About the Authors: My name is Daisy Hope and I am a Specialist Speech and Language Therapist at the Michael Palin Centre for Stuttering in London, UK. I first became interested in working with people who stutter whilst on a placement at City Lit (also in London) and have developed as a specialist over the last 3 years.Since starting at the Michael Palin Centre, I have particularly enjoyed working with families and hope to develop my therapeutic skills further by training in systemic/ family therapy in the near future. About the Authors: My name is Daisy Hope and I am a Specialist Speech and Language Therapist at the Michael Palin Centre for Stuttering in London, UK. I first became interested in working with people who stutter whilst on a placement at City Lit (also in London) and have developed as a specialist over the last 3 years.Since starting at the Michael Palin Centre, I have particularly enjoyed working with families and hope to develop my therapeutic skills further by training in systemic/ family therapy in the near future.

I work with clients who stutter from pre-school through to young adults and provide family-based, individual therapy and group therapy. I also enjoy supporting the skill development of other speech and language therapists through teaching and providing advice or supervision. |

Parental involvement in therapy is essential within most evidenced based approaches for preschool children who stutter (e.g. the Lidcombe Program, Palin Parent Child Interaction, Family Focussed Treatment or RESTART-DCM). Increasingly, researchers and clinicians are considering the possibility that this may be one of the common features of such approaches which may be central to their effectiveness (e.g. De Sonneville-Koedoot et al 2015).

In the UK, once children reach school age many services move away from clinic-based therapy towards therapy being provided within schools. This, alongside increased use of direct therapy and the absence of an established, evidence based family-based alternative may contribute to less frequent involvement of parents in therapy for older children. At the Michael Palin Centre, we have found that involving parents, and often other family members in therapy, is essential for many school-aged children up to and including teenagers. All can benefit from therapy providing a safe space in which they can ‘speak their minds’ and be heard by those most important to them.

Why do parents of school-aged children need the chance to speak their minds?

Parents of children who stutter frequently report feelings of stress, uncertainty about the nature of stuttering and anxiety regarding how to respond to or talk about stuttering with their child (Millard & Davis, 2016; Plexico and Burrus, 2012). Many parents also carry a sense of guilt; that somehow something they did or didn’t do along the way has led to their child’s stuttering. So parents can benefit from therapy for themselves to help them work through their worries and complex emotions, allowing them to re-establish confidence in their parenting skills and be the best support they can for their children.

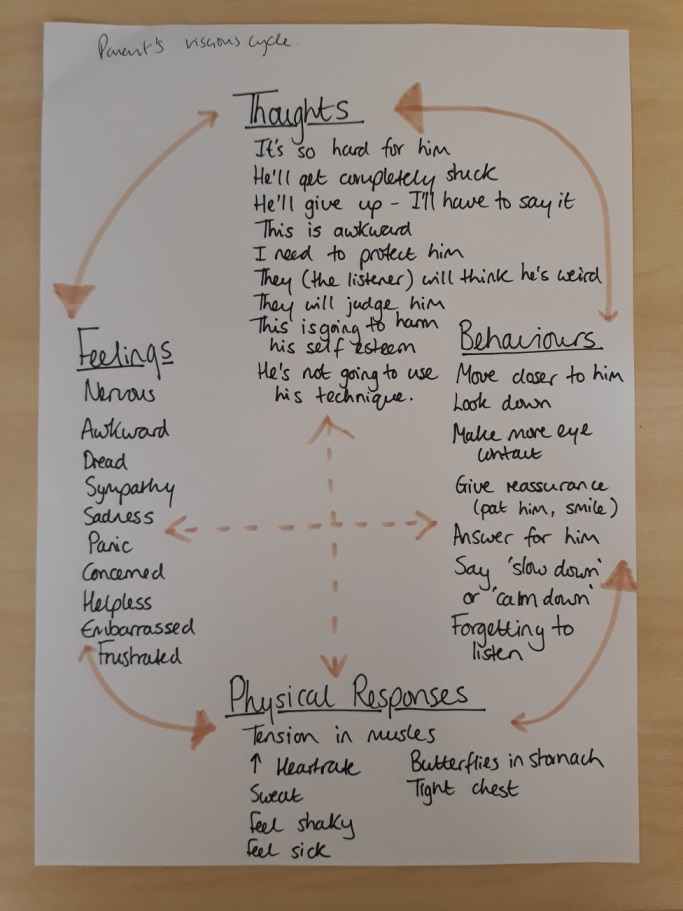

From a cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) perspective, ‘negative automatic thoughts’ are positioned as the main driving force behind the often strong emotional responses to stuttering. In turn, these lead to physical responses by the body which influence the way we respond and behave; primarily by triggering the ‘flight-fight-freeze’ response. Together this is referred to as the ‘cognitive cycle’, or a ‘vicious cycle’. This framework can be a way of better understanding normal human emotional responses and behaviour. This model is commonly used with children and adults who stutter (Kelman & Wheeler, 2015; Menzies et al., 2009), but it can also be used to help us understand parents’ experiences and the impact of this on communication and the therapeutic process. Here we will explore aspects of the vicious cycle as it relates to parents of children who stutter.

