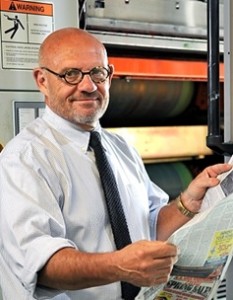

About the author: Vince Vawter, 67, retired after a 40-year career in newspapers, most recently as the president and publisher of the Evansville (IN) Courier & Press. Vawter’s debut novel, Paperboy, was published this year by Penguin Random House. The story deals with an 11-year-old boy with a debilitating stutter who takes on a friend’s newspaper route in a 1950s Memphis only to find racism, violence and, eventually, hope. The book is a selection of the Junior Library Guild and numerous other literary groups. Vawter lives with his wife of 41 years on a small farm in Louisville, Tennessee, in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains. About the author: Vince Vawter, 67, retired after a 40-year career in newspapers, most recently as the president and publisher of the Evansville (IN) Courier & Press. Vawter’s debut novel, Paperboy, was published this year by Penguin Random House. The story deals with an 11-year-old boy with a debilitating stutter who takes on a friend’s newspaper route in a 1950s Memphis only to find racism, violence and, eventually, hope. The book is a selection of the Junior Library Guild and numerous other literary groups. Vawter lives with his wife of 41 years on a small farm in Louisville, Tennessee, in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains. |

As a 67-year-old person who stutters and as a veteran of numerous speech-therapy protocols, I sense a critical change has taken place in the stuttering community. It’s a delicate subject, but one that demands exploration.

It seems to me that “finding one’s voice” is becoming a more strategic goal than “clinical fluency.” If this is true, I shout “Hallelujah” from the rooftops.

This paradigm shift I sense might be too heavily weighted by my personal experience, so I invite speech professionals and PWS to challenge my views.

The cynic asks: Whatever do you mean by “finding one’s voice?”

I’ll try to explain. “Fluency” is a condition that is not finite. “Finite” means “having definite or definable limits.” The average speaking rate for those who don’t stutter is calculated to be 167 words a minute while the rate for those who do stutter is 123 words a minute. What happens if you hit 145 words a minute? Are you half fluent?

I describe “finding one’s voice” as acquiring the verbal skills to voice any sounds or words in any setting with some degree of confidence and comfort.

I found my voice. I did not find fluency.

To make the matter more complex, I know several people who identify themselves as persons who stutter, but they never or rarely have discernible disfluencies. Yet, I understand the need for this label. I have on rare occasions – and I do mean rare – announced my stutter and then gotten through a speech or formal presentation with only slight disfluencies. “But you don’t stutter,” the listener will offer with a quizzical look. I usually respond with the allegory of the swimming duck; I may seem calm on top, but I’m paddling like crazy below the surface.

Is this new mindset a capitulation that stuttering cannot be overcome and that speech therapy is fruitless? Absolutely not. This new way of looking at stuttering makes treatment with trained professionals more important than ever. Stuttering is a complex journey and should never be attempted alone.

Let’s pause here for a word to parents. Let your child and his/her speech therapist set the goals for therapy until the client is of age to determine the goal as an individual.

A part of finding one’s voice is simply discovering what works. Everyone’s path to his or her voice will be different. I urge everyone to be wary of one-size-fits-all treatments.

While I use many of the techniques I learned in therapy, I also choose to violate “the rules” if I feel so inclined. It’s all a part of a newfound freedom. For instance, I substitute words and sounds in daily conversations like nobody’s business. I have maybe a hundred different ways to answer the phone. My favorite is “Howdy Doody.” (That happens to work wonders with telemarketers.)

Does anyone really care if I say “prior to” rather than blocking on “before”? If they do, they have the problem and not me.

I occasionally sneak up on problematic sounds like a cat burglar. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. Unlike a burglar, I don’t care much if I get caught.

Humor is my fail-safe after unusually long blocks or in formal situations. (“That’s easy for me to say” or “If you have a couple of hours, I can repeat that.”) One of my favorite ways to start a book reading is: “I have some good news and some bad news. The good news is I’m only going to read a couple of pages. The bad news is, we could be here all night.” Ba-da-bum.

I don’t do any therapeutic voluntary stuttering. I just stutter . . . and pretend that it counts.

Obviously, this raises the question of whether or not all my time, energy and money spent on speech therapy has value. Most certainly there is value. I found my voice because I searched hard for it and never gave up. I earned it.

Another dramatic change I’ve noticed is that we who stutter flock to each other now instead of existing on our lonely islands. Many wonderful organizations stand by waiting to help us. Social media permits us to connect with each other non-verbally, but we also listen to stuttering podcasts like crazy and we party-down together at conventions like never before.

I recently spoke at the American convention of FRIENDS (The National Association of Young People Who Stutter). I’ve never experienced a more sincere, loving and hard-working group of young people and parents. Many of the families had attended every convention for the past 16 years. I was honored to be in their presence.

David Mitchell, one of the finest novelists of the 21st Century, had this to say this summer in The Netherlands at the 10th World Congress for People Who Stutter: “If life is a journey from some kind of ignorance to some kind of enlightenment, then some kind of disability is a head start, and that has value.”

I should stop right here because I don’t have anything to top that.

My only regret on my long journey is that I courted that fickle mistress called fluency for too long instead of simply searching for a voice with which I was comfortable. If fluency sounds unnatural, it doesn’t work.

I spent many months writing and rewriting the ending to my young adult novel, “Paperboy,” that tells of an 11-year-old boy fighting a crippling stutter in 1959 in a racially segregated Memphis. I was insistent with my editors that I could not let my story dissolve with a fairy-tale ending. I wanted the boy’s humanity to lift him above the struggle. The story is one of triumph, not of fluency.

In closing, I share what I like to call my three-part Stuttering Manifesto, developed over 60 years of study, determination and, finally, contentment:

- Stuttering is what we do when we try not to stutter.

- Stuttering is not cured, but overcome.

- Fluency is overrated.

A PERSONAL NOTE TO JUDY KUSTER

This paper would not be complete without a huge THANK YOU to Judy Kuster who has managed the ISAD Online Conference for so many years. Judy has always amazed me with her knowledge and work ethic. With all her many irons in the fire, she has never failed to answer an email or phone call promptly (even while on vacation) and she always gives more than is asked. Judy, the ISAD Online Conference will miss you, but we know you will always be with us.

![]()

Vince, I truly enjoy your considerable gift with words and appreciate your kind note at the end of your contribution to this conference. You shared that you have been on a “long journey” where there was considerable “time, energy and money spent on speech therapy” during which you “courted that fickle mistress called fluency for too long instead of simply searching for a voice” with which you were comfortable. Was there an “aha” moment that led you to the conclusion to be comfortable with your own voice, whether is was fluent or not? Whenever that occurred, did that insight affect your level fluency either positively or negatively?

