|

Katarzyna Węsierska is an Assistant Professor at the University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland and an SLP at the Logopedic Centre in Katowice. She is a European Fluency Specialist and a coach of the European Clinical Specialization in Fluency Disorders. She was accredited by the Michael Palin Centre for Stammering in London to train Polish SLPs to use the Palin Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for Children. Dr. Węsierska co-organizes the International Conference of Logopedics entitled Fluency Disorders: Theory and Practice at the University of Silesia. She is the main coordinator of the grant project Dialogue without barriers – LOGOLab which aims to improve the quality of therapy for stuttering in Poland. This project is implemented jointly by the University of Silesia, the Agere Aude Foundation and the Arctic University of Norway in Tromsø. At the 11th Oxford Dysfluency Conference she was awarded the David Rowley Award for International Initiatives in Stuttering.

|

It is widely accepted that for therapy to be useful for individuals who stutter, it may address the behavioral aspects of the phenomenon (e.g., stuttering observable characteristics), as well as thoughts, beliefs, and feelings associated with it (Manning & DiLollo, 2018; Yaruss & Quesal, 2004). Current therapeutic approaches promote a community-based model of intervention with the active participation of individuals who stutter and people in the environment such as their families, friends, and partners. Accordingly, as many people as possible should have the knowledge and skills to supportively interact with persons who stutter. Unfortunately, many people in the community, including various helping professionals, have limited knowledge about stuttering and the preferences of people who stutter. This can lead to unintended unsupportive reactions toward people who stutter. One prominent study examined the preferences of adults who stutter (St. Louis et al., 2017), but research is limited on preferences of children who stutter.

The aim of this paper is to present the point of view of children who stutter and their parents on how society can behave in a more supportive way when interacting with them. This will be done by briefly reporting the findings of an international research project conducted among American and European children who stutter and their parents. The direct inspiration for this article was a conversation between this paper’s first author and a teenager after a seminar during which these research results were presented. The young man stated that he agrees that it should also be his task and role to share this information. In his opinion, children whose rights and needs are respected are more prone to become adults who create a society of sensitive, empathetic, and wise people. He admitted that he is passionate and ready to spread current knowledge on stuttering. However, he added: “having easy access to the findings of this study in a place that is reliable and widely respected would be very helpful for me.”

For decades, speech-language pathologists (SLPs) and other specialists who support people who stutter have presented lists of DOs and DON’Ts of what to do or say when interacting with a child or adult. However, St. Louis and colleagues (2017) pointed out that these materials were not based on evidence, even if prepared by individuals who stutter. To fill this gap, research with the use of the Personal Appraisal of Support for Stuttering – PASS/Adult was undertaken in the US and Canada (St. Louis et al., 2017) and then replicated in Europe and the Middle East (St. Louis et al., 2019). The research project featured in this article was an extension of these earlier explorations conducted among adults. This time, an international team of researchers from the USA (M. Weidner, K. St. Louis, K. Scaler-Scott, C. Coleman), Norway (H. Sønsterud, S. Skogdal, K. Åmodt), Poland (K. Węsierska), and Slovakia (H. Laciková) were involved in this study. Children who stutter and their parents from Poland, Slovakia, Norway and the USA were asked to complete the child and parent versions of the PASS questionnaire (St. Louis & Weidner, 2015ab). This mixed-methods study sought to investigate the perceptions of supportive or non-supportive actions or responses from others and to compare results across groups. Children and their parents completed the child or parent version of the PASS-Ch or PASS-P in their native language. Both versions include 37 items which measure respondents’ perceptions related to degree of helpfulness of others’ responses (e.g., finish my words, feel sorry for me) and the amount of help the child has received from various people or groups (e.g., teachers, classmates). Responses are rated on a 1-5 Likert scale, with higher values reflecting higher levels of perceived support. In addition, both versions include open-ended questions to provide qualitative data relative to children’s and parents’ lived experiences. A total of 422 participants (151 children and 271 parents) completed the survey from Poland, Slovakia, and the USA, and 11 Norwegian participants completed the semi-structured interview. The average age of child respondents was 10.9 years, and most children had at least one year of stuttering therapy.

