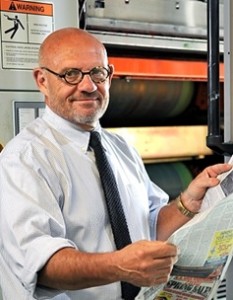

About the author: Vince Vawter, 67, retired after a 40-year career in newspapers, most recently as the president and publisher of the Evansville (IN) Courier & Press. Vawter’s debut novel, Paperboy, was published this year by Penguin Random House. The story deals with an 11-year-old boy with a debilitating stutter who takes on a friend’s newspaper route in a 1950s Memphis only to find racism, violence and, eventually, hope. The book is a selection of the Junior Library Guild and numerous other literary groups. Vawter lives with his wife of 41 years on a small farm in Louisville, Tennessee, in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains. About the author: Vince Vawter, 67, retired after a 40-year career in newspapers, most recently as the president and publisher of the Evansville (IN) Courier & Press. Vawter’s debut novel, Paperboy, was published this year by Penguin Random House. The story deals with an 11-year-old boy with a debilitating stutter who takes on a friend’s newspaper route in a 1950s Memphis only to find racism, violence and, eventually, hope. The book is a selection of the Junior Library Guild and numerous other literary groups. Vawter lives with his wife of 41 years on a small farm in Louisville, Tennessee, in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains. |

As a 67-year-old person who stutters and as a veteran of numerous speech-therapy protocols, I sense a critical change has taken place in the stuttering community. It’s a delicate subject, but one that demands exploration.

It seems to me that “finding one’s voice” is becoming a more strategic goal than “clinical fluency.” If this is true, I shout “Hallelujah” from the rooftops.

This paradigm shift I sense might be too heavily weighted by my personal experience, so I invite speech professionals and PWS to challenge my views.

The cynic asks: Whatever do you mean by “finding one’s voice?”

I’ll try to explain. “Fluency” is a condition that is not finite. “Finite” means “having definite or definable limits.” The average speaking rate for those who don’t stutter is calculated to be 167 words a minute while the rate for those who do stutter is 123 words a minute. What happens if you hit 145 words a minute? Are you half fluent?

I describe “finding one’s voice” as acquiring the verbal skills to voice any sounds or words in any setting with some degree of confidence and comfort.

I found my voice. I did not find fluency.

To make the matter more complex, I know several people who identify themselves as persons who stutter, but they never or rarely have discernible disfluencies. Yet, I understand the need for this label. I have on rare occasions – and I do mean rare – announced my stutter and then gotten through a speech or formal presentation with only slight disfluencies. “But you don’t stutter,” the listener will offer with a quizzical look. I usually respond with the allegory of the swimming duck; I may seem calm on top, but I’m paddling like crazy below the surface.

Is this new mindset a capitulation that stuttering cannot be overcome and that speech therapy is fruitless? Absolutely not. This new way of looking at stuttering makes treatment with trained professionals more important than ever. Stuttering is a complex journey and should never be attempted alone.

Let’s pause here for a word to parents. Let your child and his/her speech therapist set the goals for therapy until the client is of age to determine the goal as an individual.

A part of finding one’s voice is simply discovering what works. Everyone’s path to his or her voice will be different. I urge everyone to be wary of one-size-fits-all treatments.

While I use many of the techniques I learned in therapy, I also choose to violate “the rules” if I feel so inclined. It’s all a part of a newfound freedom. For instance, I substitute words and sounds in daily conversations like nobody’s business. I have maybe a hundred different ways to answer the phone. My favorite is “Howdy Doody.” (That happens to work wonders with telemarketers.)

Does anyone really care if I say “prior to” rather than blocking on “before”? If they do, they have the problem and not me.

I occasionally sneak up on problematic sounds like a cat burglar. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. Unlike a burglar, I don’t care much if I get caught.

Humor is my fail-safe after unusually long blocks or in formal situations. (“That’s easy for me to say” or “If you have a couple of hours, I can repeat that.”) One of my favorite ways to start a book reading is: “I have some good news and some bad news. The good news is I’m only going to read a couple of pages. The bad news is, we could be here all night.” Ba-da-bum.

I don’t do any therapeutic voluntary stuttering. I just stutter . . . and pretend that it counts.

Obviously, this raises the question of whether or not all my time, energy and money spent on speech therapy has value. Most certainly there is value. I found my voice because I searched hard for it and never gave up. I earned it.

Another dramatic change I’ve noticed is that we who stutter flock to each other now instead of existing on our lonely islands. Many wonderful organizations stand by waiting to help us. Social media permits us to connect with each other non-verbally, but we also listen to stuttering podcasts like crazy and we party-down together at conventions like never before.

I recently spoke at the American convention of FRIENDS (The National Association of Young People Who Stutter). I’ve never experienced a more sincere, loving and hard-working group of young people and parents. Many of the families had attended every convention for the past 16 years. I was honored to be in their presence.

David Mitchell, one of the finest novelists of the 21st Century, had this to say this summer in The Netherlands at the 10th World Congress for People Who Stutter: “If life is a journey from some kind of ignorance to some kind of enlightenment, then some kind of disability is a head start, and that has value.”