Judy, The “aha moment” I’m going to tell you about could not be classified as “cathartic,” but I do remember it well and it’s funny if nothing else. In 1988 I gave my first speech to a civic club. I had become fairly comfortable managing a newsroom, but I resisted public speaking. I knew I had to take the plunge, so I agreed to give a noon speech to a local civic club in Knoxville. I wrote and rewrote my speech. Practiced it over and over. Got to the venue one hour early. Finally, I stepped to the podium with my notes in my trembling hands. I started my speech and was wrestling mightily with my nerves. After a few minutes, I looked down from the podium to the front row, and one of the club members was sound to sleep with his head over to one side. He may have even been snoring. A smile came to my face. Here I was, dying a thousand deaths and worrying what people would think of my speech, and this guy was in Never, Never Land. It occurred to me at that moment that no one in the audience was really analyzing my speech. Every one has their own trials and tribulations with no time to worry about my blocks or repetitions. I have wanted to thank that gentlemen every since.

Hi, this is armina .. I’m 19 yrs. Old, I’m still studying,… I got stutter also, when I was a child until now. Mrs. Barbara help me last night, she explained about stuttering, also I shared my experience when I was. Stuttered in my lecture or oral report in our class, and on how they teased me, they don’t accept me who i am,because of my difficulty of my speech, I can’t utter some word that I want to say. Mrs. Dham inspired me, she gave me some advices on how to control my stuttering.. but now I want somebody to help me to cured my mild stuttering, I hope it will help me to be successful.. thank you, and thank you also to Mrs. Barbara Dham

Armina,

First, age 19 is one of the toughest times for those of us who stutter. I GUARANTEE that it gets better. I’m not a speech professional but I urge you to think these thoughts: I do not talk like everyone else, but what I have to say is important. I will work to find my voice. It may not be the voice of others, but it will serve me well. Never try to hide your stuttering. Face it, even flaunt it, and your singular voice will emerge. You will succeed.

Vince,

Hi, uuhhm sometimes I’m afraid to talk, infront of the crowd. I have anxiety that’s why,I don’t know what people think of me,, and also I don’t want to lose my friends, because of my stuttering.. 🙁

I challenge you to pick one of your friends and tell them you would like to talk to them about something personal. And then ask them what they think about the way you talk. I think you will be surprised at their answer. I bet they will say something like this: “Armina, I realize you don’t talk like most of us, but I never thought much about it. I’ve always thought it was just you and I never spent a lot of time thinking about it.” I was at a high school reunion recently and I asked many of my old friends that questions. That was their universal answer. You think about your speech a thousand times more than your friends do. They have their own issues to think about. They like you but they don’t have time to think about your speech. So you don’t think about so much either.

Okk , uhhm I will do that.. thanks for your advice mr. Vince… I hope they will understand me,, the why I talk with them..

Vince,

I am a speech professional, but I am not going to challenge your views… I agree with them. I think we as a field have long talked about “finding one’s voice” as more important than fluency. But in my opinion, it is only recently that more and more of us are actually walking the walk. Like you, I am hopeful and sing praise.

Hmm.. the only thing I might challenge a little is part of Part 2 of your Manifesto. I totally agree that stuttering is not cured, I’m not sure if (for me) if I have “overcome” my stuttering, or if I have learned to treat it with kindness, and therefore dispelled the power it had over me.

Kevin Eldridge

Good point, Kevin. Perhaps the fear of stuttering is what is actually overcome. I’m sure people get tired of me telling them that I’m a person who stutters, but I do it every chance I get. Maybe I should design a t-shirt that says: Yes, I stutter. Now let’s talk about something important.

Great idea for a shirt!

Kevin

Hi Kevin,

I am someone who stutterers. I have a paper here called Turn-Around Thinking.

I would agree that a majority of our stuttering goes away once we overcome the fear of stuttering. This is primarily because, our stuttering, especially if you’re a severe blocker with secondaries, is us fighting to get our words out. If we stop that fighting, because we’re no longer afraid of not being able to get the words out, it becomes easier to speak.

I believe a large part in overcoming our fear is changing our emotional habits. We often are afraid of a speaking situation because we are afraid of how we will feel after we finish speaking, and we’re afraid of that because we ourselves beat ourselves up, knit-pick on the negatives of a situation after we stutter. If we can find a way to change our feelings after we stutter, from negative to positive, we would be in a much better place the next time – as we can break the cycle of fear. I talk about this a bit in Turn-Around thinking. It is a very idealistic concept, as it takes a very powerful mind to be able to switch your thinking about something. (And I’m not saying I have been able to in every situation.) However, I think it is the key to overcoming the fear.

Look forward to your thoughts here.

Best,

Dhruv

Vince,

My name is Megan and I am currently a graduate student hoping to be a speech therapist one day. I like how you focus on “finding your voice” and I think that all of us whether we stutter or not can learn something from your story! You mentioned that speech therapy can help find what works for you. It can help find your voice and not necessarily fluency. I was just curious if there were any speech therapy techniques that did help you and what they were?

Megan,

Although I have tried everything from the dreaded Edinburgh Masker to Precision Fluency Shaping, I hesitate to recommend specific therapies. As people who stutter we are all different, and I think we must go about finding our voice in our individual ways, but always with the aid of speech professionals. I will say that the two-second syllables and gentle onset helped my “feel” fluency for a while. I was able to build on that on my own after I left the program. I have no doubt that a majority of people who stutter can be taught a form of fluency in the clinic. The problem is the transfer outside of the clinic to the real world. My admonition to therapists is to always treat the entire client, not just the stuttering part of the client. It’s much harder for you, but it’s what we need.

Vince,

I am also a graduate student currently studying to be a SLP. I found your paper to be very inspiring and like Megan appreciated your focus on the individual finding their voice. You commented above that you think individuals should find their voice “with the aid of speech professionals”. Correct me if i’m wrong, but I understand that your “aha” moment was while you were preforming a speech. Like you stated above, one of the hardest things with therapy is transferring what you’ve learned to the real world. As an up and coming SLP I would like to know if there are any specific activities that were beneficial to you in the real world, or that you think would be beneficial to others in order to help them in finding there own voice. I understand that different activities will be beneficial to the individual at hand, but I am curious to see what helped you.

Thank you,

Maddie

Hi! My name is Emily and I am currently in grad school to become an SLP. I really appreciate everything you wrote about and I feel like you further confirmed what my professor is teaching us. It is not only important to teach techniques, we must empower them to own their voice and positively alter their self perception. I was wondering if there is anything specific your speech therapist did to help you along your journey? Was there a moment with or without your speech therapist when you found your voice? Thank you so much.

Hi, Emily. I’m not sure there was a single moment, but more like a series of breakthroughs with my own psyche. I was not willing to challenge my fears when I was on my own as a teenager and a 20-something, but when my wife and I started our family I knew I would need to be a good provider. I began to think about more than just myself. Then, I found out I had something to say. I loved working at newspapers and I wanted to be a good employee and then a good manager and boss. I’m not sure how a therapist imparts the courage that a client needs to step outside the comfort zone, but this is definitely part of the holistic approach that is needed. Never underestimate the challenge you have taken on as a speech therapist. I’m sure it can be frustrating and tiring, but there are those out there who need you.

