Early on in my work with stuttering, I had a very clear “that didn’t work” moment with one of my clients. He wanted to overcome his difficulty with speaking on the phone, so we agreed to the age-old activity of calling local businesses and having brief conversations. By facing this feared activity, he would become desensitized to it, and the fear would subside. So the books had said…

Except, it didn’t work. With each phone call, his stress visibly increased. Blocks became longer and harder. After several calls, when I could practically hear his heart pounding from anxiety, I stopped him and said, “I don’t think this is helpful.” He agreed.

As a newly certified Speech and Languge Pathologist (SLP), this experience troubled me. I certainly understood why he would be anxious and why things would go this way, but I didn’t understand how to change this experience. I didn’t know how to help him, as his SLP. What was I missing here?

Theory to practice

Fortunately, I was introduced to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) at ASHA in 2013. ACT is a psychology and counseling framework that operates on the premise that life is uncomfortable, and rather than try to get rid of the discomfort, we should find a way to make it “workable” in our lives. Rather than changing the way I do therapy, this approach provided much-needed insight and perspective on therapy strategies that are already commonly used. Most importantly, the ACT principles have given me a new perspective regarding why challenging stuttering exercises might work, and how they can be used to even greater advantage.

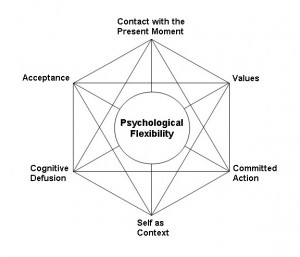

ACT has six core values that can be used as goal areas, and which work together to facilitate acceptance. The following paper explains what these six principles are, and how they might be applied therapeutically in a common voluntary stuttering exercise.

Experiential learning

I recently met with a client I’m going to call “Leah” for anonymity sake. Leah and I have been working together for a few months. Her overt stutter is borderline, or mild if she’s having a rough day, but how she sounds is a big deal to her. Stuttering, to Leah, is very negative. Our main goal in therapy is not to help her stutter less, but to help her reframe her experience of stuttering so that it becomes less negative.

Value 1: Present Moment

Many times, in my first voluntary stuttering exercise with someone, they don’t have to talk at all. I do all the talking (or, more accurately, stuttering), and I tell them to watch.

“OK, Leah,” I said. “I am going to ask all these people where the closest train stop is, and I’m going to stutter, a lot. I want you to watch the other person, and then tell me what happened afterwards. Observe my moment.”

Being in the present moment is a key core value of ACT. Life is made of moments. Some are uncomfortable, some are joyous, some are painful, some are exciting, some are multiple things all at the same time. All moments pass, though. A skill developed in ACT is the ability to be in a moment, acknowledge it, observe it, and then let it pass.

Being in the present moment is a key core value of ACT. Life is made of moments. Some are uncomfortable, some are joyous, some are painful, some are exciting, some are multiple things all at the same time. All moments pass, though. A skill developed in ACT is the ability to be in a moment, acknowledge it, observe it, and then let it pass.

With stuttering, the instinctive reflex is to get out of the moment as fast as possible. Panic mode, make it stop. Panic leads to the sensation of lost control and, more notably, lost perspective. It is very difficult to sit back and observe a moment when we are panicking.

Panic is an automatic response, and it’s pretty tough to actually obey the phrase “don’t panic”. I want Leah to see what is actually happening during a stuttering moment when she isn’t panicking. So, instead of making it her moment, I make it mine. Her job is to experience the moment of stuttering with the clarity of a panic-free experience. What might be different?

Value 2: Values

This value is one of my favorites, and works really nicely with other therapy approaches that focus on desensitization and reducing avoidance. Values is simply about identifying what is important to you, what you really want out of life. For stuttering, I often hear this stated as, “I want to say what I want to say, when I want to say it.” What prevents this from happening is not always the physical stutter itself. Most of the time, what prevents this value from being lived out is the fear of stuttering, or the fear of the consequences of stuttering. Fear leads to avoidance. In many therapy approaches, clients are challenged to reach for those things that they truly value, even if doing so is scary. This requires…

Value 3: Committed Action

In this session, I actually needed this value more than Leah. While not one of the six core values, this is another important principle in ACT: the therapist should experience and work towards goals along with the client, sharing struggles and fears.