Some parents have described their minds becoming “flooded” by worries as soon as their child stutters, for example: “if he’s like this with me, how will he ever talk to children in his new class”, “he’s not going to be able to say it”, “he’ll get laughed at”, “I’m not patient enough…I’m a bad mother”.

Parents have described many different emotions, for example feeling anxious, on ‘high alert’ and panicked in response to, or in anticipation of, their child stuttering. Some describe feelings of embarrassment or impatience. For many parents, experiencing such emotions can trigger secondary emotional responses, for example feeling guilty that they are impatient.

Figure 1: A parent’s vicious cycle in response to their child speaking to their teacher

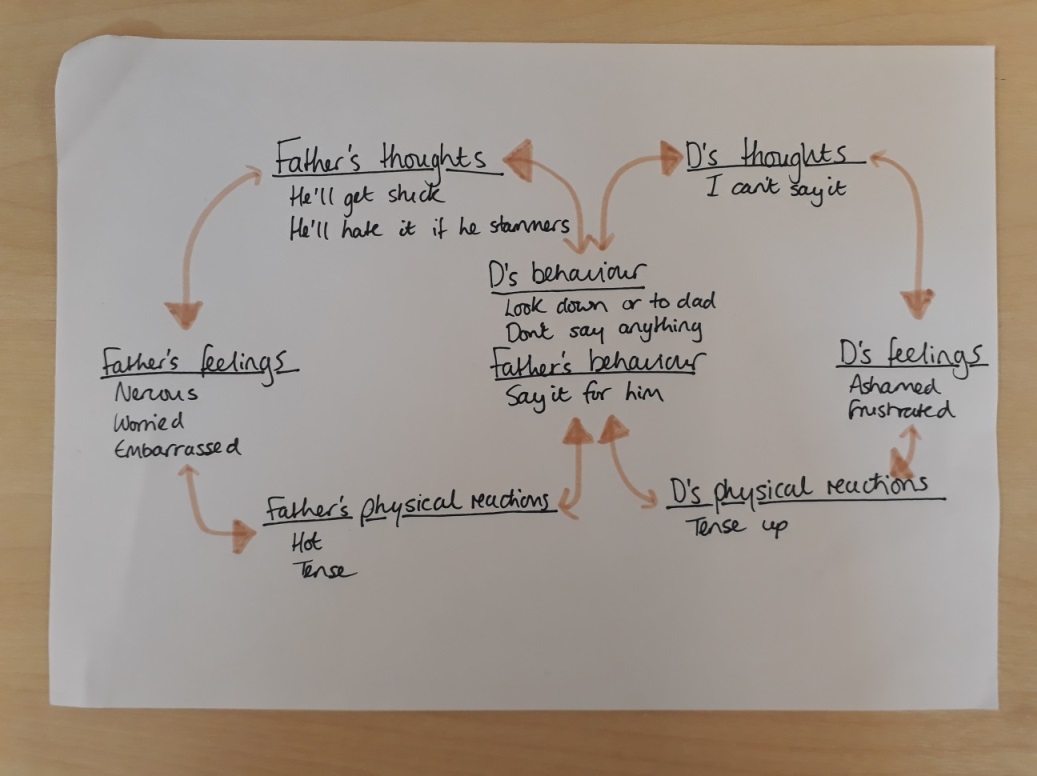

Within families, how one person thinks, feels and behaves has a knock-on affect on how others think, feel and behave (see Biggart, Cook & Fry, 2007). This is possibly particularly relevant for stuttering as it exists primarily within interactions between people. This interplay between the responses of parents and children can be referred to as the ‘systemic bowtie’ (Neimeyer, 1993). Figure 2 details the responses of a father and his 10 year old son who stutters.

Figure 2: A ‘systemic bowtie’ for D and his father

In the example, the outcome (the child taking a step back, and the father speaking on his behalf) is at least in part driven by the father’s anticipation of the stuttering, the prediction that his son will “hate” the experience, and the associated emotional and physiological response those thoughts elicit. As a result, D will not get the opportunity to prove either to himself, or to his father that he can say it. By the time children reach school age, they are increasingly aware of the responses of others to their stuttering and most can give examples of what the people around them do when they stutter, for example ‘my mum tells me to take a breath’. By providing a therapeutic space in which parents can acknowledge their own feelings and voice their worries, parents can become more aware of them, and of the possible impact of their emotions on their own responses and any subsequent impact on the child. They then can actively choose to do something different, possibly something which may be considered more helpful by their child.