Hi Vince,

Thank you so much for your inspiring paper! I have been treating children and adults who stutter for 36 years. I feel that I have a sense of what people experience, but given that I don’t stutter–I can’t truly know. So, I rely on insights from people like you that I can pass onto my kids. I must say, I have added your advice to Armina to my growing list of wisdom: “I do not talk like everyone else, but what I have to say is important.” Thanks again!

Hi, Rita

I have just completed an 8-day, 1,800-mile book tour through four states. My inbox is full of emails from parents who are struggling to help a child find their voice. With communication growing even more important in this warp-speed world, I believe your profession is more valuable now than it ever has been. So thank you for your 36 years . . . and don’t stop now!

Vince I am your age and over the years have come to a similar conclusion as yourself. However, the real challenge is convincing youngsters desperately seeking a cure that finding their voice is better than fluency.

Exactly, Paul. I liken it to going to a golf pro and saying, “I’m going to take lessons from you and I expect to be breaking par after a year’s worth of training.” The muscle mechanics of speech are much more complex than a golf swing. This is why I think clinicians must treat their clients holistically. To continue the golf analogy, a good golf pro might tell his student: “You may not be breaking par when we’re through, but I will teach you how to feel comfortable hitting a golf ball and you will enjoy every round of golf you play.”

Hello, Vince.

Like a few others who have responded to you already, I too am training to be an SLP. I find it very inspiring that you have written a novel and have been on tour for it around a few states. Not everyone is brave enough to do this. It is also great to see that your novel features a child who stutters as a hero and possible role model! How did you come up with the idea for your book and what would you like children to get out of reading your book (message or moral)? Thank you! -Colby G.

Hi Colby,

After I retired from newspapers, I looked at every work of fiction that had a character who stuttered. I could find nothing where the writer delved into the mindset of the stutter. I truly believe that kind of book needed to be written. I thought about writing a memoir, but then decided that I could get closer to the “truth” with a work of fiction. The message: What you have to say is more important than how you say it. Your voice is unique. Never be ashamed of it.

Hello Vince!

I loved your article and all your analogies really helped me get a sense for what it is like for a PWS and the three-part manifesto at the end is something I will remember when working with clients of my own. I was wondering if your thoughts and feelings about stuttering stem more from your own experiences with stuttering or the experiences of you’ve seen in others?

Hello CKEIL,

Probably 95 percent from my own experiences and 5 percent from PWS whom I have met. I’ve come to realize that since we all stutter differently, there is a great probability that we will find our voices in different ways. That’s why I’m so hard on one-size-fits-all therapy programs, and the reason I took up the crusade for a holistic approach by speech clinicians.

Hi Vince,

My name is Meaghan and I am currently in graduate school for Speech-Language Pathology. I really enjoyed your post! You had mentioned that there are now a lot of resources for people who stutter as opposed to years ago. Support groups seem like a great option for people who stutter. I was wondering if you ever wish you were born during a time where you had more resources for stuttering, such as support groups. Or, are you happy that you were born during a time where people focused on dealing with a stutter personally or during individual therapy? Thank You! – Meaghan

I think the stuttering support groups are wonderful and have a lot to do with the progress made in the field of speech pathology. When I was growing up, these groups did not exist. I never knew anyone else who had a difficulty like mine. We were each on our own little islands. I remember leaving therapy one day as a child and a boy about my age was in the waiting room. We looked at each other, and I’m sure each of us was asking ourselves: “Does he stutter like I do?”

Hi Vince!

I really enjoyed reading your article! I am a graduate student at Idaho State University, studying to be an SLP. We have recently studied the theories of stuttering and after going through countless ideas of the “whys” and “how to fix-its,” I feel very strongly that working on the emotional aspects of stuttering are even more important than helping a person who stutters become “fluent.” I can’t imagine the anxiety one must feel when they are pressured into fluent speech by tricks and techniques. I appreciate your view on therapy and I agree that fluency looks different for each individual.

I understand that there is an inherent danger in beginning therapy with a PWS and telling that person that they might not sound like other people when all is said and done. That’s what makes your profession so delicate and challenging. And we should never discount the fact that there will be folks like John Stossel and James Earl Jones out there. More power to them. When I speak to young people who stutter, I always quote one of the great philosophers of my generation: “You can’t always get what you want, but if you try some time, you just might find, you get what you need.” — Mick Jagger.

On the same note. If it has become general consensus that fluent speech is not the end goal of therapy, but rather speaking more comfortably is, then I’m puzzled as to why stuttering is still called a fluency disorder. If we are not chasing fluency anyway, why should that word/concept be part of the official title of the problem we have. Why not call it an “Occasional disfluency”? I know this still includes the word ‘fluent’, but by adding occasional we get closer to the real definition of stuttering. In that, it comes and goes – there are times when we are taking ‘normally’ and times when we get stuck. Or better yet, an “Occasional speech issue”. We get rid of the word fluent altogether.

Look forward to your thoughts on this.

Hi Dhruv,

I had not taken my thoughts that far, but maybe labeling is part of the problem. Should we call a speech therapist a “voice coach?” By the way, I’ve always preferred the term “speech-language pathologist” to “therapist” or “clinician.” The word “pathology” implies pathos and root causes rather than simply treatment.

I’m all for getting rid of the word “fluent.” I’ve known those who have magnificent vocalizations and say absolutely nothing. Voltaire said it best: “Speech was given to man to disguise his thoughts.”

Vince,

Thanks for sharing your journey toward finding your voice. As a professional, it is a privilege to be present for the journey, however it manifests itself for a particular person. You write that, “My only regret on my long journey is that I courted that fickle mistress called fluency for too long instead of simply searching for a voice with which I was comfortable.” Perhaps that is true. On the other hand, perhaps you searched for fluency until you were ready to look in a different direction. I’m not sure if there is a timeline that anyone ‘should’ or ‘ought to’ follow–I’ve noticed, as I’ve gotten older, that most of us tend to take another step or turn around and look at something a bit differently when we are good and ready.

Thanks for a lovely article!

Regards,

Lynne Shields

Lynne,

Very well said, and sometimes I probably get too “preachy” about finding one’s voice. I’m always careful to point out that I have no professional training, and that each person must find their own path — always with the help of a professional SLP. Once I slipped the surly bonds of dreading to hear my voice, I wanted to shout from the rooftops that I was no longer willing to let my speech control me. Of course, maturity plays a large part in that. After 67 years, I’m glad I learned something. Getting down off my high horse, what I would say now is take care of the children and give them some comfort as they wrestle with their speech goals. It may be tough, but it doesn’t have to be so lonely and confusing.