Committed action happens after you’ve identified your values. “I want to say what I want to say, whenever I want to say it.” Then do that.

For this session, my value was that Leah be able to experience a moment of stuttering from a safe, non-panicking place. In order to do that, I was going to have to stutter a lot. This is not an easy thing, so it requires committed action.

A wonderful thing about therapy of any kind is the therapist-client relationship. This really helps with committed action. One, it is comforting to have a friendly person alongside when doing something challenging. Two, both the client and clinician can support each other during a challenging experience. I told Leah I was going to stutter, and so I had to.

This accountability partnership is key in the usual avoidance reduction activities when the client does the stuttering. The therapist challenges the client to voluntarily stutter during interactions. Often, I give people specific sentences to say, tell them to stutter on specific words, and even tell them how long they have to hold the block for. They’re scared, but committed. And they do the action.

Value 4: Self-as-context

This is always the trickiest ACT tenet to conceptualize, so I will quote Russ Harris, a chief author of ACT: the purpose of self-as-context is to “make contact with a sense of self that is a safe and consistent perspective from which to observe and accept all changing inner experiences.”[1] That still sounds a bit theoretical for the non-philosophically inclined, but I think it’s well-illustrated by the earlier panic example. Stuttering can easily be accompanied by panic. A PWS may lose their sense of self-as-context, and become completely wrapped up and defined by the stutter in that moment. They may fear that the listener will judge them by their stutter, because that’s all person who is stuttering is able to see, feel, hear, and sense in that moment.

Of course, the truth is that a stutter does not define a person. In fact, no single thing about a person can really define them. We are a mosaic of identities, beliefs, passions, relationships, joys, sorrows, experiences, memories, hopes, and goals. Working on self-as-context allows us to experience those parts that we don’t like so much (such as stuttering) while not losing perspective.

When I asked Leah to evaluate my interactions, she was very accurate. “He was really nice.” “She was kind of rushing you.” “She was pretty rude.” I’d generally agree, then say, “So, overall, how did you think that interaction went?” Every time, her answer was, “Well, you’re still here, so even if it didn’t go so well it’s not really a big deal.”

Now, I sometimes was not feeling so great during this voluntary stuttering exercise. I sometimes felt foolish, or angry, or annoyed at the people I had stuttered to, depending on their reaction. But, removed a safe distance from the experience, Leah was able to see the entire context. She saw that I made it through, that I’m in one piece, and able to move on to the next thing. The experience, the moment, was uncomfortable (present moment acknowledgment), but context helps keep things in perspective.

Value 5: Defusion

This is another of my favorite values. A common goal in ACT is “unstickying” oneself from negative thoughts, experiences, and identities. We can have them, acknowledge them, but we should not be fused with them.

I had a very personal experience with defusion during this exercise. The people I stuttered to today were an unusual bunch in that most of them actually reacted pretty negatively, which in turn made me become more self-conscious and panicky as I continued to stutter. After about five or six interactions, though, I had one listener whose reaction was so ridiculous that I nearly burst out laughing in the middle of my block (she obviously wasn’t intending to be ridiculous, so I managed to suppress it).

I asked Leah about it afterwards, and she agreed that it was bizarre. After discussing this strange response with someone else, I found myself defusing from the uncomfortable emotional experience I had attached, or “stickied” to it (to borrow an ACT phrase). This helped me reframe my thinking and separate from the discomfort and awkwardness experienced while stuttering.

Value 6: Acceptance

Acceptance. The holy grail of what so many modern therapy approaches strive for. Acceptance is complicated, though. It doesn’t mean that suddenly everything is perfect, and it doesn’t mean giving up or defeat.

Michael J. Fox’s take on acceptance very much echoes the principles of ACT: “Acceptance doesn’t mean resignation; it means understand that something is what it is and that there’s got to be a way through it.” Workability is a key concept in ACT, and facilitates acceptance. You can have something frustrating, uncomfortable, non-ideal be present in your life, as long as you can find a way to make it workable and live out your values.