Of particular relevance, when working with school age children is the transition from working with children for whom ‘recovery’ is considered possible to therapy as being a way of supporting children to manage their ongoing stuttering as effectively as possible. The extent to which parents have considered the potentially chronic nature of their child’s stuttering will vary and the journey of coming to terms with this possibility will be different for everyone. When considering the longer-term view parents inevitably express worries about the child’s future; their ability to get a job, go to university, make new friends. Others may look back; ‘what if we had come to speech therapy sooner?’, ‘what if we had done more practice of the strategies?’, ‘what if I’d had more time to spend with the children?’….. By allowing parents the space to voice their worries we can be in a position to support them through this transition, provide accurate information and reassurance.

Parents who stutter themselves may particularly benefit from being given the chance to speak their minds. Some will have had their own negative experiences; bullying they experienced, or jobs they have been turned down for, which may affect how they anticipate their child’s future and add to their concern for their child. Others may be fully accepting of their stutter and find it harder to understand why their child struggles with it. Some will have had their own experience of speech therapy which will help shape their expectations and opinions about what we as therapists should and can offer.

How will giving parents the opportunity to speak their minds influence therapy outcomes?

Involving parents from the start of the assessment process allows us to fully understand children’s stuttering over time, across different settings, to understand the often complex interplay of factors which may influence fluency and communication both in the past and in the present (see Kelman & Nicholas, 2008 for more detail). Parents are able to provide detail and insight about temperament, linguistic, physiological and environmental factors that are relevant and that contribute to the development of an individualised therapy programme. For example, if parents inform us that their child is generally highly emotional, or that they feel unsure about how best to support them with managing their emotions, or that the child stutters more when their emotions are running high, then our recommendations for therapy are likely to include support for the family in dealing with feelings.

Most parents will bring their child to therapy with some expectations about what will be done, how it will be done, and the ultimate outcome. The therapy we offer may well be consistent with parents’ expectations, however in some cases it may not. Giving opportunities to express their ‘best hopes’ about what they or their child may gain from therapy allows for genuine joint goal setting whilst trying to align parents’ and children’s goals, and opens up discussion about what may be ‘realistic’ or achievable therapy outcomes (Berquez et al., 2015).

Continuing to bring parents’ voices to the fore throughout therapy is invaluable as parents’ and their children’s emotional and behavioural responses to stuttering become inextricably linked – as illustrated in the ‘systemic bowtie’ (Biggart et al. 2007). Just as for children who stutter, talking about stuttering can be important in the process of ‘desensitisation’ for parents (for more detail see Berquez & Kelman, in press). Therapy can provide parents with an opportunity to explore ways of talking about stuttering that makes sense for them and their child. By learning about stuttering alongside their child, developing a shared understanding and a vocabulary with which they can talk about it together, an environment in which it is OK to ‘speak your mind’ can be created.

Therapy sessions can become a starting point for further discussion at home and within the wider family by creating a space where both children and their parents can openly speak about stuttering. This can be enormously helpful in the process of taking what has been covered in sessions into everyday family life and may be one factor that helps to maintain therapeutic change (Fower, unpublished 2016).

Parents’ perspectives will be an important consideration when evaluating the outcomes of therapy. They can provide information about the severity and impact of stuttering across different situations as well as an insight into transference of skills outside of the clinic context (Millard & Davis, 2016). Involving parents in decisions regarding the direction of therapy and being involved in the process from the beginning, can help parents to feel more satisfied with the therapy, more knowledgeable and more confident in their own ability to help their child to make progress (Plexico & Burrus, 2012), and thus increasing chances of successful outcomes, whatever that might mean for them.

Parents of school age children have just as much to contribute and gain from involvement in the assessment and therapy process as those of pre-schoolers. They are dealing with the additional stresses associated with coming to terms with the increasingly chronic nature of stuttering and need to be equipped to deal not only with their own emotional and behavioural responses, but those of their child. Therapy is likely to be more appropriately focused and ultimately more successful if parents are given the opportunity to ‘speak their mind’ and to have those opinions listened to and taken into account during all steps of the therapy process.

References

Berquez, A., & Kelman, E. (In Press) Methods in Stuttering Therapy for Desensitising Parents of Children who Stutter. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology

Berquez, A., Hertsberg, N., Hollister, J., Zebrowski, P., & Millard, S. (2015). What do children who stutter and their parents expect from therapy and are their hopes aligned?. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 193, 25-36.