Vince,

I am so glad that you are speaking out about the importance of each person finding their own voice. You may help someone get to the point you’ve now reached sooner than they might otherwise have done on their own. Your message is such a positive one and coming from someone who has been through treatment may speak to those who are searching solely for fluency right now.

Thanks,

Lynne

Vince,

What you are saying makes sense to me! I am a SLP & a PWS. I fear that traditional therapy focuses too much on fluency and not taking clients how to stutter. Everyone stutters, some are notice and others are not. I used circumlocutions for many years and when I choose to stutter on the word I wanted to say, I found freedom. I love the idea of a paradigm shift, it is about time!!! “Finding one’s voice” is a beautiful way for PWS and SLP to think of communication.

Derek Taylor

The challenging part is to convey this message without letting anyone think we are “giving in” to a stutter. I liken it to golf. An infinitesimal number of humans can shoot par or better on a golf course. Does that mean we shouldn’t be out there hacking and whacking away and having fun? At one point in my life when I started doing a little public speaking, I would attempt to “score” my speech — bogey, double bogey, par, birdie. Now, I don’t keep score. I just swing away.

Perhaps only those of us who stutter can fully appreciate the difference in “fluency” and finding one’s voice. I don’t know why it took me so long to come to what I think is an obvious conclusion.

Vince –

I enjoyed reading your story! Thank you for sharing it!

As a PWS, I had all kinds of therapy as a kid and teen — Doman Delacato, Fluency Training/Shaping, Stuttering Modification, Hybrid of the two, DAF,and Drug Therapy. All of those “therapies” led to me choosing the ultimate stuttering behavior – Chosen Silence – by the time I was 17 years old. I hated stuttering, I hated talking & I hated interacting with others. Those “therapies” filled me with the fear of stuttering, the fear of talking and the fear of interacting with others. It was easier to just shut the hell up…Unfortunately, those fears were killing me inside as a person.

I did find a therapy and therapist at age 17 who helped me to deal with the fears and helped me to release the natural speech I had; the major therapeutic effect that helped me was developing a seemingly endless amount of IDGAS re: stuttering, talking and interacting with others.

I am soon to be 60. And this is what I know for sure about stuttering: Fearlessness goes a long way when it comes to stuttering, talking and engaging the world around me! I refuse to give in to any of the fear. I am gonna talk and say what I want to say no matter what!

Anyways, thanks again for sharing your story!

Retz

Retz, it sounds like you may be the long-lost brother I never had. I will see you all the therapies you mentioned and raise you an Edinburgh Masker! Have you ever heard of that devilish contraption? I suggested a few years ago that it could be used in place of water-boarding at Abu Ghraib. We came to our voices with hard work, the beating down of fears and probably a good dose of maturity. I don’t know how that can be translated to our children. If I could shake the hand of every SLP out there, I would. We survived, but now we must be sure the children are taken care of.

Vince –

Ah yes…The Masker! I use to participate in a support group, prior to the NSA, in the Evanston, Ill. area. A couple of Maskers tried to get me to use and endorse the usage of them. To me, they were just more BS stuff…Couldn’t do it. Waste of money, time and effort to me!

And yes – I believe completely that it the responsibility of we adults who stutter to educate the professionals having the honor of offering therapy to children who stutter – and their parents – a better therapy experience/outcome than we had as children and teenagers.

As one of those “kids” who stutter — Thanks for all you do Vince!

Hope to meet you one day!

Retz

Vince,

I am a graduate student for Speech Language Pathology and I am recently in a stuttering class. We learn about so many different techniques to try and make PWS’s disfluencies more fluent, however, the fluency never seems to be the main concern. The first step is accepting the stutter and embracing that it is a part of who you are. However, there are so many different techniques to avoid the stutter and only reinforce fluent speaking which is confusing for me. I love that making a stutter your own voice is an idea that is becoming popular in this field. The stutter will always be a part of who a person is and should be embraced. Although there are very valuable techniques to help stutterers become for fluent in order to communicate with peers, it is so important that they realize it will always be who they are and it’s wonderful!

I feel like I work with so many kids who are struggling with bullying and being pointed out as different, that this idea of “finding your own voice” should be part of therapy at a very young age. Thank you for this paper, I will use this advice in my future career!

Thanks. I believe the role of the SLP is more important now than at any time in the past. The difference between “fluency” and one’s voice is a difficult concept, especially for younger clients. Convince them the potential for their voice is unlimited, but that this may or may not have to do with a smooth delivery.

Vince, thanks for sharing. I was looking forward to hearing you speak at the FRIENDS conference this July, but was unable to make it – I had attended the previous 5 conferences, so was supremely disappointed to miss this year’s and your talk. I look forward to reading the book at some point.

I love the way you “tell it like it is.” I’ve reached that point in my life and stuttering career as well. I have “found my voice” after 30+ years of trying to hide my stuttering because I was ashamed and had early negative experiences ingrained in my head that stuttering was bad.

When I reached my 40’s, I said to hell with this and started letting the real me hang out, and haven’t looked back since. I did try therapy for two years, but it didn’t work for me, because I realized I didn’t want to be fixed – I wasn’t broken.

The student therapists were more interested in my fluency than I was.

I am one of those who produces a podcast about stuttering, but specifically to give women who stutter a voice, to tell their (our) stories. I also party hard at the stuttering conferences, since finding my first one in 2006. I regret it took me so long to kick down the door of my covert closet, but I’m letting nature run its course now.

I’ve learned to be comfortable (most of the time!!) with stuttering and I make room for it in my life. We co-exist peacefully now, instead of me always trying to deny it or push it away.

I talk to kids whenever I get the chance – both those who stutter and those who don’t – about living life, about compassion and about acceptance.

I’m glad you shared – what a great ISAD contribution.

Pam

Another great stuttering t-shirt: I’m not broke, so I don’t need fixing.

I love the thought of “making room” for stuttering in your life. That’s a great phase. Now, how do we explain this to our young folks? We earned our freedom after years of loneliness and confusion.

I wrote “Paperboy” to try to give some insight to this phenomenon of forgetting about stuttering and thinking about voice. If I can make one young life less lonely, I will consider the book a success.

Vince, what an inspirational paper!. Throughout my educational experience as a Speech Language Pathologist, I have read numerous papers on definitions, treatments, assessments etc.. about stuttering. It is not until now that I get a chance to learn about it from a different perspective, from a more human perspective! I hope that more people both professionals and clients would truly aim at finding “one’s voice”. I also like the fact that you talk about how this is a journey that should not be experienced alone. With the help of others who are having similar experiences and the help of professionals I can only imagine how much more enjoyable and helpful this journey becomes. Thank you for sharing your experiences and let’s hope that more people think about your ideas and implement them in their daily lives.

Maria Leon-Luciano.

Hi, Maria

As I said above, professionals like you are more important than ever. The concept of “finding one’s voice” is not easily assimilated into the psyche. Your work is valuable, but not easy. Good luck.