Based on the survey data, the top three most helpful and unhelpful listener supports, as reported by children and parent groups, were extracted. For a group of children, the three most supportive behaviors were: “be patient,” “maintain normal eye contact,” and “include me.” While in the group of parents it was: “be patient,” “know how to react,” and “maintain eye contact.” With regards to the least helpful listeners’ supports, children pointed out: “laugh at me,” “use the term stutterer,” and “ignore me.” The parent group indicated the following responses: “laugh at my child,” “finish my child’s words,” and “pity my child.” In addition to the very helpful and unhelpful supports, the items in the neutral range should be also taken into account. For the children’s group these were: “think about what I want to say” and “slow down,” while the parents’ group neutral ratings included: “telling my child to use strategies” and “ask how to help my child with his/her stuttering.” It appears that it should be more commonly understood that specific advice given at the moment of stuttering is highly variable and individualized. Another interesting finding from this study is that parents and children in all of the countries rated SLPs and parents as the most supportive groups. Moreover, the children’s group identified people talking about their stuttering on television, YouTube, social media, the Internet, etc. and their classmates as the least helpful sources of support. The parents’ group identified classmates as being the least supportive group. Preliminary qualitative results from six Norwegian children (6 boys) and five parents (2 fathers; 3 mothers) supported the quantitative results. Overarching themes pertaining to helpful listener supports include: patience, acting normally, and fostering a positive environment to talk openly about stuttering. Little variability existed in the rank-ordering of most and least helpful listener supports. However, other variables such as giving advice on what to do and how to feel, asking questions about stuttering, and meeting other people who stutter were highly diverse. Based on this study, there is strong evidence of several universal “dos and don’ts” when talking to children who stutter, but preferences have to be individualized. Future replication studies in various countries will be important to confirm these findings. Based on results from this study, we advance this summary statement, which is adapted from similar work with adults by St. Louis et al. (2017, p. 10):

When interacting with a child who stutters, be patient and friendly, while maintaining natural eye contact and body language. Focus on the content of the child’s message, not whether it was fluent. Avoid finishing the child’s sentences or providing unsolicited recommendations. Be mindful that seemingly well-intended comments (e.g., telling the child to “slow down” or “think about what you want to say”) or actions (e.g. making a joke about stuttering) can often be undesired or unhelpful. Children who stutter will have individual preferences for responses they feel are helpful. It is important to establish a trusting relationship and talk openly with each individual to identify those preferences, so they can receive maximal support from those with whom they communicate.

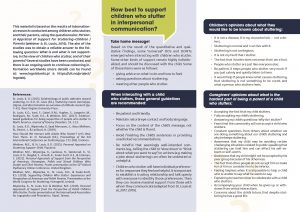

Taking into account the study findings, it seems that three issues should be highlighted. On the one hand, considering how important parents are as a source of support, they should be empowered. Also, they should be aware that they are the children’s most important advocates. It is important that they believe in their strength and have the power to educate others. In turn, understanding the highly individualized nature of children’s preferences informs us – professionals (SLPs and teachers) – that we should listen to them and ask them how they want us to be supportive listeners. With this in mind, the Norwegian-Polish team created guidelines and preventive materials to disseminate this study findings. It was possible thanks to the grant project ‘Dialog without barriers – LOGOLab.’ This project has been implemented jointly by the University of Silesia in Poland, the Agere Aude Foundation and the Arctic University of Norway in Tromsø. As part of this project, various intellectual results were created, one of them was evidence-based guidelines on how to interact in the most supportive way with children who stutter. These guidelines are available in English and Polish on the LOGOLab grant website. The Norwegian-Polish team (K. Åmodt, T. Anderson, A. Boroń, I. Michta, M. Pakura, A. Sakwerda, S. Skogdal, H. Sønsterud, and K. Węsierska, supported by M. Weidner and K. O. St. Louis) developed a preventive poster and a leaflet to make the contents more accessible and user-friendly.

Illustration 1: The LOGOLab poster

Illustration 2: The LOGOLab leaflet (part one) Illustration 3: The LOGOLab leaflet (part two)

All these materials in both versions (English and Polish) are available in open access on the LOGOLab website. The authors would be delighted to make these available in other languages. We welcome anyone wishing to translate the poster or leaflet to another language to contact Katarzyna Węsierska.

The authors are convinced that it is time for change. It is time for the general public worldwide to know that stuttering is ‘whatever people who stutter feel their own stuttering to be’ (Shapiro, 2011), and that people who stutter have the same rights as the rest of society. It is time for communities to change and to break down barriers to communication when interacting with individuals who stutter. This must be done by listening and learning in a greater sense from them. It is also time for SLPs and teachers to implement their ideas and individual wishes in the therapeutic processes or in the educational settings. Last but not least, it is time for children who stutter and their parents to be given more space for the choices they make, that they should trust their intuition so that they can confidently speak the changes they wish to see!