I asked Leah what she thought about our interactions at the end of the session. “I thought it was helpful. I think I’m a little less scared now to stutter, this helped me see that life goes on. I still don’t want to stutter, and I don’t like stuttering, but I think I feel like things will be OK a bit more, now.”

Acceptance is a process, and Leah isn’t there yet. But that’s OK– as her therapist, I need to accept that it takes time for people to reach their goals, even if in my perfect world everyone would reach Zen nirvana after day one. Next time, Leah will do the stuttering, and I’ll watch her. She’ll have her own moments, and see what that experience has to teach her about herself.

Putting it all together

Blessed are the flexible, for they shall not be bent out of shape. — Anonymous

Despite its name, “acceptance” is not the goal of ACT. The goal of ACT is emotional flexibility: the ability to experience, move through, and live fully with the complex variety of human emotions, both the comfortable and the uncomfortable.

The most difficult speech therapy exercises can be the most liberating and life-changing. But, sometimes the task seems so large and painful that it’s hard to see the reward on the other side. Rather than “desensitize” to the discomfort and effort required, ACT validates that “Yep, this is hard. It’s going to feel hard, and be very uncomfortable. But there is another experience waiting that makes this worth it.”

Stuttering is hard. Even when a person has come to a place of “acceptance”, there can still be moments of pain, frustration, or disappointment. Acceptance doesn’t mean eliminating the possibility of ever reacting negatively to stuttering ever again. It means sometimes you’re down, and sometimes you’re up. But through it all, you’re living life: a full life, rich with values and action.

“You can’t stop the waves, but you can learn to surf.”

References

[1] Harris, Russ. (2009). ACT made simple. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

![]()

Dear Katie,

HI! It is so great to hear that more and more people are using ACT and applying it to PWS. Thank you for sharing your experiences with this approach with the world. I wish you continued success and kindness with your practice (and with yoga, board gaming! great hobbies).

Thank you for being an advocate for PWS and our field!

With compassion and kindness,

Scott

Thank you Scott! It was the short course presented by you and Janet at ASHA in ’13 that I have to thank for the introduction. I’ve enjoyed reading your continued writings on the topic, and it’s been great to see the approach disseminated more and more around our field. I’m looking forward to your upcoming presentation at ASHA!

Katie,

The wonderful thing about ACT is that it is free to anyone. The more you practice it, and more you try and choose to use it as a life style, the more it makes sense and the more it can be applied to many aspects of life.

I look forward to meeting you at ASHA! Keep being the person you are, and the person you strive to be. I love talking about this stuff with people who know ACT and mindfulness. I’ve been practicing ACT since 2008, so for awhile I had to seek out clinical psychologist and psychiatrist who knew the practice (all whom are marvelous folks and who I own so much too). Anyway, it is so wonderful to discuss these principles with so many like minded people! Truly fun!

Have a great ISAD conference!!!

With compassion and kindness,

Scott

Katie, may I inquire if you have ever stuttered? I admire your demonstration of voluntary [pseudo] stuttering. I designed the same exercise for Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy of Stuttering. I show them that it is possible to talk yourself out of overly negative and unhelpful beliefs such as 1) that stuttering is awful, 2) that discomfort that one feels in this situation is unbearable, 3) that frustration due to loss of control–should that happen–can be tolerated, 4) that it in no way diminishes my worth, and 5)that the discomfort of inconveniencing the listener is justified if it helps those who stutter recover from stuttering.

By the way, have you ever stuttered for real? If not, then you really are admirable especially if you model a client’s severe style of stuttering.

Hoping to get to know you better, Gunars K. Neiders, Psy. D.

Hi Gunars,

Thank you for your kind words! I am not a PWS, although according to my mother I had a severe case of developmental disfluency when I was a preschooler (which I have no memory of). So technically I suppose I should say, yes I have stuttered, but I don’t think it “counts”. 🙂

I do try to model whatever “style” of stuttering my clients have when doing these exercises, replicating secondaries, tension, etc. so they can get as close to a “mirror image” experience as possible. If the person has a mild stutter, I’ll aim to make my behaviors more obvious, so that we do get a genuine reaction (positive or negative) from our listener.