Hi Vince,

It was very uplifting to read your paper. I am a special education teacher who works with children on the autism spectrum, and also a graduate student in speech language pathology. The journey of “finding your voice” is also one I embark on with the students with autism whom I work with, and it struck me to notice parallels between my teaching experiences and your personal experience finding your voice. I think your message is powerful and important, not only for professionals who work with people who stutter, but for professionals who work with individuals with any type of communication challenge. I too feel that there is so much to be gained by treating the whole person, and by moving away from clinical approaches aimed to “cure a problem” towards individualized ones that aim to improve the quality of life for each individual by addressing their vast and unique needs.

Dear foodieslp,

You described my ultimate message much more eloquently than I could manage. Thank you.

Hello Vince:

Very interesting paper. Thank you for telling your story and professing your “manifesto.” You mention that it is hardest for young adults to “find their voice”. I wonder if you could comment on what role you think acceptance of and contentedness with ones life plays in one’s ability to “find their voice.” Also, could you please comment on the vicious circle effect whereby the trials and tribulations of “unsuccessful” life exacerbate stuttering thereby making it impossible to be successful either in life or in finding ones voice.

Michelle Paradies

Michelle, the holistic-type questions you ask are important — and TOUGH. Much later in my life I realized that probably what made me start the search for my voice in earnest was the fact I got married and started a family. I was not willing to confront my stutter just for myself. I didn’t have the courage. But when I realized that my wife and children were counting on me, I knew I had to stop playing games. The “vicious cycle” you talk about is real for people who stutter, but guess what — it can also cripple the most “fluent” of people. I blamed some of my failures in college (I went to four in six years) because of my speech. Looking back, I was using my speech as an excuse in some cases for outright laziness. Maybe my only legitimate gripe was the foreign language requirement.

I think this is one reason why “one’s voice” should replace “fluency” as a goal. PWS are so accustomed to “failing” that it becomes second nature. How can a person survive if they “fail” hundreds of times each day. I would challenge any client to access fully if their failings are absolutely connected to their speech. OK, if they want to be a news anchor, there could be a problem, but let’s be realistic. Most of humanity talks incessantly and says very little. Challenge your clients to make their voice count for something. That’s many times more important than beautifully articulated empty sentences which I call “sweet nothings.”

Vince,

I sincerely enjoyed reading this. I’m a second year graduate student and I feel that teaching any clients who stutter “to find their voice” is an excellent lesson. I’m currently in a fluency course right now and one of the topics that my professor has stressed is to help the client not be defined by their dysfluency; which I think you were able to convey very eloquently. Also, I was happy to read about how people are “flocking together” rather than distancing themselves from others and being on a “lonely island.” It’s encouraging to see more awareness and acceptance, as well as the progress being made. Thank you so much for this insightful paper!

Courtney

I am a person who stutters. I am a person who is bald. I am a person who could lose a few pounds. I am a person who doesn’t count his blessings enough. In short, I am a person.

Hi Vince,

I really enjoyed reading your “manifesto.” Its always refreshing to hear a real life story of someone successfully overcoming personal challenges.

I am currently a speech pathology student and I was wondering how you would advise clinicians to speak to parents about helping their child “find their own voice”? I would imagine that parents would be most concerned with “solving the problem.” So I was just wondering if you have had any experience with this issue, or have any advice?

Oh my! The questions keep getting tougher.

I can see how a “fluency-demanding” parent could be problematic. Here’s the reality. I take my son to a golf professional and say: “I’m going to turn over my child to you and you can have as long as it takes, but I want my child to be able to break par when you are finished.” The smart golf pro would say, “I can help your son improve his swing, and I can teach him how to enjoy the game, but there’s no way I can guarantee that he will ever break par.” As I said earlier, the small-muscle movements involved in articulation are many times more complex than the large muscles used in a golf swing.

I think if a parent could think everything through, what they want is for their child to be happy, well-adjusted and have a good opportunity for success in life. I contend that fluency, as defined by social norms, is not a prerequisite.

It may be more difficult teaching a parent the meaning of “finding one’s voice” than teaching the client. Eventually, the client will get it. I don’t know about the parents. I have seen some parents in the bleachers watching their children play sports that I’m sure would never get it.

Your profession, as fulfilling and important as it may be, will never be easy. Bless you.

Hi Vince,

Thank you for sharing your story. It is inspiring to others to hear about the challenges you’ve overcome. I am a graduate student studying speech-language pathology and after reading your paper I definitely agree that therapy should focus on “finding one’s voice” and not achieving fluency because this may cause frustration at achieving something that is so subjective. I had never considered the term of “finding one’s voice” and am definitely going to take on this way of thinking.

I enjoyed the analogy of the swimming duck, others do not know what is happening below the surface and as I have learned in fluency class, PWS have covert features that cannot be seen and that others may not understand. It is important to discuss emotions and what PWS think about their own stuttering. I also think it is important that a PWS should be able to determine their own therapy goals when they are old enough and they should be catered to their needs and what is important to them. Thank you again for your wonderful story, I have come away with many important points and different ways of thinking.

-Alicia

Hi Alicia,

This is a true story. When I was in my mid-50s and a newspaper editor, I was asked to come to a high school to critique the student newspaper. I didn’t have to give a speech and so I felt relaxed talking to the students about a subject I knew something about. We spent an entire class period talking about their paper. At the end I encouraged them to pursue journalism if that’s what they felt their calling to be. I then said that even though I was a person who stuttered, newspapering had been a rewarding career for me. As the students were leaving, one came up to me as asked why I said I stuttered. “Because I do,” I said. “You just can’t hear me sometimes.” She went on to say that her father was a person who stuttered and “it was really bad.” I corrected her and told her it really wasn’t “bad,” that it was just different from mine.

Hi Vince,

It is interesting to hear how others react to stuttering and how some individuals believe that stuttering is an “all-encompassing” term where in actuality, like every individual, variability exists. I believe that you definitely gave that individual something to think about when they left that day. Thank you for your reply.

Hi Vince,

Thank you for sharing your beliefs on stuttering. What a powerful message you have sent on “finding one’s voice” rather than achieving “clinical fluency”! As a future speech-language pathologist, I will never forget your words when working with people who stutter. Reading your story has been a great learning experience for me. As Alicia had posted previously, I also love your analogy of the swimming duck. Even though someone may have control of their stutter in that moment, does not mean they are not “paddling like crazy below”. Thanks again for your informative and inspiring words.

Jaclyn

Jaclyn, my duck analogy seems to have struck a chord. Please be aware that I’m not referring to the AFLAC duck. That particular duck drives me crazy.

Hello Vince,

I would first like to thank you for sharing your story. You have done a great service to the the speech-language pathology community as well as to PWS. In graduate school they often emphasize the importance of leading a client-centered practice, one that focuses on individuality. Your story epitomizes the reason why individuality is important. I enjoyed your explanation of “finding your voice” and agree that therapy should follow that concept.