References:

Manning, W., & DiLollo, A. (2018). Clinical decision making in fluency disorders. (4th edition). Plural Publishing.

Shapiro, D. A. (2011). Stuttering intervention: A collaborative journey to fluency freedom (2nd edition). PRO-ED.

St. Louis, K. O., Irani, F., Gabel, R. M., Hughes, S., Langevin, M., Rodriguez, M., Scott, K. S., & Weidner, M. E. (2017). Evidence-based guidelines for being supportive of people who stutter in North America. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 53, 1-13. doi.org/10.1016/j.jfludis.2017.05.002

St. Louis, K.O., Węsierska, K, Saad Merouwe, S., Abou Melhem, N., Dezort, J., & Laciková, H., (2019). How should we interact with adults who stutter? Let’s hear from them. In: D. Tomaiuoli (Ed.), Proceedings of the 3nd International Conference on Stuttering, pp. 172-183. Erickson.

St. Louis, K. O. & Weidner, M. E. (2015a). Personal Appraisal on Stuttering Support–Child. Populore.

St. Louis, K. O. & Weidner, M. E. (2015b). Personal Appraisal on Stuttering Support–Parent. Populore.

Yaruss, J. S., & Quesal, R. W. (2004). Partnerships between clinicians, researchers, and people who stutter in the evaluation of stuttering treatment outcomes. Stammering Research: An on-Line Journal (published by the British Stammering Association), 1, 1–15.

![]()

Hello, as an aspiring SLP, this paper has given me such insight on how a community should behave. I find it ironic how we are so quick to correct a child’s behavior when we are the ones who need correcting. The change is in our hands to make this world a better and happier place for a child who stutters. Since the U.S is considered A individualistic society, compared to other countries which are more of a collective society, is it possible that other countries are more accepting and empathetic to PSW?

Hi Gina,

Thank you for such a wonderful response. I especially like your comment that “we are often the ones that need correcting.” What we know about public attitudes to date does not suggest that one country is far superior than others. In fact, adults and children have fairly similar stuttering attitudes cross-culturally. Ken St. Louis has looked extensively at a lot of variables: culture, sex of respondent, SES, etc. There are some nuances, but they are hard to pinpoint as “causal.”

In addition, many countries still have very strong stigmas toward any type of disability – even though the US is FAR from accepting of all disabilities, some very big important movements through the 1970’s and on have really allowed the general public to talk openly about disability and establish some legal protections for persons with disabilities (even though such protections are woefully imperfect). I hope we can see a global movement that accepts and integrates persons of all abilities.

The long answer to your great question is: we don’t really know, but the research does not lead us to believe that being an individualistic society leads to less accepting attitudes towards PWS.

I am very happy to read this paper and hope it is read and acted on by others! I agree that working with children who stammer needs to change. Many traditional therapies rely on parents following a series of rules based on numerous variables which are impossible to follow and achieve sustainably. I would also argue that the rules suggested are often detrimental to the future well-being and ease of being of the child and the parents, especially those children and the parents of those children who continue to stammer. For the past few years in Bradford U.K. our stammering service has used a simplified accepting approach very similar to what you suggest. We base early years parent support on education about stammering, acceptance of stammering as a difference, giving time (patience) and most importantly empowering parents and in the long term children to advocate for themselves. I think openness is really important for this. Children need to witness parents advocating for them so that they learn the language and have the self belief to do it for themselves. Empowering parents to empathise with their child’s distress and struggle is also important so that children learn emotional language that they can express themselves in the future – the language of assertion. I am really interested in the ‘include me’ aspect and will reflect on this more.

Thanks so much for your lovely comments!! Regarding your comment about emotional language: YES!! Absolutely – often, young children do not have the emotional lexicon for nuanced feelings. Rather, they often box them into broad categories: mad, sad, happy. One thing that we try to do is broaden that lexicon to include emotions such as “frustrated, confused, disappointed” – it is wonderful for parents to assist with this, as they know their child best: they can interpret/label/define that emotion, which is so important in the therapy process!