Biggart, A., Cook, F. & Fry, J. (2007) The role of parents in stuttering treatment from a Cognitive Behavioural Therapy perspective. Proceedings of the Fifth World Congress on Fluency Disorders, Dublin, Ireland, 25–28th July, 2006.

de Sonneville-Koedoot, C., Stolk, E., Rietveld, T., & Franken, M. C. (2015). Direct versus indirect treatment for preschool children who stutter: The RESTART randomized trial. PloS one, 10(7), e0133758.

Fower, K. (2016) Post-therapy experiences: what can we learn from parents of children who stutter? Unpublished manuscript. University College London

Kelman, E., & Nicholas, A. (2008). Practical intervention for early childhood stuttering: Palin PCI approach. London: Speechmark.

Kelman, E., & Wheeler, S. (2015). Cognitive Behaviour Therapy with children who stutter. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 193, 165-174.

Menzies, R. G., Onslow, M., Packman, A., & O’Brian, S. (2009). Cognitive behavior therapy for adults who stutter: A tutorial for speech-language pathologists. Journal of fluency disorders, 34(3), 187-200.

Millard, S. K., & Davis, S. (2016). The Palin Parent Rating Scales: Parents’ perspectives of childhood stuttering and its impact. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 59(5), 950-963.

Neimeyer, R. (1993). Constructivist approaches to the measurement of meaning. In G. Neimeyer (Ed.), Constructivist assessment: A casebook (pp. 58-103). London: Sage

Plexico, L. W., & Burrus, E. (2012). Coping with a child who stutters: A phenomenological analysis. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 37(4), 275-288.

![]()

Many thanks for this interesting and enjoyable read, and the useful signposting to relevant literature.

Dear Kirsten,

Firstly I apologise for the delay in responding, I have been having trouble signing in. Thank you for your kind feedback, I’m glad you enjoyed reading the article.

Best wishes,

Daisy

HI, Daisy. I enjoyed reading your paper. Thank you for reminding us to include parents of school-age children in the assessment and treatment processes. I’ll follow this advice with some of my clients’ parents who have shown interest in being part of the therapy sessions. Do you have any relevant handouts for parents?

Dear Lourdes,

Firstly I apologise for the delay in responding, I have been having trouble signing in. Thank you for your kind feedback, I’m glad you enjoyed reading the article and are considering involving parents in your therapy sessions. I hope you will experience how effective it can be to include them in discussions. We have lots of information on our website for parents: http://www.michaelpalincentreforstammering.org/ . It depends on the age of the client, however we also have lots of hand outs for parents of younger children (roughly under 7) within the Palin Parent Child Interaction Therapy Manual. I may be able to give more specific suggestions if you give some ideas of topic that would be helpful to you and your parents.

Thanks again and best wishes,

Daisy

Thank you for this interesting paper. As one of the leaders of over 30 children camps in Sweden, I recognize a log of concerns parents have. That’s why we have two children camps. The first one is for one CWS and one parent. After playing with the whole group to gain their trust, the next day we seperate the parents from the children. The parents are together in one group with two SLPs and talk, watch videos and other material, discuss thoughts and fears, and get all the knowledge and advice they can carry. In the meantime the leaders take the kids and… play! Games, zoo, swimming, science center, you name it. No therapy,just play (and do games that will make them talk). In the evening we meet again, play with the whole group (also the SLPs, to show the kids they are as much fun as everyone else). And the next day we are in seperate groups again. This way we create a place where both parents and CWS feel free to speak up and speak their minds.

The second camp is a follow up. Here the children can bring their family members. The only “working” session is where parents have some hours to speak without the children around and talk about progress, worries, etc, and speak to a mother to a CWS and/or an adult who stutters. To bring the whole family together is important for all involved, but especially to siblings, who now are no longer in the center, and grandparents who watch their grandchild bloom and speak up.

I so wish SLPs would bring others in the therapy room as well. Other family members who have a hard time accepting the CWS. Friends, who learn about stuttering and can help to do assignments, and are easier to share emotions with once they understand more. It takes a village to raise a child. 🙂

Happy ISAD and Keep talking!

Dear Anita,

This sounds like a really great opportunity for your children and their families. We also run groups for children in which parents are required to attend – they are as involved as the children in the therapy process. Similarly to your group, the parents have a chance to talk about their experience of parenting a child who stammers and work with other parents to develop their confidence in dealing with challenges that can arise from having a child who stammers.

Your group sounds like such fun, and a really helpful experience for the whole family.