Thanks Again,

Omar E. Alvarado

Graduate Student

NYC

Thanks, Omar. This non-sensical thought comes to me. PWS are individuals for sure, and perhaps we are more individual than most.

Hi Vince,

I really enjoyed reading your paper(it was written very good).

I think the reason why the therapists want treat fluency,is because they are fluent people.The pioneers of the field (that most of them stuttered)understood a long time ago,that stutterers dont need fluency but to find their voice,meaning to find a way to communicate despite the stuttering.I personally wanted to gain fluency cause i couldn’t speak at all ,my life changed when I found the way to stutter and still communicate.

Thanks

Ari

geashono@gmail.com

I’m right with you in shouting hallelujah! As a parent, I wanted to respond especially to your comment “Let’s pause here for a word to parents. Let your child and his/her speech therapist set the goals for therapy until the client is of age to determine the goal as an individual.” It’s so easy for the goal to become fluency, fueled by the continually demand for a decrease in disfluency counts (insurance, IEPs, even parents). I think parents need to 1) understand that reducing speech errors in the clinic setting is pretty meaningless and 2) the focus on reducing speech errors runs the risk of having the child chose silence over speaking. I think parents and speech therapists need to set appropriate goals (which I believe should focus on keeping them talking and engaged)and work together to make that happen. I believe putting parents in therapy to support this goal makes far more sense than putting children in therapy to fix their speech. What do you think?

I purchased “Paperboy” as an e-book and am finding it both heart-breaking and inspiring. I would love to get a hard-copy for my son. If you’re interested, I wrote “Voice Unearthed: Hope, Help, and a Wake-Up Call for the Parents of Children Who Stutter.” It’s available on Amazon and as an e-book, but if you contact me at voiceunearthed@gmail.com, maybe we can strike a deal to trade hard copies of our books? (I also wrote “The Right Time to Break Out the Stickers” for this conference.)

Love your sense of humor, your writing style, and your manifesto. Especially your manifesto…thank you so much for your work!

Best,

Dori Lenz Holte

Yes, Dori. I can see how fluency-demanding parents can be more problematic than parents who are non-invested in their children’s welfare. Do we open a can of worms when we ask SLPs to “treat” parents as well as the children? I’m not saying it shouldn’t be done, but I see land mines all around.

Hi Vince — I’m a little confused – I did not say (or even think) that fluency-demanding parents are more problematic than parents who are non-invested in their children’s welfare… and could you also explain to me what you see when you talk about land mines? Just curious…Thanks!

Dori

Ari, I believe that a person can be a good speech therapist whether or not they might have a stutter. Most professional and college football coaches (American football) weren’t superstars when they were playing. In fact, quite a few never played at the level they are coaching. In my opinion, the first thing a speech therapist needs is empathy . . . truckloads of it.

Vince,i don’t sure if empathy is enough.

People that stutter look different on stuttering than people who don’t stutter.There are some SLPs that get stuttering…. but they achieve it by listening to us the stutterers and understanding that stuttering is different than what they thought.

Unfortunately most SLP’s think they dont need to learn nothing they are already the experts so they never understand stuttering.

Thanks

Ari

geashono@gmail.com

Hi Vince,

I sincerely appreciate this paper. As a grad student of speech language pathology, I am very interested in the topic of stuttering and often associated this subject with “fluency” or “dis-fluency.” It is incredible that your feeling towards “fluency” really opened my mind to see and understand that there is much more to it than this. My professor assigned my class to go into the library and pretend to stutter while conversing with random, unknown people. That experience has left me extremely empathetic to those who stutter. Your confidence is truly inspiring. Again, I really appreciated reading this paper.

Thank you,

Aziza

Aziza,

True story. I was in Reagan National Airport in D.C. about 15 years ago waiting on my flight. The flight was overbooked as usual and their was a long queue at the gate ticket desk. A young man was speaking with the attendant and he was having quite a bit of trouble. It sounded more like aphasic speech than stuttering. I could tell the situation was getting more tense with the people in the back of the line starting to complain. (“Why do people like that try to fly?” “Somebody give him a pen and maybe he can write it.”) I got up from my seat and edged closer, thinking I should try to do something but not exactly sure what. About that time the flight attendant summoned one of her supervisors who took the passenger away from desk and talked to him out of the agitated crowd. I then heard the flight attendant tell one of the most vociferous persons in line that “he only had to deal with a few minutes delay and the young man he was complaining about would likely have to deal with his speech the rest of his life.” I noted her name from her badge. When I got home I wrote Delta Airlines a letter complimenting the way she had handled the situation. Unfortunately, there are two few people in the world like this airline employee. I understand some service corporations and even some police departments are teaching their employees how to handle language difficulties in customers. It’s about time.

Vince-

I just wanted to say that your paper was the first paper I read to start off this year’s online conference, and I could not have picked a better one. I am an SLP graduate student who is currently taking a fluency course. I love what you said about fluency versus finding one’s voice. I agree that the purpose of therapy is not to become a fluent speaker. Yes, that is an important aspect of it, but finding one’s voice is much more important.

One passage that I particularly liked was:

The average speaking rate for those who don’t stutter is calculated to be 167 words a minute while the rate for those who do stutter is 123 words a minute. What happens if you hit 145 words a minute? Are you half fluent?

I think often times we as a field try and put disorders into finite numbers and definitions. Saying that those who stutter use 123 words a minute is a good example of this. I agree with you that fluency is one field that cannot be put into solid, finite definitions.

As a future SLP, this paper speaks to me how individualized therapy is to each person who stutters. Every person is different, not only in their observed stuttering behaviors, but in what they feel underneath. There is no one way to help someone find their voice. The therapist must work to help the person find comfort in their fluency level.

Thank you again for writing this paper. I enjoyed reading it. I am also very interested in reading your book! It sounds extremely interesting and I look forward to reading it in the future.

Thanks- Jamie

Hi, Jamie

You have created a new phrase for me — individualized therapy. That’s the key. One size does not fit all. In fact, one size fits only one when it comes to speech therapy. I hope I’m not getting in trouble with the speech-language professionals and educators. I’m always careful to point out I have no professional training, just personal opinions hammered out from six decades of stuttering. However, I think I will starting adding these initials at the end of my name — Vince Vawter, E.PWS. Expert Person Who Stutters. (Just kidding, Jamie.)

Vince-

I really enjoyed your paper. As a graduate student in the field of speech pathology, I am quite unfamiliar with fluency and the different thoughts of people who stutter. Your thoughts on fluency really made me more open minded on what therapy should really be about. It’s not always about trying to “fix” the stutter, but to help the person feel more confident. Did you ever encoutner any SLP’s who forgot about your voice?

I admire you for being so driven in finding your voice, and I’m happy you’ve come to a place where you’re confident in your speech. I also think it is great that you use humor when speaking to formal crowds!