Hello Hilda,Mary and Katarzyna, as an aspiring SLP, this paper has given me such insight on how a community should behave. I find it ironic how we are so quick to correct a child’s behavior when we are the ones who need correcting. The change is in our hands to make this world a better and happier place for a child who stutters. Since the U.S is considered A individualistic society, compared to other countries which are more of a collective society, is it possible that other countries are more accepting and empathetic to PSW?

Hello Gina!

Thank you again for your comments – as well as your question about cultural differences. For sure there are cultural differences when public attitudes towards stuttering are concerned. As already pointed, the work of Kenneth St. Louis and colleagues have collected data (Public Opinion Survey of Human Attributes-Stuttering or -Cluttering) from several countries worldwide, and which also contain data from a huge amount of countries – including from all continents. The results are showing great differences between country-to-country. Regarding your terms ‘individualistic society’ vs. ‘collective society’, it is difficult for us to explain cultural differences within these terms. As Mary is mentioning above, there are several variables which are influencing the public attitude between countries. Most likely the form of government in each country might be included as an important variable too, regardless if the country would be defined as ‘individualistic society’ or ‘collective society’.

Bravo, Hilda,Mary and Katarzyna!

There are so many excellent points that you make. many were known intuitively but having research bear them out is incredibly important.

Thank you all so much for the work that you do. You change – and save – lives.

Hanan

Thank you so much, Hanan!

Your words are highly appreciated!

We want to thank you as well, Hanan, for all the great collaborative work you are doing at an international level!

We as well, advocate an active role for the person who stutter as chief stakeholder in practice, and a complementary n = 1 approach. For sure, there is still lots of information which is needed to fill the gap between research and best clinical practice. We believe that this gap is best bridged by focusing on the persons themselves in a way that simultaneously advances the field of speech-language therapy. This collaborative project is only one idea to fill this gap, and we are looking forward to continue this work.

We are wishing you and the dedicated ISAD team a happy and meaningful Stuttering Awareness Day!

Hi Mary, Hilda and Katarzyna, any research that can clearly show us how to be allies is of great importance. Thank you for this!

I am ready to translate into Spanish the material you need, please do not hesitate to write me at fono.tamagnone@gmail.com

Kind Regards!

Dear Fernanda, Thank you for your kind words. It is lovely that you are ready to translate the poster into Spanish(and possibly the leaflet as well).Please don’t hesitate to do so. As soon as you have the Spanish translation ready, please contact me again (katarzyna.wesierska@us.edu.pl). I will get the graphic designer who will prepare the Spanish versions of these materials. We will be delighted if these preventive materials are available in other languages. Thank you for your readiness to support the dissemination of our study findings and empower children who stutter and their parents so they can speak about the changes they wish to see. sincerely yours, Katarzyna Węsierska

Hi

I really support your paper (I have already commented on it above) but after reviewing the posters I must say that I am disappointed in the first sentence of the section, ‘More about stuttering…’:

‘Stuttering is a complex fluency disorder.’

In light of the later section ‘Children’s opinions about what they would like to be known about stuttering’ e.g.

• It is not a disease, it is my characteristic – not a defect…

and also more generally in reducing stigma about stammering, do you think it is helpful to define stuttering using jargonistic, medical language?

How about, ‘Stuttering is a variation of speaking…?’

and, ‘change the rhythm of speech’ rather than ‘disrupt the rhythmic flow of speech.’

If we want to ‘see’ change in therapy and want people/parents to accept stammering we need to change the way we think, write and speak about stammering; step back and view the language and definitions that are used on automatic with a wider angled lens…speak and write the changes that we wish to see…

With best wishes,

Kathryn

Hi Mary, Hilda, and Katarzyna — Thank you for sharing your research, thoughts, and conclusions on best practices to help be the most supportive and beneficial clinicians for individuals who stutter.

I’m a Post Baccalaureate student studying to be a SLP and I appreciate your emphasis on the importance of a community-based model of intervention. It’s so crucial to include the people who make up a child’s inner circle in their speech therapy journey in order to help educate and guide them on how to be the most effective support system.

I was curious if you’ve worked directly with classroom teachers to help educate them on how to supportively interact with students who stutter and what that looks like? I currently work at an elementary school and often times see a disconnect when it comes to including the teachers with the best tools to advocate for a student who stutters.

Thanks in advance for you time and thoughts!