It is scary!

Katie,

Wonderful paper. I love the last paragraph – echoes my thoughts exactly on acceptance.

Since this is my first exposure to ACT, I have lots of questions, but I’ll just ask a couple here.

1. I know you’re a fan of mindfulness. How does mindfulness fit into this therapy? Are you working on specific mindfulness strategies during therapy or is it assumed that through this approach the client will become more mindful?

2. This sounds a lot like desensitization that is used frequently in other therapy approaches. I know you touched on this in the paper, but can you explain in more detail the difference?

3. I can see how this would be a very useful therapeutic approach to covert stuttering. Is this an approach you also use with people with a lot of overt, struggled stuttering? What if a client said something like, “I am having these emotions because I am struggling so much to get the word out. If I just didn’t struggle, I would be able to apply these values more effectively.” Would you focus first on the values or the struggle/secondaries (more motor stuff)?

Thanks again. The stuttering community is very lucky to have you.

Courtney

Hi Courtney,

Ah, such excellent questions…

1. That could be a whole paper on itself! I would definitely recommend checking out the other ACT paper at this conference, by Scott Palasik, Dan Hudock, and Chad Yates (https://isad.live/isad-2015/papers-presented-by-2015/research-therapy-and-support/taking-action-and-committing-yourself-to-your-values-acceptance-and-commitment-therapy-for-people-who-stutter/) for one answer. To add to their explanation, I will say that I also like to factor ACT in for “big picture mindfulness”. So often, during a moment of stuttering, there is SO much going on (your internal thoughts, feelings, physical experiences, the listener’s reaction, the environment, the communication dynamic, etc.) and it is very easy to become lost in just one or a few of those things (e.g. the physical tension and “oh no oh no oh no”, while perhaps not attending to your listener or what’s going on around you). So, the goal of mindfulness here is to be able to observe the entire moment, without getting to attached to any one part of it, and then make a values-driven choice about what to do next based on your observations. Traditional ACT therapy does include a lot of explicit mindfulness exercises (breathing, meditation, etc.) but I like to pair that with these more real-world activities. I think sometimes it is tricky to figure out how breathing with your eyes closed in a quiet room translates to giving a speech in front of a crowd, so this is my personal middle ground for making the connection.

2. Yes, this is exactly desensitization/exposure therapy! The purpose of this paper was to take what is a very common and traditional stuttering therapy exercise and “layer” ACT on top of it. Additionally, my hope was that if someone just learned about ACT from a theoretical framework perspective but wasn’t sure how to incorporate it into therapy, that this might illustrate one possible option. Because I was approaching this particular example from an ACT standpoint, I made sure to ask the client certain questions and point out certain occurrences that I might not have if coming from a different approach. Therapy activities are quite useful and flexible in that way…the same activity can be used to help a client experience so many different possible perspectives.

3. Another big questions! Reducing struggle is a very important part of ACT, and there are a number of ACTivities that get at the impact of struggle and how counterproductive it can be (ie, being able to acknowledge and sit with uncomfortable experiences, rather than struggle against them, typically makes values more accessible). To the second part, “it depends on the client” whether we start with more psych vs. physical work (for me, anyway). Even if I start with motor-based work, though, there’s a lot of opportunity to talk about out how the absence/presence of physical struggle applies to ease of speech production. The concept of struggle is always present from the first session, typically…which “struggle domain” we start with varies.

Hello Katie

I notice reading the comments section that one of your hobbies is yoga.

Have you ever considered yoga techniques as a therapy for stuttering? After all it is all about the importance of the breath and releasing tension not to mention visualization. I found it very hard to stutter when talking with plenty of air and a loose relaxed mouth.

Regards

Steve

Hi Steve,

Yes, I do agree that yoga is very applicable to stuttering (and all of life, really…)! I do regularly use yogic breathing cues and exercises when doing mindfulness work, and I also find it helpful for developing awareness of the overall breathing and phonation mechanism. Of course, we know that stuttering is not so easily managed by just saying “breathe more deeply”, but it certainly does have a lot of utility and overlap!