Thank you for sharing your story.

Morgan McCaslin

Graduate Student

Illinois State University

Hi Morgan,

My last therapy was 25 years ago, and it was a one-size-fits-all approach. Anytime I brought up an emotional aspect connected with my speech, I was told to just concentrate on the mechanics. That was like telling me that the first 35 years of my life were irrelevant.

Hello Vince,

Like so many other who have commented I am an SLP graduate student. My instructor is a PWS, which allows him to provide us a well rounded perspective from both sides of the therapy table. Like you he advocates treating the whole person and not just the disorder/delay. I suspect teachers like mine are leading the way in the change you notice in the treatment of PWS.

While reading your paper, I was struck by a few questions. What do you see as the next evolution in treatment of PWS? Also, do you see a culture, similar to Deaf culture, arising among PWS now that there is an increased connection and move toward acceptance?

Thank you,

Jennifer Castleton

Graduate Student

Idaho State University

Goodness, Jennifer. This is the season for tough questions.

I would like to think that with all the work being done on genetics that a stuttering gene could be clearly identified where pre-vocalization therapy could begin on babies. I may be just dreaming on this one, but I always like to dream. I continue to believe that more breakthroughs will occur when we fully explore the conundrum that “stuttering is what you do when you try not to stutter.”

Your second question may be the more difficult. “Acceptance” is a word surrounded by land mines. How can we separate “acceptance” and “giving up”? We can’t say to an 11-year-old “you will never talk like your friends but we will teach you not to care.” That is a negative approach. The positive approach is “you have a unique voice and we will help you find ways to use it that you never thought possible.”

As long as we are looking to the future, I’m also a little concerned about the effect of social media on PWS. How many of us are using a keyboard when we should be vocalizing our thoughts? I don’t know if it’s a problem or not, but it concerns me. Can we voluntarily stutter when we Tweet? I’m not sure, but I think I might try it.

Hi Vince!

I am a graduate student studying fluency at the moment. I thoroughly enjoyed your paper and am interested in your young adult book. It sounds fascinating! I liked your 3 part stuttering manifesto – fluency is over rated! I do not stutter, but I am not fluent 100% of the time. It shows that I am human, and I like that! When you were younger, how did you feel about your dysfluencies? Also, how did your family and friends react to it? What was your experience at school? Finally, what is your advice you can give us future SLPs to make our fluency clients happy and hopeful? Thank you for your time, and I look forward to your response!

Kelly Highland

CSUF Graduate Student

Hi, Kelly

I spent my teen years never admitting to myself that I was a person who stuttered. I tried to hide it in every way imaginable. Much of this is detailed in my book. Friends and family never talked about my speech. It truly was the elephant in the room. Keep in mind, this is in the late 50s and 60s. School was survival at best. I tried to find my self-worth in sports at the expense of work in the classroom. I have had some one-on-one discussions with PWS (always careful to point out I have no professional training), and I usually begin by saying that in all likelihood you will figure out your voice for yourself. I tell them because you and you speech are unique, your answer will be unique. I say that your SLP will be there to guide you, but ultimately you need to find your own path to your voice. Your first task is confrontation with yourself. Only then can your true voice emerge. I always end by quoting that great philosopher Mick Jagger: “You can’t always get what you want, but if you try some time, you just might find, you get what you need.”

Hi Vince!

I really enjoyed your paper and hearing about your story. I am a graduate student pursing my masters in Speech Pathology and also a person who stutters. I found it really interesting how you defined “finding ones voice” and how you found your voice however you did not find fluency. The analogy that you made about the swimming duck was right on point. I often find myself speaking “fluently” however it may be such a struggle to do so that I sometimes wish I just let my stutter out. You seem to be at a point in your life where you are very comfortable with your speech and the fact that “found your voice” attests to it.

Did you always have such a positive outlook in regards to your stutter? If not, what sparked the change?

You said that you were a veteran of speech therapy, what techniques and approaches in therapy, as either a child or adult, do you feel worked best for you?

You mentioned that you often substitute words and sounds in daily conversations. Do you ever feel like although you are perceptually fluent when doing so, you would rather just say exactly what you want at that moment and stutter along the way?

Thank you for sharing your journey through stuttering as well as your stuttering manifesto that you developed through determination and contentment.

Samantha

My positive outlook didn’t come until I was in my 30s. I guess what sparked the change was a desire to make sure I could provide for my family. In other words, I didn’t have the courage to change my way of thinking about my speech just for myself.

My two attempts at therapy with a SLP were in the 50s and 60s. They weren’t effective because I didn’t give them a chance. I would not admit I was a PWS. I know that sounds implausible, but that’s what I did. I only tried to hide. After that I tried electronic maskers, forms of psycho-therapy, delay-auditory feedback and then precision fluency shaping. All worked to some extent, but it was fleeting success. It’s then that I stopped chasing fluency and just started listening to and being true to my voice. I know those words ring hollow with anyone who has not gone through the trauma of stuttering, but it is very real for me. I tried to express that breakthrough in my book. Occasionally, I do get tired of substituting words and will voice some do-or-die stutters. And just so I don’t get too contented with my voice, I will do some voluntary stuttering just for the heck of it. All of that mish-mash is my voice. It’s like no other. It serves me well. I have no complaints.

Hi, Vince:

I read your article and I find it remarkable. I very much appreciate your sense of humor. I am pursuing my graduate studies on Speech Language Pathology and I’m currently on the second year.

I have a question regarding something you mention in your article and that is that you do not do therapeutic voluntary stuttering. Why is that?

I did voluntary stuttering for a while, but I realized that it caused me to “think” about my speech. I choose not to think about my speech now. I just speak. If a stutter or a block happen to appear, I move on and take no notice of it. When I started public speaking, I would give myself “grades” on how I did. Now, I don’t bother with that. I know what I want to say and say it. Since stuttering is what you do when you try not to stutter, I don’t try not to stutter. I realize the concept seems vague, but when I was explaining it to a friend who has a doctorate in philosophy, he informed me that zen philosophy is based on that very concept. I would never say that therapeutic voluntary stuttering is not effective. It’s just not for me at this time. That brings up another point. As soon as a PWS settles on a “path” to his/her voice, that person should take that path but then be ready to reassess and take a slightly different path if the need is felt. I’ve learned that stuttering is not static. If X happens then Y does not always happen. Putting it another way, find your path but be ready to change paths to stay on course.

Mr Vawter –

Thank you for your wonderful paper. Your message is so positive and practical. I am a student in speech-language pathology and your manifesto and analogies are ideas that I will definitely keep in mind as I embark into the therapeutic process.

In my fluency class, I will be giving a presentation about the nature of anxiety/fear that often lies under the surface for PWS. I was wondering if you could elaborate on your allegory of the swimming duck – “I may seem calm on top, but I’m paddling like crazy below the surface.” Can you explain more about what’s happening below the surface for you? After reading your paper, it sounds like you are someone who has reached a calm place both above and beneath the surface.