Thank you for your feedback. Best wishes,

Daisy

Hi Daisy

I really enjoyed this well researched paper and all the important outcomes that result when parents are involved and actually learn about, and from maybe, their child’ stuttering.

You mentioned parent guilt. My father would not allow me to attend speech therapy in school, even after being specifically referred in third grade. He was adamant that it wasn’t going to happen, to the point where he pulled me and all of my siblings out of the public school we were attending and sent us to a catholic grade school. There was no speech therapy offered there and of course no one was going to pay for private therapy.

So I had none and was alone with my thoughts, worries, fear and shame that was quickly developing as third grade me began to believe I was the only one afflicted with “this” and it was so bad no one even wanted to talk about it.

Years later, as an adult, after a brief, unsuccessful foray into fluency shaping therapy, I finally found the support community. I started talking about stuttering.

My mom cautiously broached the previous untalked about issue of stuttering and found the courage to tell me how incredibly guilty she’d always felt, for years. She told me she deeply regretted not standing up to my father and insisting I get help. She actually felt massive guilt for not standing up to him and standing her ground for many other things regarding her 6 kids.

So here I was, for so many years hiding stuttering and being consumed by deep shame and I later learn that my mother had been carrying around deep guilt for close to 40 years. Things could have been so different.

Today’s kids who stutter and their parents who join them on the journey are likely becoming so much better prepared to roll with the flow of stuttering and truly make it just one of many parts of the child. And not the main defining part of the kid, which I believed about me. I worked furiously to cover up the big “S” cape I felt everyone always saw.

Thank you for all the work you do and for this wonderful ISAD contribution.

-Pam

Dear Pam,

Thank you for your considered and personal response. It sounds like you, and your family had a really difficult journey. I am so pleased that you have since found a way to deal with your stuttering that feels right for you, and you and your mom have found a way to broach the subject. What a relief that must be. The ‘conspiracy of silence’ that you speak of can be all too common within families, and of course by involving parents in the therapy process, and allowing stuttering to become something that can be spoken about openly within families, perhaps it can be avoided.

Thank you again for sharing your story. Such a personal experience helps demonstrates what a difference involving families can make.

Best wishes,

Daisy

Thank you for your insight and expertise into involving the family in therapy. I too feel that involving the family in therapy is a key factor for successful outcomes and acceptance within the family. I am currently a graduate student working in an elementary school. The school I work at doesn’t always have parents who are extremely supportive of school activities, which I”m sure is the case at most schools. I was wondering if you had any suggestions on how to involve parents and families who want to be involved in therapy as little as possible?

Dear Krista,

Thank you for your kind feedback. Of course this can be a challenge! Parents are busy, have multiple demands on their time and resources, and practically getting to sessions etc can be difficult.

Here, the therapy process starts with an in depth parent ‘interview’ or case history – often several hours long. From involving them in the process in such depth from the beginning, the value placed on their input is made very evident. We also use a multifactorial framework to help parents to understand how important support from the child’s environment is in relation to fluency and development of communication skills. This helps parents to really understand the rationale behind their involvement. Once they understand this, typically parents can see how the effectiveness of therapy can only be enhanced by them being involved.

We also set out clear expectations from the beginning, that both parents attend all appointments within a 2 parent family and provide a space for parents to problem solve how they can make this work when this presents challenges. We would often suggest postponing therapy to allow both parents to attend, for example if one parent needs to give more notice to their employers.

Another thing that I think helps is delivering therapy in a way which reinforces what parents are doing well, rather than telling them what they ‘should’ or ‘ought’ to be doing differently. They then feel encouraged, empowered and more confident about their own ability to support their child – and then perhaps more motivated to be involved.

I hope this helps.

Best wishes,

Daisy

Our Post: Hi Daisy! This was a great reminder to include school-age children’s parents in their therapy. Speech therapy in school only can be a bit isolating for parents, and I agree that providing a therapeutic space for parents to speak their minds would be beneficial concerning therapeutic outcomes for the children. What might be a few other ways you would recommend to better include parents in the therapy itself (e.g. keep them updated on weekly therapy activities/progress/participation) and increase parents’ ability to implement home practice?

Hi there,

Thank you for getting in touch. Yes I agree, having previously worked in schools in my last job this can be a real challenge. I suppose at the centre we advocate working in quite a different way – working primarily with parents (even if the sessions themselves are in schools). However, as is often the case, service demands can make this model of working challenging.