Hello again Katie,

Thankyou for your reply. I have found someone in the stuttering world whos eyes are not going to glaze over when I mention meditation! Please understand I am no yoga fanatic and have never attended a yoga class. I merely took a book on relaxation out of a library 25 years ago and it led me to belly breathing, meditation and visualization. Having recently retired I have had the time to satisfy my curiosity as to why these techniques worked for my stutter. I set out to discover any academic or scientific evidence that would give credence to my journey.

Amongst my discoveries is the effect a few big breaths can have on the balance of the autonomic nervous system and how that can maintain ones positive outlook. Another is how meditation can reduce the size and activity of the amygdala the brains fight or flight centre and the expereiments that have been done with visualization are quite amazing.

I have produced a webpage describing my journey and providing links to the academic work. The page can be found if you Google ‘Breathe like a Baby Visualize like a Champion’ or there is a link on the Stutterfree Steve facebook page.

I have just finished reading a book with many similarities to ACT.

“You are not Your Brain” by Psychiatrist Jeffrey Schwartz on changing compulsive behaviours. He has spent 25 years studying OCD and is an advocate of meditation for training the mind to focus as a focused mind is a mind that can learn. He suggests as part of his therapy using meditation as a way of refocusing on something beneficial when being besieged by compulsive urges which was something I did by using the yogic calming breath frequently! Another technique he has when using similar therapy to voluntary stuttering is something he calls progressive mindfulness. I have a link to one of his lectures on my page and I could literally hear the passion and enthusiasm he has for his subject coming out of the pages of his book.

Please excuse me if I add a line to your last quote but I could not resist! ‘But not on a stuttery short board rather the more graceful long board’.

Regards

Steve

I will have to check out that book! I do agree that breathing in a moment of struggle can be very powerful. I think my yoga has helped me understand stuttering (and the value of mindful breathing)…when I’m in a very uncomfortable pose and DYING to get out of it and move onto something more comfortable, conscious attention to breath can really create a lot of inner change (though the pose continues to be uncomfortable). The same is true for stuttering. Committing to that mindful breathing– in both cases! — is extraordinarily challenging, but the benefits really are amazing!

I love your quote!

Katie,

Thank you for sharing your perspective in this paper. I enjoyed reading this and, as a current graduate student, it was a nice introduction to ACT. I enjoyed reading your discussion about how life is uncomfortable and rather than try to get rid of the discomfort, we should find a way to make it work for people who stutter. I believe this is applicable to all people and it helped me to understand how this reframing of experiences may help those who find common experiences negative due to stuttering.

Thank you Cassidy! I definitely encourage you to read more about ACT; it has so much to offer both in stuttering therapy and in other areas of life. I have found that being an ACT therapist and working with that perspective has really helped me with issues that arise in my own personal life outside of speech therapy. How wonderful that you’ve already started exploring these areas while still a student…you’ll be quite a clinician by the time you graduate!

Hello, Katie,

Thank-you for this very clear presentation of ACT. From my reading of your paper, it shares many of the key concepts of mindfulness that so many people have found useful and that Western science increasingly is documenting not only changes our behavior so that we live with greater ease but the structure of our brain as well.

Choosing to view what we experience inside and outside ourselves as what is and accepting that without lingering resentment or unhappiness is key to living with greater ease and satisfaction, and that includes speaking with greater ease. Acceptance of what is with kindness and compassion to ourselves and each other forms the groundwork for living more as we wish.

Yes, life is difficult. But it needn’t be unpleasant when we learn to accept rather than resist what is.

Best and, again, thank-you for taking the time to share this very useful information.

Ellen-Marie

Thank you for the kind comments Ellen-Marie! I really enjoy your book on the connection between mindfulness and stuttering, particularly how you describe “shenpa”. I frequently quote your descriptions when discussing ACT-related things in therapy. Thank you for all your work!

Hello! What a great read! I really enjoyed your personal story of using ACT! My question is about the values of ACT. I’m sure it really depends on the individual you’re working with, but generally how long should a person focus on one value? Also, could a client get to the value of defusion and have a hard time “unstickying” themselves from the negative thoughts and experiences due to a personal stressor or other factors? How would you address that? Thank you.