I should stop right here because I don’t have anything to top that.

My only regret on my long journey is that I courted that fickle mistress called fluency for too long instead of simply searching for a voice with which I was comfortable. If fluency sounds unnatural, it doesn’t work.

I spent many months writing and rewriting the ending to my young adult novel, “Paperboy,” that tells of an 11-year-old boy fighting a crippling stutter in 1959 in a racially segregated Memphis. I was insistent with my editors that I could not let my story dissolve with a fairy-tale ending. I wanted the boy’s humanity to lift him above the struggle. The story is one of triumph, not of fluency.

In closing, I share what I like to call my three-part Stuttering Manifesto, developed over 60 years of study, determination and, finally, contentment:

- Stuttering is what we do when we try not to stutter.

- Stuttering is not cured, but overcome.

- Fluency is overrated.

A PERSONAL NOTE TO JUDY KUSTER

This paper would not be complete without a huge THANK YOU to Judy Kuster who has managed the ISAD Online Conference for so many years. Judy has always amazed me with her knowledge and work ethic. With all her many irons in the fire, she has never failed to answer an email or phone call promptly (even while on vacation) and she always gives more than is asked. Judy, the ISAD Online Conference will miss you, but we know you will always be with us.

![]()

Hello Vince,

Your truthful and humorous approach to stuttering livens up the room. I couldn’t help but laugh at your jokes about your stuttering experience. It’s evident that you have embraced your life as a whole and not related on “fluency” as a measure of well-being. Well done. I am encouraged and entertained by your raw nature and realistic view of the importance of life. As a third-grade teacher, I do weekly “fluency” screening in my classroom. In order to be considered grade level, each child must meet a certain benchmark words-per-minute (WPM) in the fall, winter, and spring. As you enlightened readers in your story, how do we know a certain WPM truly is a measure of fluency? I agree with your stance. I have children in my classroom who can read 150+ WPM, but can’t tell you the name of the main character. On the contrary, I have seen children who read 70 WPM, but can recall, and re-tell, all the main details. It’s intriguing, really. To bring light on your statement about substituting certain words in order to avoid stuttering, I think that’s genius. As we move into the common core standards in education, one of the evident factors of knowledge is the ability to answer computer-based exam questions powerfully through a written message. Thus, the ability to manipulate words and phrases is essential to practice in both verbal and non-verbal communication.

Marika R

ISU SLP Graduate Student

Thank you, Marika.

You provided new insight for me. I am continually blathering on about SLPs looking at their clients in a holistic way, but I never say much about PWS looking at their life “as a whole.” Thank you for that. PWS must take responsibility in their search for voice.

You have forced me to reveal something that may sound strange to some, but it helped me come around to my concept of finding one’s voice. On of my “pastimes” for many years was to take a seat in a coffeehouse or some public place and listen to conversations of others. (While my speech might have been judged deficient, I had excellent hearing in my younger years!) I would actually grade the viability of the conversation as to content, clarity and practicality. For instance, a routine gossip fest would receive a 1 and a discussion of religion or a DIY project might receive a 10. I never came up with an average, but it surely was no higher than a 5, and probably was closer to a 2 or 3. I’m not sure what led me to do this, but it helped me gain traction in my believe that what you say is more important than how you say it. That theme is recurrent in my book.

And so, Marika Pittman, I give you a 10 for your comments today!

Vince,

This is a great article! As an aspiring SLP this outlook on stuttering was very refreshing to hear! It was great to hear your take on stuttering and fluency from decades of personal experience. It often seems that in a textbook you are fed the idea of how to achieve a reduction of stutter-like disfluencies, and that the focus is on helping the client achieve their best possible verbal communication, without ever much thought being put into how the client feels about their stuttering. It often seems that the goal is to alter the communication without first looking at the communicator. So thank you for your perspective on the shifting views of those who stutter, and as a future SLP, thank you for inspiring me to consider these ideas of “finding one’s voice”, instead of finding the “best” voice.

Thank you, pmatenaer.

Perhaps Stephen Covey said it best in Habit 5: “Seek first to understand, and then to be understood.”

Wow, this will be a great asset for everyone to apply into their techniques went treating PWS. I am learning about this very thing in my fluency class and had a speaker come in just the other day and talk about this very thing. About accepting it and running with it, instead of trying to run away. I love the quote above by Stephen Covey and when I am done with school, I will definitely apply this to my therapy approaches. Thanks for posting!!!

Trae P

ISU Graduate Student

Hi David,

I’m delighted that you have finally found your voice. Like you, I’m finding it SOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO liberating. 🙂

You wrote:

“Everyone’s path to his or her voice will be different.”

I wholeheartedly agree. The paths that we tread are influenced by many different factors. We are all unique – we come from different backgrounds/cultures; have encountered different life experiences; are affected by different doubts and fears; and possess different aspirations. We also commence from different starting lines and operate in accordance with different values and belief systems. That is why we should never attempt to compare our progress with others, nor be surprised when someone else decides to tread a contrasting or less conventional path.

Kindest regards

Alan