My response to the post above may be helpful in establishing that initial contact with parents. However, within a school-based model, absolutely your suggestion of keeping them updated on a weekly basis sounds sensible. Perhaps running a parents group session(s), or drop-ins could help you to start building relationships with parents and developing their understanding about their role in the therapy process. You could invite them along to attend as many sessions as they can, and set the child explicit homework tasks requiring them to share aspects of the therapy. Parents often say that it is really hard for them to know how to do the practice with children unless they have been involved in the sessions. If working on strategies they can feel very unsure about how/if to prompt their child, respond to their child’s stammering, or moments when their child speaks fluently… these can be invaluable conversations to have with the child in the presence of their parents.

We also find that sessions via Skype or Facetime etc. can allow parents to access sessions when they would be otherwise unable to.

I hope this helps.

Daisy

I agree with all of your (well-researched) points. I believe involving a child’s therapy is beneficial no matter the disorder, but especially with stuttering. There is a huge counseling piece that is necessary. I think asking the parents those questions and having a discussion about their thoughts will make them feel empowered. Additionally, it can help them understand how their reactions may influence their child. The visual representations of the cycles may bring awareness to them.

One question: what if the parent is not willing to participate? What if the parent is not willing to listen?

Hello,

Thank you for your response. I would absolutely agree that this applies way beyond stuttering therapy, and yes counselling is a huge part of the process.

Perhaps my response to Krista a few comments up may help with your questions. Parents can find it hard to engage in therapy sometimes – and for many different reasons; practical e.g. childcare, work…; emotionally finding it challenging; parents who stammer come with their own experience of therapy; parents may have had less helpful experiences of speech therapy in the past… Understanding what is getting in the way for a particular parent is probably the first step. We’d tend to ask parents that exact question – ‘what’s getting in the way?’. We can then explore that with them and support them to come up with ways to make it work. If there is something we are doing in the way we are working that is not fitting for them, we can also adjust. We might also explore whether it is the right time for therapy e.g. if they are moving house, new schools, new baby etc etc, chances are there will also be a lot going on for the child. Sometimes waiting for the right time will be most helpful.

With willingness to listen, the role of the therapist can become much more of a facilitator rather than ‘teacher’ – so therapy provides a space for parents to come up with ideas about what helps. The therapist is then in the position of asking questions, listening and reinforcing. Because the ideas have come from the parents, they will be things that fit with their family, their culture, their way of doing things – so they will be much more likely to be able to implement them. It also takes the pressure off as the therapist – we don’t need to have all the answers!

I hope you find this useful, please feel free to ask further questions.

Best wishes,

Daisy

Hello Daisy,

I like the idea of including the thoughts and feelings of parents who stutter themselves in session. I am currently playing around with the idea of starting conversations about stuttering openly with parents first in order to model and warm the child up to the idea of speaking openly about their experiences as a CWS.

As you discussed, parents who stutter themselves may have negative experiences, such as being bullied, and we need to validate their thoughts and feelings. During “automatic negative thoughts” tasks, do you find it beneficial to speak with the parents without the child present first? I was thinking of parents who may be more hesitant to share negative reactions with the child present.

I love the idea of connecting the cycles of the parent and child to create the “bowtie”. It would be a nice way to show the child that he or she can have these conversations with the parent since they share similar experiences.

Thank you for a wonderful read!

Hi there,

Thank you I am glad you found it useful.

As mentioned in previous posts, we always start with a parent-only consultation. This gives all parents (not just those who stutter) a chance to speak openly about their thoughts and feelings relating to stuttering. We might also return to a parent-only session or two throughout therapy should it feel like parents need more time to explore this without their child present.

I hope this clarifies.

Best wishes,

Daisy

Hi Daisy,

I enjoyed reading your paper. It is easy to forget about the family sometimes. Do you have any advice on how to talk to parents who have unrealistic ideas about the purpose of therapy and what it can accomplish?

Dear Elaine,

Thank you for your reply. Getting a balance between maintaining ‘hope’ and managing expectations can be tricky. Exploring parents ‘best hopes’ from therapy (what they want to get out of it) is a helpful starting point. If their ‘best hope’ is that their child will be fluent or the stuttering will go (as it often can be), then exploring what difference that will make for them can be helpful (e.g. they’ll be more confident, speaking more, we will be less worried about them starting their new school…). This is from a solution focussed brief therapy approach.

With school age children, the message is typically that the aim of therapy is not to ‘cure’ stuttering, but we know we can help children to reach their potential, have strategies to manage their speech and reduce the impact of stuttering on them day to day.

Thanks again and best wishes,

Daisy

I really appreciated how you outlined some of the struggles that parents of children who stutter may be going through. While this paper focused on the numerous benefits of involving parents in their child’s therapy, I wondered if you had any thoughts or knowledge of support groups for parents of children who stutter. Your paper really made me think about the potential benefits of a supportive group for these parents. It would also seem like a good opportunity to build a community and share information. A quick search yielded no results for me, so I wondered if you knew of any support groups like this, or what your thoughts were on the possible benefits it could provide.