Hi Genevieve,

Great questions! As always, the answer to your first question is “it depends”. Values-setting is something that is often done early on in ACT, since it serves as the guiding direction for everything that happens next (is this action/thought process bringing you closer to your values?). There aren’t really a set number of values you need to have or should focus on.

I find in my therapy that many clients express a desire to be more confident. We work to identify what that means and looks like, how are they behaving (what choices are they making, how are they ACTing) when they are living in a confident way. Once that’s clear, we revisit that constantly throughout therapy.

In terms of defusion, this is often a tough one. It can be extremely difficult to separate from negative experiences and stressors, particularly if it was a negative “defining moment” for that person. This can be a long process for people, and requires willingness on the part of the client to let go (again: values– is it worth letting go of this? If we agree on that, then let’s work towards it.) There are lots of great ACT worksheets and experiential learning exercises that can help clients understand the value of defusion, but *actually* defusing can take a while even once we’re on board.

Hello Katie!

I loved reading about that technique for I’ve never heard of ACT before. I am a graduate student for speech and language pathology and I am currently enrolled in my stuttering class. I wanted to share one of my assignments because I think you may appreciate it! We have to go to a public place and stutter to a stranger for 5 minutes and write about our experiences. My professor believes that we need to be able to empathize with our clients entirely to really know how to help them (which I also believe). My question for you: Do you believe this technique could be implemented in a school? Have you ever done this with a young child? Or is this more for the adult population? If so, what modifications would you consider using ACT for a child?

Thank you!

Lisa Ricottone

Hi Lisa,

I think this could absolutely be done in a school setting, although it would really vary on a case-by-case basis whether it would benefit the child. I could see it being useful for some children as young as 6 or 7, there are others as old as middle school for whom it might not be appropriate. It’s very important the child (and clinician!) be able to understand why they are doing an activity like this, what areas of stuttering struggle it targets, and how this activity will move them closer to their goals in therapy. Some people are not “ready” for this activity so it’s certainly something that needs to be introduced at the right time.

This is a great presentation on using ACT with kids who have anxiety (very relevant for stuttering). The themes are pretty much the same, but this has good examples of how we modify language and make some of the experiential learning exercises more active/physical and kid-friendly fun! https://contextualscience.org/system/files/ACT_for_Anxious_Children_Families_Coyne.Davis_.pptx

Hi Katie

I have never read about ACT before, but I think I will be doing a lot more! I really like how this targets the covert aspects, but directly removes the PWS from the situation. I think seeing this occur in the present would prove to be more effective than watching videos, it also allows for instant evaluation.

I was wondering who ACT can used with, i.e. all severities? ages?

Thank you!

It definitely works for all severities and can be applied even with preschool kids (personally I don’t work much with little ones, but I know psychologists who use it with young children for other diagnoses, and can easily see how this could apply and translate for stuttering). I have found ACT to even be very life-changing for my personal life, just as a general approach to daily living, not necessarily for a specific “diagnosis”.

Because the goal of ACT is psychological flexibility, there is a lot of flexibility in how you DO ACT. You may find a particular value is not really a relevant area for a client…so don’t do it. Even though there is an “order” to go through the six values in the handbooks, you can absolutely mix it up if you think that would be better. ACT is very non-regimented.

Excited to hear you are interested! I highly recommend Russ Harris’ book, it is a super-user-friendly introduction, with tons of activities and examples, and a great read.

Hi Katie – thank you for this great paper on ACT. A friend who stutters is very into the tenets of ACT and gave me a link to a publication on the web, which I tried to read and found way to dense and clinical. Your step-by-step breakdown of what it is and how it’s applied in practical situations really makes sense to me. I also agree with your conclusion that even people (like me) who have accepted stuttering are going to have times where they hate stuttering and want it to go away.

Reading some of the other comments, I see ACT is grounded in some mindfulness practices, which I think is key in helping a client more forward in whatever type of therapy they are engaged in.

