to make t-shirts and then hand out flyers about stuttering at a local park here in NYC.

Are there any specific activities above that you’d like further ideas on how to modify for kids?

Hi Heather and Carl, I am a graduate student studying to be an SLP and enjoyed reading about all of your different suggestions to increase stuttering awareness! I think it is helpful and empowering for the person who stutters to be able to educate and discuss stuttering with others. I look forward to implementing these activities in my future practice. One question I have is if you have seen any trends in therapy outcomes in the individuals who use these activities? I am wondering if you think that these activities typically lend to greater fluency, self-confidence, less stress about stuttering, etc. Thank you!

Hi Lauren, Yes, we have definitely seen these activities help with confidence, speaking with greater ease, reducing fear and shame, etc… In fact, the reason we do these activities is for the client to make progress on those outcomes. Spreading awareness is nice bonus, but clinically, its not the primary objective.

Dr. Grossman and Mr. Herder,

Thank you for sharing these activities and offering your insight on how to help people who stutter speak with confidence and also how to ease their anxiety. As a future elementary school speech-language pathologist, I am certain that I will utilize the information shared in this paper.

I am currently in graduate school and I am taking a fluency disorders course. One of the requirements of this course was to participate in a pseudostuttering project in which I was required to stutter three different times, two of which had to be face-to- face with a stranger. During one of these experiences I pseudostuttered while ordering a pizza over the phone. Unfortunately, during this experience the worker did not wait for me to complete my order, but instead hung up on me. I bring this experience up as I relate it to the part of your paper in which the two of you address how a person who stutters should begin a phone call with an unfamiliar listener. I find it interesting how little strategies such as the latter can not only have positive impacts on the lives of those who stutter, but also how they spread awareness of stuttering to the public.

I’m glad you enjoyed our paper. Good luck as you start your career!

As a graduate student who is currently in a fluency course and who has had the opportunity to work with some PWS I found this information very insightful. I have seen first-hand as a student how concealing stuttering only fuels the problem. It was great to read how you encourage individuals to be more open about their stuttering. I also liked how as clinicians it is our goal to help PWS modify the relationship they have with their stuttering. The paper provided great activities that can help PWS shift their views of stuttering. I am looking forward to utilizing these activities in future therapeutic settings. Thank you for the great information.

It was our pleasure!

Hello,

Thank you so much for sharing. I am an SLP Graduate Student, who is also, currently in a fluency course. I have worked with various students in a local school district who stutter. I have also just today, experienced a day of pseudo-stuttering and using fluency techniques. I work at a high school and did my stuttering experience while at work. I can understand how self-advertising and desensitization are important. It was an exhausting day!

The activities and concepts you provided are excellent resources for those of who little experience under our belts. Thank you again for sharing! I will definitely use these activities in future therapy sessions.

Kendra S

SLP Graduate Student

Hi Kendra! Thanks for taking the time to read our paper. Since you’re working with kids who stutter in a school setting, you might benefit from reading our paper from last year’s conference, “Going beyond speech tools – alternative ideas for stuttering therapy”

Link – https://isad.live/isad-2014/papers-presented-by/therapy-research-and-other-fun-things/going-beyond-speech-tools-alternative-ideas-for-stuttering-therapy/

Hi! Thank you so much for sharing this article. I found every activity very creative and useful. I particularly found this work interesting due to the focus on educating as many people as possible. Before I chose a profession in this field I was not familiar with stuttering and the effects stuttering can have on a person. I am a first year graduate student studying fluency disorders. How does this individual and group intensive program differ from typical individual therapy and group therapy? Would you mind expanding on exactly the ways in which the program is considered intensive as opposed to traditional therapy?

Hi Heather and Carl,

I was attracted to your paper because my contribution to this year’s ISAD Conference is in a (somewhat) similar vein. We are, indeed, singing from the same hymn sheet. 🙂

I have long advocated the need to increase greater public awareness about stuttering. Can we really expect others to understand what is happening, or know how to react, when we suddenly block, display secondary behaviours, appear hesitant, or adopt a circumlocutory approach? In many instances, even members of our own families have little knowledge about the difficulties that we encounter.

That was the reason why, in 2001, I decided to do something about it. I felt it was time that other people should be acquainted with what it is like to be a person who stutters. Who better to explain such matters than those of us who have encountered such issues? As someone who had stuttered since early childhood, I reasoned that I was suitably qualified (and motivated) to contribute to the cause.

Having already sampled the benefits of speaking openly about stuttering (within my own environments), I recognised the potential value of discussing the subject in a much wider public arena. I also saw it as a means of challenging myself by speaking in situations that I had, invariably, avoided.

During the past 14 years, I have shared my story with several hundred community groups. I have been overwhelmed by the degree of interest generated by my talk. The response has been truly amazing.

Upon conclusion of each presentation, I conduct a Question and Answer session. Some enquiries relate to my own story, while others are of a general nature. My listeners also seek guidance as to how they should react in the presence of PWS. Many tell me that they were previously unaware of the extent to which stuttering can impact upon someone’s life. Having acquired a better understanding, they admit that they will now view stuttering in a different light.

I truly believe that the lives of many PWS could be significantly enhanced if more of us are prepared to speak publicly about the subject. However, I fully appreciate that the very nature of stuttering is such that some may well feel reluctant, or unable, to discuss it with others.

Those who are not yet ready to explore such uncharted waters alone, may gain confidence if accompanied by a relative, friend, member of the speech-language profession – or maybe another PWS?

Greater openness about my life-long communication issues has proved invaluable in helping me to overcome previous embarrassment. Revealing my ‘darkest secret’, to all and sundry, has greatly accelerated the desensitization process. My beliefs and perceptions (of what others think about me) are now extremely positive.

I have written (at greater length) about this subject in the following ISAD Conference paper:

“Increasing awareness and understanding of stuttering”

https://isad.live/isad-2015/papers-presented-by-2015/stories-and-experiences-with-stuttering-by-pws/increasing-awareness-and-understanding-of-stuttering/

I very much enjoyed reading your article.

Kindest regards

Alan Badmington

Heather and Carl,

Thank you so much for sharing! This was a great read and was very informative for me. As a graduate student in a speech-language pathology program, we are currently taking a fluency class. We haven’t yet covered treatment, but the tools you have presented will definitely be in my mind when we begin. It is so important to educate both fluent children and adults about stuttering so that they don’t see it as an excuse to humiliate someone but to rather help in some way – even if that way is simply understanding. I also think it is great that one of the main aims of the activities is to shift the way PWS view their stuttering. Thank you for sharing your knowledge, it will be put to use in future therapy!

Tayler

These are such great ideas! There is such variety that these activities can be used with a variety of clients who stutter depending on where the specific client is at.

Mr. Herder,

I am a former student of yours from when you taught a phonetics class at the University of Maryland. The world of speech-language pathology can seem so small! Good to hear from you and great to hear these suggestions. I’m a SLP graduate student now and love hearing ideas for group therapy. I really like “Family and Friends Day”. People shy away from uncomfortable situations, but I imagine people would be willing to talk about stuttering in a structured, relaxed, group activity. Thanks again!

Kristin Corman