Hi there,

Thank you for getting in touch. Support groups for parents of children who stutter can be so powerful! When run a group therapy programme for children aged between 10 and 14, and alongside the children’s group parents also attend a parents group. They are as involved in the therapy process as the children and attend for the full duration of the course. Parents have said that meeting other parents who have experienced the same challenges and emotions has them can be such a relief. They can become a real source of support for each other, and in turn increase the emotional resources they have for supporting their children.

I’m not sure where you are based, but perhaps local stuttering charities or speech and language therapy services may be aware of existing parent support networks. If not, perhaps organising parent workshops for parents of children on your caseload or signposting parents to larger online forums such as the British Stammering Association, see: https://www.stammering.org/help-information/parents/school-children/social-media-and-self-help-groups-parents

I hope this helps.

Daisy

Hi Daisy,

Thanks for submitting this fine paper and for highlighting the importance of investing in parent and family relationships. Your concluding paragraph is going up on my bulletin board, and I’m planning to share your paper with all of my colleagues in my school district. Keep up the good work.

Rob Dellinger

Rob, thank you for your kind words. It is great to hear that you plan to pass on the message to colleagues, the more therapists involving parents the better!

Daisy

Hi Daisy,

My name is Olivia and I am taking an advanced fluency course at the University of Minnesota-Duluth. After reading your articule, I am wondering how you would draw the line between the session’s goal being to support the child and family and focus on the child’s stuttering, and the parents taking over the session with their concerns and it end up being a counseling session for the parents? Obviously counseling is important in the situation, but it isn’t in an SLP’s scope of practice to be doing family counseling.

Thanks!

Hi Olivia, thank you for getting in touch. This is clearly an important consideration and you are absolutely right that it is important that we are working within our professional boundaries and personal competencies. If issues brought to us by a family are clearly beyond the scope of the SLP (e.g. relationship difficulties between parents, significant difficulties managing behaviour, psychological issues or emotional difficulties which are severe or not related to stammering) it is important that this is made clear to parents and the child where appropriate, and support from other professionals is sought.

Given the emotional aspect of stuttering for children and their parents, additional training in psychological approaches or counselling is extremely helpful for a therapist specialising in this area. Sessions may start with joint agenda setting between the child, parents and therapist. This can help structure sessions, and help the therapist keep the session ‘on topic’. Should something come up that feels important for parents to talk about in more detail, this could be returned to in another, perhaps parent only, session. Obviously the needs of the child who stutters must remain the priority, however I would suggest that should parents be feeling more at ease with stuttering, this can be enormously helpful for the child.

I hope this helps, I’m sorry my answer could not be more straightforwards.

Best wishes,

Daisy

Daisy

My name is Jamie and I am a 2nd year graduate student (speech-language pathology) at the University of MN – Duluth. I really enjoyed reading your post and learning more about the importance of engaging families in therapy. I will take away the benefits from your work and apply them to my clinical internships. As you know, with any communication disorder, parental involvement can be extremely beneficial. What is your advice when the parental involvement isn’t beneficial to the child’s success?

Thanks for your time

Jamie

Dear Jamie,

Thank you for getting in touch with your question. I am pleased that you are planning to involve families during your internships. Your question is a tough one… Initially my thoughts are that if parental involvement in therapy (or more generally) does not appear to be beneficial to the child, then even more reason to engage the parents and help them support in a constructive way.

In my experience parents want to do their best to help. Some, for many different reasons may end up doing things that may not be considered beneficial either by the child or from the perspective of a therapist. By providing parents with information, an opportunity to be heard and reflect on how they can support, their confidence in their ability to help their child can increase, and they can start to have conversations with their child about how to help. In the vast majority of cases, the benefits of having parents involved will greatly outweigh the disadvantages.

In rare cases (e.g. neglect or abuse), clearly another key adult/ caregiver may be the most appropriate person to be involved in therapy, although this applies to a tiny minority of cases.

I hope this helps, and I hope I interpreted your question correctly. If not please do let me know.

Daisy

Hi Daisy,

Thank you for sharing! Do you find it difficult to involve parents at the beginning of therapy for school-age children if their services are only in the schools? There is more limited contact to some degree compared to a private practice, so I was curious about your take on that.

Thanks,

Stephanie

Hi Stephanie,

The Michael Palin Centre is more of a ‘clinic’ or therapy centre, and we are not based in schools. We run training for SLTs/SLPs, many of whom are schools-based. They often comment that it can be harder to have contact with parents within this model and I agree, having previously worked in schools in my last job this can be a real challenge.