Your paper sort of reminds me of a paper I wrote for the 2009 ISAD conference, titled “Things I Learned In Therapy.” In it, I talk about being present and in the moment and having the clinician do anything the client is asked to do. Do take a look if your interested: http://www.mnsu.edu/comdis/isad12/papers/mertz122.html

Finally, I’m glad to have read this and to have chatted with you recently in the Google hangout we did. I think it’s crucial for PWS and SLPs to dialogue frequently and learn from each other. -Pam

Hi Pam,

Thanks so much for your response! That was exactly my hope in writing it. I was a bit overwhelmed at my first ACT conference, but doing therapy every day has helped me figure out where the connections are. Theory-to-practice is a doozy. 🙂

I love reading your papers (and your blog, such a wonderful special place for women). Likewise, speaking with you is always a delight. As you know. Looking forward to many more!

Hi Katie,

Thank you for sharing the ACT. As a first-year SLP grad student, it’s nice to learn as many approaches to intervention as possible. I love that ACT is based upon the client’s personal contruct. Would you say that this approach is an extension of Van Riper’s Stuttering Modification?

Thanks!

Amy

Hi Amy,

Yes, ACT can work very nicely with Van Riper’s work. It’s worth understanding though that ACT was not developed with stuttering in mind– it is a psychology approach in the same family as CBT, DBT, etc. Because counseling is such an important part of stuttering, many SLPs who work with stuttering draw heavily from these psychology practices and frameworks. ACT has been used for everything from trauma and addiction counseling to treating depression, OCD, etc. and even in medical counseling for patients with issues such as chronic pain.

The early stuttering philosophers (if we can call them that) really helped pioneer ways to think about stuttering, specifically. For me as an SLP, I find these psychology frameworks helpful in that I can take the principles of stuttering and combine them with a system of thought to work towards goals for the clients.

Hello Katie,

Like the many other comments above, I also enjoyed reading your paper! As a graduate student working with a few children who stutter at a school currently, working toward being “emotionally flexible” and following these principles are great to work toward in therapy. Since stuttering can have such a negative effect on PWS even when they may not have a high percentage of disfluencies in their speech, I can see ACT as being a very effective way to help clients go through many different emotions and work toward being comfortable with being uncomfortable. I read in a previous comment that the entire approach is flexible, but do you find yourself needing to address all of the principles at some point during therapy with a client? Or not all the time?

You also mentioned that during your first voluntary stuttering exercises with a client, they don’t have to talk at all and you do all the talking while stuttering while they watch. Then they try after watching you. I think that is such a great idea! And in your observation, do you see them understanding these values while watching you interact with people or for them to actually do it themselves?

Thank you!

Hi Erin,

This is a great question! I do find that many people benefit more from different parts, so yes, we certainly can spend more time on areas that really need it (as with pretty much anything in therapy!). Sometimes we may only “skim” over a point or two if the person has already sorted that out on their own. I find my therapy often goes in waves of themes…we’ll do Values for a while, then we’ll find ourselves in a place where Defusion is the theme, etc. Because there is no specific order, and all these points build on one another, we often revisit earlier work even if we’ve moved onto a new theme.

As to your second question, it does depend on the person somewhat. I don’t explain ACT to them as explicitly as in this paper (which is written for clinicians), but I do often see that lightbulb, connect-the-dots moment in their head. Some people get a lot out of just watching someone else do voluntary stuttering, others really need to experience it for themselves. (I recently had someone who watched me do two, and we had agreed I would do three before he had to take a turn, but he jumped in and said, “Oh, I want to do one now! This is fun!”) My purpose in doing it before the client is 1) to get buy-in and partnership (“OK, we’re both going to do this scary thing!”) and 2) to help them get perspective on their own experience.

As a graduate student I am currently taking a fluency course and we have learned about many aspects of stuttering. It was great to read such a thorough paper on ACT, I really liked how you took the incentive as new clinician to find something that would benefit your client. I feel that in today’s busy world that some clinicians would have been less willing to find what is right for their client. As a student it is great to see examples of clinicians individualizing their treatment to best fit the needs of their client. The information presented on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) was very insightful. It was very concise and I found it easy to understand. I am looking forward to having the opportunity of using this therapy in the near future. Thanks for sharing!