Bree

Hi Bree –

Thank you very much for your comment. Indeed, collaboration with classroom teachers is critical. When I worked full-time clinically, I was in an hospital outpatient setting, but I still made a point to connect with the school teachers as needed (email, phone, notes, etc). I wanted to ensure my goals were functional and to get a sense of how that child is participating (or not) in the classroom/with peers. I also used those conversations as a springboard to provide educational materials about stuttering and how to support children who stutter in the classrooms. Most teacher prep programs don’t teach about stuttering, so it is up to the SLP to fill that gap. The National Stuttering Association has some great ready-to-go materials you might find useful:

https://westutter.org/teachers-educators/?cmpn=Non-Brand%7CUSA%7CDSA&device=c&kw=&adpos=&gclid=CjwKCAjw8KmLBhB8EiwAQbqNoEXjn52M8EBNewdBqtkeDz1OMJY61U7AqJrOJVR2sYxkNkiq-8W9shoCZFUQAvD_BwE

Hi Mary,

I appreciate you taking the time to share your insight and provide this link to additional resources/materials. I completely agree that this collaboration with classroom teachers is crucial and hope to continue sharing these materials with our teachers to create the best environment possible for our students who stutter.

Appreciate your feedback and thank you again,

Bree

Dear Katarzyna, Mary and Hilda,

Thank you for this wonderful paper addressing the importance of listening to children who stutter and understanding their preferences for supportive listening. I have been grappling with this issue recently as a student who is aspiring to be an SLP, so I greatly appreciate your evidence-based information on best practices for interacting with children who stutter.

I found it disheartening that children found people talking about stuttering in the media, such as on tv, youtube, and social media the least helpful in terms of support. If we want the world to change their understanding of stuttering and how they approach people who stutter, I feel that there needs to be better representation and dissemination of these concepts in the media, so that this knowledge can reach the masses as opposed to just SLPs and people who stuter. What changes would you like to see in the media that might improve this situation? Thank you!

Laura

Thank you for sharing your research about best practices when interacting with children who stutter and their families. I am a second year graduate student studying Speech-Language Pathology. Although I have limited clinical experience working with people who stutter, I am thankful for resources like these that empower me to provide evidence based care to my future clients.

I think this article does a great job of busting the myth that there is a one size fits all list of how to interact with an individual who stutters. I appreciate the emphasis you have put on the importance of personalizing each interaction to the person, as their preferences may be different than another individual who stutters.

I was wondering what insight you had on collaboration with classroom teachers and school based initiatives to increase awareness about stuttering. I am based in the United States, but I am curious about international programs that aim to educate and bring awareness to the public about stuttering. Do these programs exist? Are they research evidence based? What are the barriers a program like this may face in the school setting and beyond?

Thank you again for your insight and information on how I can personally be a more supportive listener!

How I love your paper. <3 After being a leader for children and youth camps for many years, this so resonates with me. As we get the stories that both parents and children not really want to share. Parents often come with misconceptions and guilt, feeling lonely with their thoughts, thinking that the only way to happiness is through fluency, why it can be as simple as "I hear and accept you". Children tell stories of being pushed into therapy, while the only thing they want is to say what they want to say, without judgement. And so often parents and children don't even tell each other what they really feel, and ask the other how they can help each other. Stuttering would be much less of a problem, if we talk about it and listen to each other. As there is no one solution, being the strong individuals we are. I'd so much like to see more disciplinary approach, where parents, children, SLPs, family members and friends all are invited into the therapy room, with SLPs, psychotherapists, physical therapists, a masseuse, a choir leader, a clown, PWS, etc all surround that one person who stutters, and together help the client to find that solution that fits this very client. Research is needed to convince the world where the problems are and what the solutions can be, but in the end, each individual needs an individual approach. And that might be much more simple to reach if we communicate our problems and solutions. :.-)

Keep them talking

Anita

Dear Anita!

Thank you so much for your wonderful feedback! It is highly appreciated!

You are a person who is informing and describing stuttering, stuttering therapy and the need of considering interdisciplinary collaboration in a very wise and holistic way. Keep up with the important work you are doing, both at a national and an international level.

Wishing you all the best!

Hello,

Thank you all so much for this research presentation! It’s so important for everyone to learn and be aware of the actions that we take towards people who stutter and how it affects them. We need to be thoughtful in our interactions and be sure to use words that are encouraging. Looking forward to see how this research will start a more potent conversation in the PWS and SLP communities, among others!

– Jillian