Having said that, there may be ways to involve parents that would work within your service e.g. running parent workshops, inviting them into school for sessions, offering parent session via Skype or running courses within school holidays for parents and children. Once contact has been made and you have formed a relationship with parents, should your work with the child continue within school keeping regular updates going via email or telephone could help them stay in the loop, and up to date as to how to support their child.

Thanks and best wishes,

Daisy

Hello Ms. Hope,

I enjoyed your paper, and appreciate the link you shared in another comment and all these great references.

Could you described what a typical session looks like within this approach? Also, another paper presented in this conference spoke to the benefits of involving a mental health professional in therapy for people who stutter- do you believe such involvement could augment this approach?

Thank you for your time,

Blaine

Dear Blaine,

Thank you for getting in touch. It is hard to give a description of what a typical session may look like. A typical session outline in the early stages of therapy may include:

– parents and child listing things they had been pleased to notice that week

– discussion on a topic e.g. what makes a good communicator

– watching back videos of the child and parent(s) playing or interacting, then encouraging them to identify their strengths and a target.

– negotiating parent responses to stammering and fluent speech

We are in the process of constructing a manual for working with this age group so look out for that (Palin Stammering Therapy for Children).

As I mentioned in a previous post, if the mental health needs of a client are more severe or not related to their stuttering then absolutely seeking additional professional support in advised. At the Centre, we all have some additional training in psychological approaches to help us to manage the emotional and psychological aspects of stammering.

Thanks again and best wishes,

Daisy

Hi Daisy,

Thank you for sharing such wonderful insights about involving parents in therapy for school age children who stutter. I used to be a teacher for children with special needs and I always believed that in order to make a difference, families, teachers, and therapist must work together. We all see the child in a different setting and can bring so much more to the table if there is a comfortable and safe environment to do this. However, one problem I often faced when teaching was working in schools that were located in low socioeconomic neighborhoods. I often found that parents could not make it to meetings, where information about their child and the plans/goals to work with the child were discussed, due to work or other obligations that impacted their ability to attend the meetings. We would often try to call and complete a telephone conference, but very rarely could these occur as well. I was wondering what your insight is on being able to give these parents, whose children are receiving services in schools,the opportunity to be involved in the therapy/meetings. Would it be reasonable to hold seminars or parent nights where these parents may be able to attend and learn about ways they can help their child? What about daily or weekly logs that allow parents and therapist to communicate in a way other than face-to-face?

I believe in the saying that it takes a village to raise a child, and I believe that it is vital for a child’s success to have communication, support, and involvement from all individuals who are involved in the child’s life. Finding ways that can allow this to happen for all children would be a wonderful tool to have.

Thanks again,

Callie

Dear Callie,

Thank you for getting in touch. There have been a few posts now about how to engage families when based in schools. It sounds like as far as you can you are doing your best to engage some pretty hard to reach families and have lots of ideas about how you go about this. When families have additional pressures (children with disabilities, financial issues, housing problems etc), certainly prioritising fluency therapy can be hard.

Your ideas about having meetings or parent nights in school, using email or logs to keep in touch sound great. There is typically no ‘one size fits all’, as I’m sure you know, and maybe individual discussions with families about what would work for them may be most helpful. Asking a family ‘what got in the way?’ when they have been unable to make a session or telephone appointment can be a good place to start in finding out more about the barriers for them.

Good luck! It’s not easy but it sounds like you are really determined to help the children you work with reach their potential and to support their families and communities too.

Best wishes,

Daisy

Hello Daisy!

I found this paper intriguing as you talked about a different side to stuttering, I believe this to be a part of the backstage of what is going on. I admire your integrity and your passion about this topic for I also possess this sense of needed support around children who stutter. I believe the assistance from a parent is a rather strong stepping stone and provides therapists with insight on how the treatment will go knowing the parent will be actively involved. My question for you is, What would you say if the parent is not willing to work with their child because they do not believe there is anything wrong?

Dear Orion,

Thank you for getting in touch and for your kind feedback. Of course there are times when parents do not see stuttering as a problem and therefore do not see therapy as being a priority. By the time a child reaches school age, most are able to tell us about their own experience of stuttering and their desire (or otherwise) for any help with it. If both the child and the parent do not believe anything is wrong, i.e. do not see stuttering as a problem, then neither should we, and most likely no therapy is indicated.

In my experience, it is rare for a parent believe that nothing is wrong if their child is having a hard time with their speech. However, if a parent is unaware of the impact that stuttering has on their child, part of our role may be advocating for the child and helping parents to understand how they can help their child further. Developing a culture of increased openness within such a family may be one of the things we focus on within therapy.

I hope this goes some way to answering your question.

Daisy