Thank you for reading, Peter! I’m glad you found it helpful. Best of luck in your continued studies!

Hello Katie,

Thank you for such a wonderful explanation of ACT. Your real-life example made it very clear and applicable. I love the goal of “emotional flexibility.” It seems like this philosophy can be applied to most aspects of life. Do you use ACT often with your clients, and what are their reactions to it?

Thank you for sharing your experience!

Hi Kim,

Ooh, that’s a tricky question. I think in some ways, yes, I am always using ACT…moreso just because it’s influenced my thinking. Even if I’m just having a conversation-based counseling discussion with a person, I listen to their statements and often notice, “Oh, that’s an important value he just expressed right there,” or “Wow, she is really fused to this experience that she had.” I hold on to those nuggets and then reflect them back to the client. “You said that you love meeting new people. But the fear of stuttering seems to be getting in the way of that.” That’s basically counseling 101, but it shows how something as simple as that can be framed in terms of ACT.

A big part of ACT is experiential learning, or basically activities and exercises (such as the one described in the paper) that get the client to “do” something. Usually people really like these activities! They can be a safe, structured way to explore difficult thoughts and feelings and then draw parallels to similar, larger experiences in their day-to-day life. Sometimes it’s challenging, but when done at the right time and with the right guidance, clients are able to see the value and some new perspective which is very rewarding.

Katie,

As many have said this was a great article. I especially love the straightforward manner in which you’ve shared how ACT can be applied in a clinical setting. Although I don’t believe it’s a formal part of ACT, something that has resonated with me is your use of pseudostuttering with this approach to help illustrate values depicted by yourself and the client. I am a graduate student and have had some experience with psuedostuttering during my summer placement (which happened to be with Dr. Dan Hudock and Dr. Chad Yates in their Northwest Center for Fluency Disorders summer intensive program) and like some others I have an assignment which will further my experiences, and I really see the value pseudostuttering has in fluency therapy. Another thing I found insightful was that you indicated throughout the article that you yourself had to apply the principles in ACT to make it through some things (shared in Defusion). I am coming to find that this is definitely a great approach when working with individuals who stutter and it is also something that we as clinicians can benefit from. One point of clarification I have is, when you introduce ACT do you cover all the values of ACT in one session or do you work through it gradually? Thanks again!

Hi Mike,

Thanks for reading and for sharing your experience. I suppose it’s possible to do all six at once, but I typically stick to one or two per session. Six of anything is quite a lot. Even if we’re working on speech tools, I only do two of those in a single session too. 🙂

Also, I don’t necessarily teach this structure and the “six principles” explicitly to clients. I’ll use language that hovers around a certain point, like “Hm, it seems like stuttering is really fused with this identity of X” or “Do you think it would be helpful if we could unsticky these two things?” I DON’T say, “OK Bob, today we are working on defusion, so let’s talk about XYZ.”

Some clients though do enjoy understanding the metaframe and I might teach them a little more about ACT.

A funny story, I had a client who attended a workshop about ACT at an NSA conference, that was aimed at teaching clinicians how to use it in therapy. ACT can seem very metaphysical and confusing when you first learn it, and he expressed to me that he didn’t really understand a lot of what was said during the workshop. Months later, in a therapy session, we were working through a recent experience he had, and I was using an ACT approach. In the middle of the conversation, he exclaimed, “Oh wait! THIS is what that guy at the conference was talking about! Now I understand it!” Not very often I have someone “call me out” on a technique I’m using, but it was a great experience for both of us!

Hi Katie,

Thank you so much for sharing about ACT and your experience actually using it and putting it into practice with a client! Your perspective is so inspiring with the goal of therapy is not to desensitize or remove any feelings a person who stutters has about their stuttering, but instead to embrace those feelings and reactions while allowing the client and showing them how to take a step back and realize that it really will be ok. The life of a person who stutters is about much more than their stuttering moments, and I think it is pivotal for the client and clinician to realize that the moments can be worked through and that everything will be ok.

Thanks again so much!

Thank you for your kind comments, Jess! You summarized why I love ACT wonderfully.