Thank you,

Zisel

Hi Zisel,

A good question, and I’ve spent some time thinking about the answer. Assessing my state of mind before I found my voice and after, it seems to me I have replaced fear with adrenaline when it comes to public speaking. Some might say I am “performing” when speaking in a formal situation. I think it’s more than that.

In my early 30s I could not imagine myself giving a speech in a formal setting. Now, when giving a reading of my book or speaking at a lectern, it seems whatever drives my voice becomes hyper-focused. I feel an energy kick in that is not a nervous energy but almost an energy in my core. If I read from my book, the words on the page seem bright and clear. If I’m giving a speech (I never use notes), I scan the room and look directly into the eyes of the those in the audience.The longer I read or speak, the more the energy is released. Is this sounding a little whacko?

I’m tempted to say the paddling-like-a-duck analogy comes from an over abundance of word substitutions, but, of course, I can’t substitute words if I’m reading.

I guess I really can’t explain it. I just feel an inner power when I hear my voice that was silent for so long.

Could it be I’m 67 and I just don’t give a flying-flip anymore? Possibly.

Sorry to be of so little help, but sometimes that happens with honesty.

Hi Vincent,

Thank you for sharing your personal views on stuttering. As a current graduate student in an SLP program, I would have to agree with you. Many programs are shifting from focusing solely on fluency to focusing on helping the person who stutters find a voice in which he or she is comfortable, including the course I am currently taking. Fluency is different for everyone person and difficult to define because of this, and therefore a hard to reach goal. The “average” speaker is rarely fluency all the time. Unfortunately, I have to report that not every college program is making this ever-important shift. My undergraduate program, for example, focused more on the etiologies and demographics of stuttering rather than treatment of any form. Despite this, it was clear the professor believed achieving fluency should be the ultimate goal of therapy. I have learned more in my current class about stuttering in the first seven weeks than I did from the semester of my previous class. I feel that working on the emotional aspects of stuttering is just as important (if not more so) than attaining fluency. Fluent speech should not be the end goal of therapy, but rather the goal should be speaking more comfortably. Thank you again for sharing. It was very enlightening!

Justine

Hi, Justine

From where I stand, you certainly seem on the right path. I wish I could better put into words what “finding my voice” actually means. When I talk to young PWS, I’m almost afraid to bring up the subject because it appears I’m talking about just “giving up” when it’s actually just the opposite. I rewrote the last chapter of my book no less than 50 times trying to explain the phenomenon. I’m still not sure it’s adequate, but it’s as close as I could come.

Vince,

Thank you for sharing your experience. I am a speech-language pathology graduate student at ISU. It is refreshing to hear your experience. I walked into my first fluency class expecting to learn how to “fix” stuttering, only to learn that there is no guarantee of a fix. We all communicate in our own individual way. I learn so much from experiences like yours. As professionals we want to help, but we need to keep in mind that helping our clients find their voice may be the most beneficial thing we can do. I am curious how we can help parents and clients recognize the PWS as a unique, valuable, intelligent person even when the stuttering persists? Is that something they must find on their own?

Hi JT Young,

I don’t want to sound facetious, but the first thing you might have parents do is read “Paperboy.” It’s about a boy who finds his voice, not necessarily fluency. Seriously, one of the reasons I wrote my book is to explore this very question. It’s not an easy concept to master it took me about 50 years, but there’s no reason it must take that long. Good luck.

Mr. Vawter,

I am a graduate student studying to become a speech language pathologist. I agree with your statement that there has been a “critical change” within the stuttering community in regards to therapy objectives. I am, at the moment, enrolled in a graduate course that is focusing on stuttering and other fluency disorders. My professor has spent the majority of the 8 weeks of the semester discussing the importance of assisting individual’s who stutter with techniques to help them “find their voice.” My professor is extremely passionate about his distaste for the role fluency has played in stuttering therapy. Why has there been such a push for individuals who stutter to achieve fluency instead of focusing on the intrinsic struggles that affect the individual’s want to share information? Fluency is an impossible objective, not even “fluent” speakers are fluent. I look forward to some day assisting an individual create realistic and achievable goals that will allow them to find their voice!

Thank you,

Anna S.

University of Wisconsin Stevens Point

Well stated, Anna. I would say your goals are right on target.

Dear Vince,

Thank you for sharing your journey. I am a second year Speech-Language Pathology graduate student. I found your responses to be as valuable as your paper. I work in a remote community that does not have access to services and the few people that stutter generally do not speak. I could not agree with you more that finding your own voice is imperative.

You mentioned that you became more confident in your 20’s when you started a family. You also mentioned that the goal of therapy for the longest time was fluency and did not address the emotional aspects. How/when did you address the emotional aspects? Your statement, “My only regret on my long journey is that I courted that fickle mistress called fluency for too long instead of simply searching for a voice with which I was comfortable. If fluency sounds unnatural, it doesn’t work”, resonated with me. Did you find therapy enjoyable or did you see it as just something you had to do?

Thanks,

Eileen

Idaho State University Graduate Student

Hi Eileen,

All good questions. When I was in my teens, I struggled in therapy mightily because I continued to try to hide my stutter. If you can’t even admit you stutter, therapy doesn’t do much good. In my 30s I wanted to improve my marketplace skills so I went through an intensive (and expensive) fluency-shaping program. Even while I was there and often-times clinically fluent, I knew in my heart that it wouldn’t transfer outside the program. I was right. My so-called fluency lasted about 30 minutes in the real world. At that point in my mid-30s I knew I would have to figure it out for myself. About the age of 50 I realized I had indeed found my voice. I never looked back. I contend that if the PWS is not treated holistically, any fluency gained will be a false fluency. The SLP is there to help the individual find his/her voice. It can’t be done alone. It’s hard work. Good luck.

Dear Mr. Vawter,

I am currently pursuing my Masters in Speech-Language Pathology. I also currently work as a Speech-Therapy Assistant with preschool-aged children.

I enjoyed reading your paper – your duck analogy provided a very clear picture to me of the struggles that people who stutter undergo when attempting to achieve fluency.

I also liked your comment regarding “finding your voice” versus finding fluency. It is definitely a different way to think about setting therapy goals – and emphasizes (to me at least) the importance of actively involving the client during selection of therapy goals/outcomes.

Looking back, would you change any of the therapies or strategies you were taught? Did any of them aid you better with “finding your voice”?

Thank you again for sharing your story. I look forward to reading your book!

Premila

Idaho State University Graduate Student

Hi Premila,

I have two regrets concerning therapy.

1. I refused to give early therapy a chance because I was “hiding” my stutter.

2. The goal determined for me in my fluency shaping protocol was 100% clinical fluency. I should have been mature enough to see that finding my voice was more important than fluency.

Having shared my regrets, I look forward to say that finding one’s voice is always a blessing, whether or not it comes early or late in one’s life.